7 July 2017

Greenland’s summer ocean bloom likely fueled by iron

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

Iron-rich meltwater from Greenland’s glaciers are helping fuel a summer bloom of phytoplankton

By Ker Than

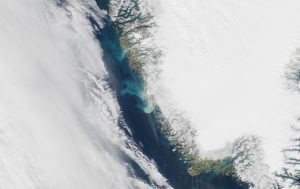

Satellite photo of glacial meltwater runoff from the Greenland Ice Sheet. A new study finds iron particles washed off Greenland’s rocks and soil and ferried into the sea by the meltwater are driving a recently-discovered summer algal bloom.

Credit: NASA.

Iron particles catching a ride on glacial meltwater washed out to sea by drifting currents is likely fueling a recently discovered summer algal bloom off the southern coast of Greenland, a new study finds.

Microalgae, also known as phytoplankton, are plant-like, marine microorganisms that form the base of the food web in many parts of the ocean. “Phytoplankton serve as food for all of the fish and animals that live there. Everything that eats is eating them ultimately,” said Kevin Arrigo, a biological oceanographer at Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences in Stanford, California.

Greenland’s summer phytoplankton bloom had gone largely unnoticed until just recently, despite the fact that it blankets 200,000 square miles and turns the waters of much of the Labrador Sea turquoise. “It’s one of those places where people just don’t sample very much,” Arrigo said. “We have satellite images of this region going back years, but almost nobody’s looked at this particular spot during the summer.”

After learning about the summer bloom a few years ago, Arrigo and his team set out to discover what might be fueling it. Marine biologists have long known that the primary driver of Greenland’s spring bloom is sunlight. In high-latitude regions where the temperature plummets in winter, the ocean’s water column gets mixed as cooling surface water sinks to the seafloor and benthic nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron are dredged to the top. “When spring arrives, then you’ve got sunlight and nutrients — the two ingredients you need for a bloom to occur,” Arrigo said.

However, this explanation doesn’t account for the summer bloom. After all, by the time summer arrives in Greenland, sunlight has been plentiful for several months already, and the recently mixed water column is still rich in most nutrients.

To solve the mystery of what might be driving the summer bloom, Arrigo and his colleagues compared NASA satellite imagery of the summer bloom and results from computer models simulating Greenland’s glacier melt and ocean currents. The team found a significant correlation between the outflow of freshwater from Greenland’s melting glaciers and the timing of the bloom.

“The summer bloom develops about a week after the arrival of glacial meltwater in early July and persists until the input of glacial meltwater slows in August or September,” said Gert van Dijken, an ocean biogeochemist at Stanford and co-author of the new study.

In a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, the scientists hypothesize that it’s not the influx of the meltwater itself that is triggering the summer bloom, but rather iron particles washed off from Greenland’s rocks and soil and ferried into the sea by the meltwater.

“The waters around Greenland happen to be one of the rare iron-limited places on Earth,” said Arrigo, who led the new study. “A lot of the photosynthetic machinery of phytoplankton requires iron. If they don’t have iron, they can’t capture light and make food.”

The summer meltwater influx is likely refreshing the iron supply in the Labrador Sea around Greenland after its been depleted by the spring bloom. “All the pieces fit together,” Arrigo said. “The fact that when the runoff comes, the bloom starts. The runoff likely carries lots of iron with it.”

If iron-rich meltwater is indeed what’s spurring the summer bloom, then the region’s biological productivity could rise in the decades to come as climate change causes Greenland’s glaciers to melt earlier in the year. “It may be that a much larger fraction of the northern Labrador Sea could become a lot more productive in the summer than it’s been,” Arrigo said.

The scientists have already submitted grant proposals to the National Science Foundation to fund a summer research cruise to Greenland to test their hypothesis.

“We want to go there before the summer bloom starts to measure the concentration of nutrients, especially iron,” Van Dijken said, “and then make the same measurements after the glacial meltwater arrives and the blooms start.”

— Ker Than is the Associate Director of Communications at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. This post originally appeared as a news story on Stanford’s website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.