13 December 2010

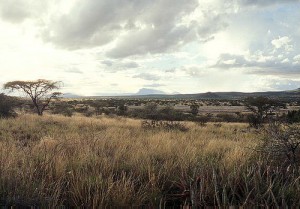

Why did northeast Africa become dry 2 million years ago?

Posted by mohi

What led to the expansion of grasslands in northeast Africa around 2 million years ago? In PP12B-07 “Why did Africa became dry in the mid-Pliocene?,” Peter deMenocal of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory presented a new hypothesis suggesting that the emergence of changes in sea surface temperature in the Pacific and Indian oceans resulted in a decrease in precipitation in northeast Africa.

Part of deMenocal’s interest in ancient climates of Africa involves the connection between climate change and human evolution. Fossils of Homo erectus from this region, approximately 1.8 to 2 million years old, are the earliest instances of any member of a human lineage being found in an open, arid environment. Fossil and other evidence from this era indicate a dramatic burst of grass populations and an increase in the proportion of grazing animals.

So what caused North Africa to transition from a more wooded and verdant environment to dry grassland? Previous hypotheses, including some from deMenocal himself, have looked at cooler surface sea temperatures in the North Atlantic, reduced global carbon dioxide levels, or uplift of land in eastern Africa. But differences between northwest and northeast Africa, such as northwest Africa’s earlier transition to aridity, had always bothered deMenocal. Whereas the spread of arid land in northwest Africa about 3 million years ago can be explained by cooling of the North Atlantic and precipitous sea surface temperature increases moving from north to south, these changes only account for a modest change in precipitation in northeast Africa.

deMenocal and his team looked at temperature records from the east and west sides of the tropical Indian and Pacific basins over the last 5 million years. They found that an episode of cooling off the Arabian Peninsula and warming off the northwest coast of Australia coincided with the transition to open grassland in northeast Africa. Since then, sea-surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean have experienced shifting conditions, oscillating between temperatures in the west being cooler and warmer than temperatures in the east. Their discovery that the onset of this oscillation coincided with less rain in East Africa fits with models of past climate and with findings that modern rainfall variability in East Africa is largely determined by temperatures shifts in the Indian Ocean.

–Susan Young is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.