23 September 2016

Ms. Callaghan’s Classroom: The Underwater Flying Glider

Posted by larryohanlon

This is the latest in a series of dispatches from scientists and education officers aboard the National Science Foundation’s R/V Sikuliaq. Jil Callaghan is a 6th grade science teacher at Houck Middle School in Salem, Oregon. She is posting blogs for her students while aboard the Sikuliaq as part of a teacher at sea program through Oregon State University. Read more posts here. Track the Sikuliaq’s progress here.

By Jil Callaghan

Dated: 22 September 2016

Earlier this week we deployed a glider that belongs to the University of Alaska at Fairbanks (UAF). What’s a glider? It is an underwater robot that “flies” around the sea going from the surface to the bottom of the seafloor collecting different types of science data.

Brita Irving is a research scientist with the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. This is one of 6 underwater electric gliders that she oversees.

The crew uses a crane to lower a small boat over the side of the ship to deploy the glider away from the ship.

While the crane holds the small boat above the water and level with the deck of the ship, the glider is rolled onto the small boat.

The small boat will go about 100 meters away from the ship before they put the glider in the water. This ensures that the glider won’t run into the ship.

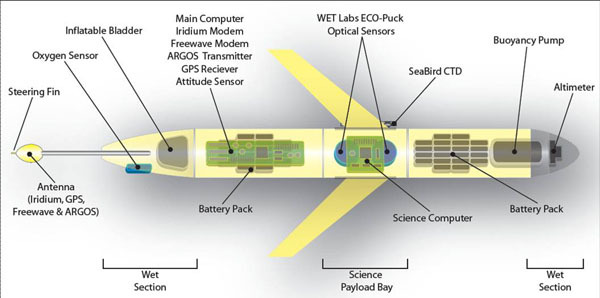

The glider does not have a propeller or motor to push it through the water, instead it uses buoyancy and a 10 kg weight. Brita adds or subtracts weights (based on the density of the water) to make it neutrally buoyant so that it floats at the surface. When it needs to dive, the glider moves the weight forward, which changes its center of gravity, and makes the nose of the glider point downward. The weight is moved backward or forward by a screw; it slides along as the screw rotates.

In the nose cone, it has a diaphragm – a plate that moves to allow water in or push it out. When it allows more water in, the glider becomes negatively buoyant and starts to sink until it reaches the depth that Brita told it to go to. When the glider needs to go back to the surface, it does the reverse; the diaphragm pushes water out, the weight moves back, making the nose of the glider point upwards.

From the bridge of the ship Brita “pilots” the glider using computer programming to communicate with the glider, sending and receiving files. Mission files that Brita writes tell the glider how quickly to dive, how deep to go, how often to sample from its different sensors, give it waypoints (tell it where to go), and run diagnostic checks.

If it didn’t have wings, the glider would just sink through the water column, but the wings create buoyant forces, like the lift under airplane wings, that allow it to glide through the water.

The plan is for the glider to “fly” around the ocean for 5 days before we come back and pick it up again.

The glider can run on its batteries for up to 3 months, and all you have to do is pay for the upload of data via satellite, which is about $200/day, vs. $50,000 a day for a research ship the size of the Sikuliaq. “It surfaces approximately every 2 hours and sends us snippets of data over satellite so we can see how the gilder’s doing. It sends small subsets of data – the full set of data we get when we physically collect the glider,” says Brita.

You can put whatever instruments you want on top of a glider. One of the UAF gliders has a hydrophone to listen to the sounds that marine mammals are making.

This glider is measuring salinity (how salty it is), temperature, it has a couple of pressure sensors so it can tell how deep it is, a fluorometer, which is an optical instrument which measures chlorophyll (what phytoplankton and plants use to take light and CO2 to make their own food), CDOM (Colored Dissolved Organic Matter), and back scatter (how much stuff is in the water that blocks the light). It also measures pC02, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (how much carbon is available to the organisms in the ocean).

Watching the glider deployment from the bridge. Brita ran the glider through 2 test runs of diving and resurfacing to make sure that everything was working correctly.

The crew that made the glider deployment possible. From left to right: Jim, Paul, Ethan, John, Artie, Elliot, and Eric.

Unfortunately, after only one day in the water, the glider had part of its electronics flood with water. The glider is part of UAFs research and development, and with research and development there are always failures that drive the next improvements and advances. Such is science!

This post was originally published on thedynamicarctic.wordpress.com

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.