13 September 2018

The Blob hides in the deep

Posted by kcawdrey

Oceanographic monitoring finds marine heatwaves have lasting effects on BC Central Coast fjords and may play a role in a disappearing fishery.

By Jonathan Kellogg

Fall is nearly here and, for most of us, that means the end of the summer heatwave. In the waters of British Columbia, however, the seasonal cycle is stuck. A marine heatwave began more than four years ago and new research suggests it won’t be disappearing anytime soon.

Marine heatwaves are not new. But heatwaves are getting more intense and more frequent with a changing climate. Over the fall and winter of 2013 and 2014, satellites detected above normal temperatures in the surface waters of the northeast Pacific. At its peak, the mass of warm water—nicknamed “The Blob”—had water temperatures up to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than normal and covered an area larger than Australia.

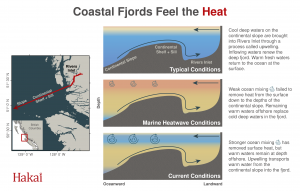

Scientists repeatedly thought the marine heatwave was abating when satellite observations of sea surface temperatures moderated after winter storms. But satellites cannot measure temperatures below the surface.

“[The new] work highlights that you cannot effectively monitor the ocean with just satellites,” says Jennifer Jackson, an oceanographer with the Hakai Institute.

Jackson and colleagues showed what satellites missed—that substantial heat remains at depth.

Jackson and colleagues Greg Johnson (NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Lab), Hayley Dosser (University of British Columbia), and Tetjana Ross (Fisheries and Oceans Canada) combined four separate time series from oceanographic monitoring programs along the coast of British Columbia. The collaborative group noticed strong similarities between data sets from the open ocean and the coastal fjords of British Columbia.

“By combining diverse data sets you are able to describe the progression of this subsurface warmth from the ocean onto the coast and into the fjord,” says Johnson. “I think that’s pretty cool.”

Recently accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, the time series from Rivers Inlet and the northern end of Vancouver Island dates back 15 to 20 years and closely matches those data from Line P, a time series in the central northeast Pacific dating back to 1956. All together, there is compelling evidence that heatwaves have occurred on this coast before and may have contributed to ecological shifts in the past.

“Without observation programs like Hakai, Argo, and Line P we wouldn’t be able to see these dramatic shifts,” says Jackson. “It’s a bit alarming in the context of the whole time series.”

This work may be a significant piece to a lasting puzzle in Rivers Inlet, a 45-kilometer-long fjord on the Central Coast of British Columbia. Historically one of the most productive sockeye salmon fisheries on Canada’s west coast, the catch declined in the late 1970s and regulations didn’t help reverse the trend. By the early 1990s the fishery was closed and over 20 years later questions remain.

“There’s now a lot of evidence supporting salmon’s dietary shift during these warm periods,” says Jackson.

The juvenile salmon diet is largely made up of copepods. But, not all copepods, a type of zooplankton about the size of a grain of rice, are created equal. Warmer waters are preferred by a species of copepod that is not as rich in nutrients and fats that the young salmon need. This “junk food” diet likely leads to increased juvenile salmon mortality as they make their way to the ocean.

Mounting data suggests that warm anomalies contributed to the fishery collapse through these food web effects. Heatwave events occurred following the major El Niños in the early 1980s and the late 1990s, around the times that regulators significantly reduced the catch and closed the fishery.

Scientists are hoping strong storms this winter will bring back the nutrient-rich cool waters of the northeast Pacific. Those conditions may be key to helping the fishery of Rivers Inlet rebound in the coming years. Regardless, ongoing monitoring will continue to teach us about the past to make well-informed decisions for the future.

–Jonathan Kellogg is a science communications coordinator at the Hakai Institute. This post originally appeared as a blog post on the Hakai Institute website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.