10 March 2020

Major Greenland glacier collapse 90 years ago linked to climate change

Posted by larryohanlon

By Larry O’Hanlon

Ninety years ago there were no satellites to detect changes in Greenland’s coastal glaciers, but a new study combining historical photos with evidence from ocean sediments suggests climate change was already at work in the 1930s and led to a major collapse of the one of Greenland’s largest coastal glaciers.

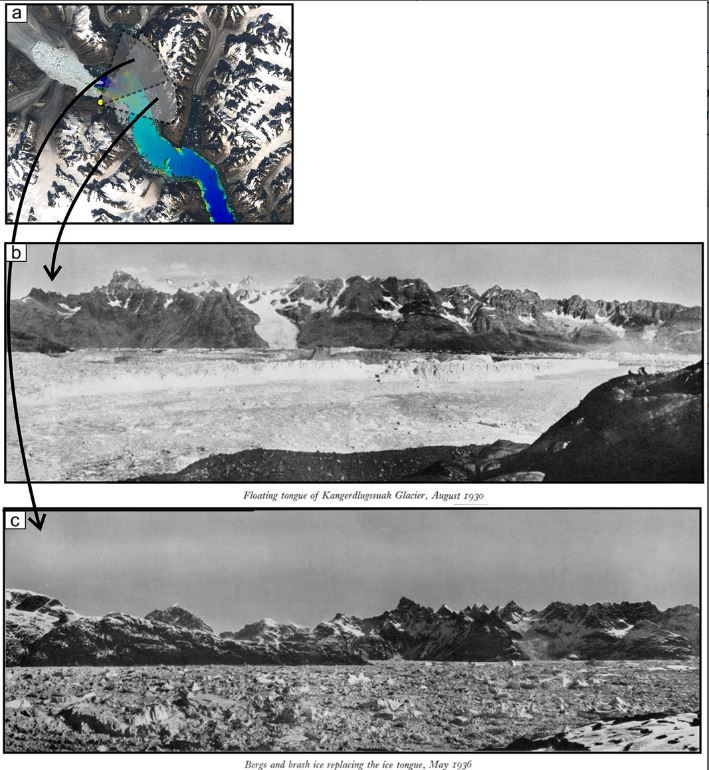

The only reason scientists today know about the Kangerlussuaq Glacier’s dramatic retreat in the 1930s is the existence of both aerial and ground-level photos taken by explorers before and after the glacier’s tongue had dislodged itself from a submarine ridge. The ridge had pinned the glacier in place, perhaps making the glacier relatively more stable than many other coastal Greenland glaciers.

“We found out about the collapse by looking at old pictures,” said geologist Flor Vermassen of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. “And this matched our findings from the sediments.” Vermassen is the lead author of a new paper describing the Kangerlussuaq collapse in the AGU journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Photographic evidence of a major change in Kangerlussuaq presented in a 1937 paper by Wager et al. a) The yellow dot is the position where the land‐based photographs were taken in 1930 and 1936. The direction and fields of view for the images are indicated by the gray triangles. Note that the photo from 1936 was aimed in a slightly more northern direction. b) Photograph of the floating ice tongue in August 1930. c) Photograph of the ice mélange in May 1936.

The historical aerial and ground-level photos were from Danish and British expeditions that set out to Greenland’s east coast from 1930 through 1935. The photos show a dramatic retreat of the glacier following a well-documented period of air and water warming in the 1920s, Vermassen explained.

To confirm the timing of the Kangerlussuaq collapse and the changing water temperatures, Vermassen and his colleagues analyzed sediment cores collected from the seafloor in front of the glacier. They found chemical and physical evidence that confirmed the warming, including a layer of debris that marked the melting of ice and the fall of ice-rafted debris onto the sea floor.

Surprisingly, the collapse of Kangerlussuaq stands out among Greenland glaciers not because it is early, but because it is late. The year 1900 has been used by researchers as a Greenland‐wide point in time when glaciers started to retreat, Vermassen and his colleagues write. It was the pinning of this glacier against a large submarine ridge that might have kept Kangerlussuaq stable for years longer.

“It’s a rare thing to be able to show such a big event before the satellite era.” Vermassen said. “It fits in the general decrease in ice in the 20th century.”

Larry O’Hanlon is a freelance science writer and manager of AGU’s blogosphere

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

As a member of the University of Oregon Research Group working on the Skaergaard intrusion in East Greenland (1974, ’76, 79, and ’82), I was most interested in the article by Larry O’Hanlon just reviewed by AGU. Glad to see that the GGU (Greenland Geological Survey) is still involved in geological research in this area. I am sure you have already heard from my friends Kent Brooks (formerly with University of Copenhagen) and Troels Nielsen ( GGU, retired?). Wager, of course, was a geological icon of igneous petrology and field studies in East Greenland. The area has a history rich in the understanding of igneous petrology established by Wager and others. Thanx!

Dear mr. Allan Kays, I am delighted to read your response! Yes during my work at GGU (now called ‘GEUS’) I became acquainted with Troels Nielsen, a very kind man indeed :). It has been a privilege to be able to make use of the work of the great early explorers such as Wager, Koch etc..

Kind regards,

Flor