9 March 2011

Spotting A Tornado On Your iPhone-Part Two

Posted by Dan Satterfield

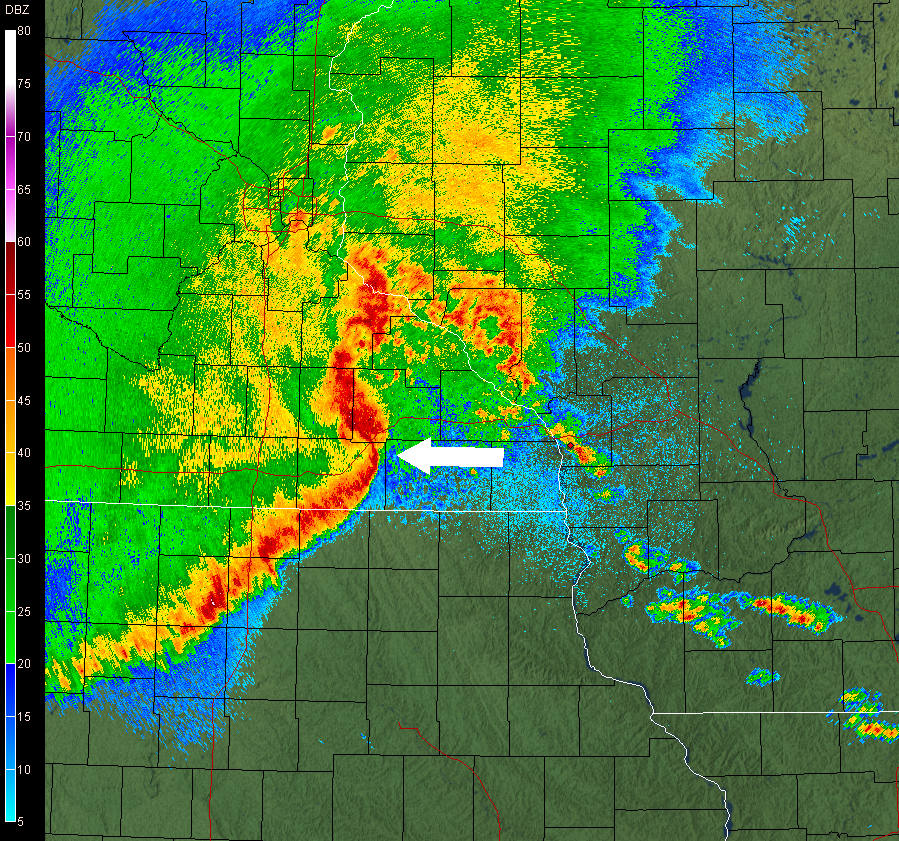

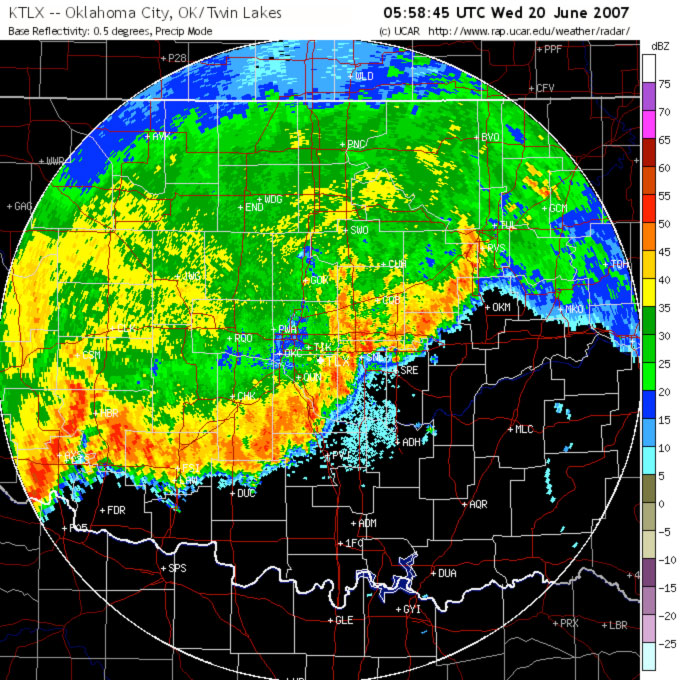

So what do you think? Is this a band of severe storms? For the most part they are just heavy, but there may be some strong winds in the line. Large tornadoes rarely come out of a line of storms like this. Heavy rain and gusty winds are the main threat.

In part one, I discussed using the Radar Scope app to tell if you are in the path of some really mean weather. In this post are some examples of dangerous weather. The main thing to look for are bow echoes and hook echoes. I’m just scratching the surface of radar meteorology here, and the Radar Scope app will light up a red box if a tornado or severe thunderstorm warning is issued.

No matter what you think you see, take that warning seriously!

You’ve probably heard of a “hook echo” on radar before, and they are the time tested way that tornadoes are spotted on radar. Hook echoes are still watched for, but now Doppler radar allows us to see the winds inside the storm, not just the shape of the echo. Remember the Doppler dilemma I mentioned in part one? This limits the ability to look at winds at great distances, so the old hook echo is still very much used!

The closer the storm is to the radar, the closer to the ground we can see. For tornadoes (and straight line winds), this is critical. Doppler radar cannot see all of the winds, just the component of wind that is going toward or away from the radar. To make that clear, a 100 mph wind blowing from left to right, perpendicular to the radar beam will show zero velocity! We can infer a rotation from the data we have and that is how it’s done.

So below are a series of images of things to watch out for. The more it looks like one if my examples, the more likely it really is one!

Notice the big bow in this squall line? It's called a bow echo and the white arrow is pointing to the area that is likely going to get very high winds. This is an extreme case and if you see this approaching your location, very high winds are likely.

A non-severe squall line. No bow echoes and a broad heavy rain line with no intense rain (red color) showing.

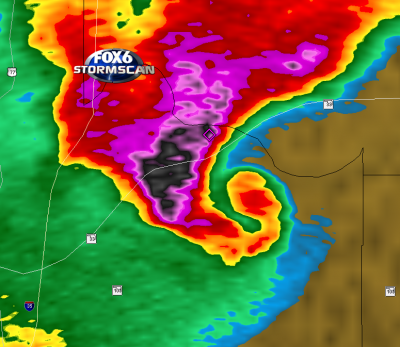

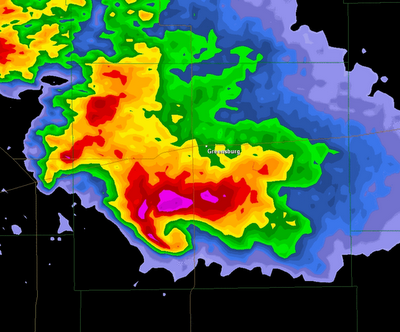

A classic hook echo. If you see this on your iPhone, head to to the sturdiest building you can find (run, don't walk!). A large and possibly violent tornado is likely being produced. If in a car and you can drive at a right angle to the storm then do so. Don't try it in a city; tornadoes do not stop for stop lights and traffic jams.

The tornado will be at the bottom right of the echo here and probably at the northern edge of the appendage. Why tornadic circulations can cause a hook echo to form is the subject of a future post. You’ll almost certainly see a cell like this by itself or ahead of a squall line. Super-cells like this rarely develop without a tornado watch being in effect. If you see this on your iPhone while under a tornado watch, it’s going to be a mean night.

Storm Relative Velocity (SRV) image of the Greensburg, KS tornado. The tornado here wiped out almost the entire town. See below for an explanation of what you are seeing. Images from NOAA unless otherwise noted.

The radar product above is called storm relative velocity. It shows the wind in the storm as if you were moving along with it. The dark blue pixels are very high winds blowing toward the radar. Right next to this is bright pink, indicating very high winds blowing away from the radar.

In other words, there is a violent rotation here. This radar signature leaves little doubt that a tornado is either forming or already on the ground. It’s extremely unlikely you will see this with no warning in effect. The weather-geek name for this is a TVS–Tornado Vortex Signature.

Now, some examples of strong straight line winds. The images below are from upstate New York as a rapidly moving squall line called a derecho (dah-ray-show) event moved through. Notice the bow echoes in the reflectivity and the base velocity image showing high winds approaching the radar.

Image from NOAA-NWS. The curved blue echo at the bottom that looks like a donut was caused by the very strong winds.

The last thing to show is something that’s a rather rare radar signature. If you see it, the storm is almost certainly producing very large hail. I’m talking bigger than golf balls and maybe softball size!

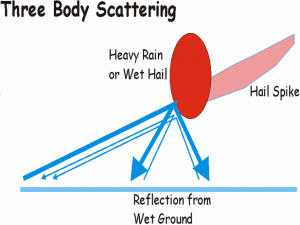

Its called a three body scatter spike (TBSS) and it happens when the radar beam hits ice with a coating of water on it. Ice surrounded by water will reflect the radar beam very well, and some of the beam will be reflected to the wet ground below–then back to the ice chunk, and back to the radar.

The radar cannot show the change in direction, and it will show a spike extending behind the cell. I’ve only seen a three body scatter spike during a severe weather event a couple of times and both instances had numerous reports of up to baseball size hail.

Hopefully you have an idea of what to look for if you buy the app. There is a lot more to it, but perhaps you can see why severe weather now-casting is so fascinating!

The three body scatter spike extends behind the echo(pointing toward bottom of the image) on the opposite side from the radar.

Dan Satterfield has worked as an on air meteorologist for 32 years in Oklahoma, Florida and Alabama. Forecasting weather is Dan's job, but all of Earth Science is his passion. This journal is where Dan writes about things he has too little time for on air. Dan blogs about peer-reviewed Earth science for Junior High level audiences and up.

Dan Satterfield has worked as an on air meteorologist for 32 years in Oklahoma, Florida and Alabama. Forecasting weather is Dan's job, but all of Earth Science is his passion. This journal is where Dan writes about things he has too little time for on air. Dan blogs about peer-reviewed Earth science for Junior High level audiences and up.

Interesting. This would work out so much better if most apps had legends. Then you can tell actual wind speed values for straight-line winds (and direction for those less used to looking at velocity data!) and reflectivity values. Color tables vary so much from app to app (even website to website).

The Radar Scope app does have a legend. tap on the color bar and it will show you the associated reflectivity in dbz or wind velocity for the velocity products. Negative numbers are toward the radar.

Dan

Yahoo weather has a legend on the App Store. And it’s free!!

Great post. I installed Radar Scope the other day and it is an amazing app.

Thank you Dan, this was a great article, I just bought this app last week and am obsessed with weather and am trying to learn how to navigate this app. You helped out significantly. I also heard using correlation coefficient is effective for locating debris balls? Is the tornado always at the end of the hook on the hook echo??

Sorry, I could sit here and ask you a million questions.

Lastly, when looking at Velocity/SuperRes Velocity and it shows white or bright green, thats around 60mph..is that wind shear? It’s confusing a bit because I don’t know how high up that wind is recording so if it’s 1000m lets say and it’s showing white (60mph) does that mean you assume its higher or lower on the ground??

Yes indeed the CC is turning into a dual pole success story. I did a separate blog post on it recently.

Thank you so much for this article! I don’t want to chase storms, I want to avoid them, often we lose Television when it is cloudy, I have purchased these Radar Apps to be able to better see what might be coming.