21 November 2013

Automation, Weather Warnings, and Social Media

Posted by Dan Satterfield

There seems to be a lot of room for improvement when it comes to social media and severe weather alerts.

This is a guest post from The Digital Meteorologist by Nate Johnson at WRAL-TV at Raleigh in North Carolina. It brings up just one of the multitude of issues that forecasters face as we move into a world where social media is a prime source of news information.

As Twitter, Facebook, and other social media began to take hold in weather centers and news rooms across the country a few years ago, one of the earliest conversations was about whether and to what extent automation should play a role in sharing weather information, especially during severe weather situations. This is a bigger deal than it appears at first glance: The interactions between the immediate, reliable, and consistent provision of warning information and the trust relationships between communicators and those in the danger zone are complex and not as well-understood as we would like.

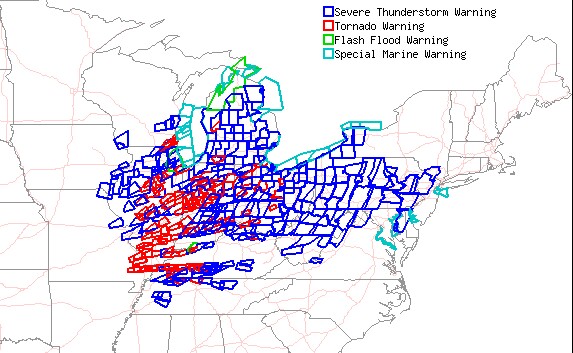

Before I go further, I want to be very clear about my purpose here: I am not writing to criticize folks who are trying to get critical information out to people in harm’s way, often doing so as early adopters with few resources and little backing. However, in watching Sunday’s tornado outbreak unfold in the midwest primarily via radar and Twitter, I was struck by how poorly some automated social media updates come across. More importantly, there’s a flaw in the system that could leave some social media users to believe they’re not in harm’s way when they actually are. I show numerous examples, and where I’ve been critical, I’ve taken steps to anonymize the source. My goal here isn’t to call anyone to the carpet but to raise an important issue in communicating severe weather information.

To Be or Not To Be (Automated)

When it comes to automating weather warning information on social media, there appear to be two camps. Some folks, like social media juggernaut James Spann, prefer typing out warnings on Twitter, saying that it allows him to communicate the warning in his own voice. Others argue automation has a role to play for at least two reasons: Getting the word out as soon as possible and backstopping a meteorologist in providing critical information across multiple platforms when they might be too busy to tweet in a timely fashion (never mind when someone may be away from social media entirely). Even Spann uses some automation – warnings are automated to his Facebook fan page, but he’s on record as saying Facebook is terrible for severe weather updates, and he’s got a point – but that’s another post.

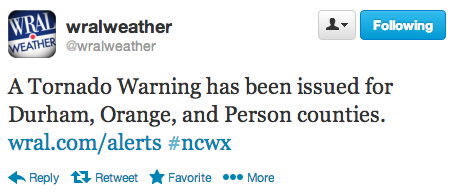

Warning tweet from @wralweather

Personally, I am squarely in the automation camp, but if and only if it is done properly. My definition of “properly” here is a blend of good emergency radio communication (in an emergency, “where” and “what” come first, everything else secondary – if that’s all you’re able to get out, crews can still get to you) and something akin to the Turing Test. To be most effective, severe weather updates need to be immediate, relevant, and readable – and they need to stand on their own. We can’t count on people being both willing (Twitter’s click-through rate is south of 6%) and able (device limits, bandwidth, etc.) to click the link.

When I worked with our tech team at WRAL to automate warnings to the station’s @wralweather account on Twitter almost five years ago, we took the warning feed, created a bare-bones format that allows us the most characters for the important information (“where” and “what”), and had the program write tweets that read like a human typed them.¹ I and other meteorologists and reporters supplement the automated tweets with additional information across platforms, including photos of the storm or damage, radar images, storm reports, ETAs, and the like. But the automated tweets provide an important backstop to what we do manually, they’re faster than any of us could type manually, and if that’s the only thing someone gets, they would at least know of the danger and the need to shelter or at least seek additional information.

Automatic for the People

Many broadcasters and emergency management sources felt that automation was an important tool and looked to add it to their suite of offerings. A handful of services entered this space early on, but none took hold quite like iNWS – Interactive National Weather Service. These alerts, offered only to NWS core partners like media and EMAs, are somewhat customized emails and text messages. They are fast and, most importantly for cash-strapped departments, free. They’re a great way to get severe weather information direct from the source.

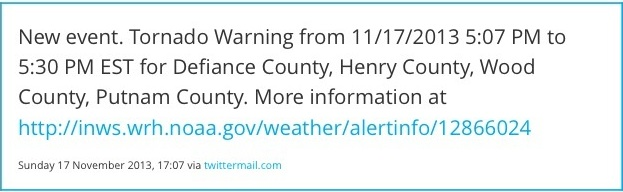

Some enterprising folks then figured out that these iNWS alerts could, through a hack involving third-party services like TwitterMail or Tumblr, be automated to social media outlets. This arrangement met a couple of primary goals: Getting the word out automatically and reliably and doing so quickly. However, when it comes to being easy to read, they leave something to be desired:

Sample automated alert.

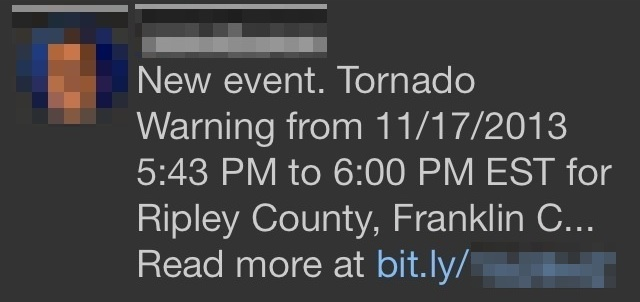

This is especially clear when these heavily formatted alerts come from different sources – or when they’re seen next to a more clearly formatted message communicating the same thing:

Comparison of alerts

One of these is not like the others – and in a very good way. Neither of the automated alerts would pass a Turing Test; they are clearly computer-generated and they are difficult to read at a glance. Beside that, they exceed the 140-character maximum for Twitter in large part because they contain extraneous information. ”New event” is superfluous, and since tornado warnings are issued on detection, they’re valid from issuance until expiration. The issue time is irrelevant, and if your system is working well, redundant, since it should be within moments of the time the tweet was published.

Contrast that with the alert from the Weather Channel’s breaking account, @TWCBreaking. There’s still some formatting there, but the key information – the “what” and “where” – are front and center. They’ve even included the expiration time. Like the automated tweets, TWC’s includes a link to more information, which is fine, but the tweet stands on its own.

A Fatal Flaw?

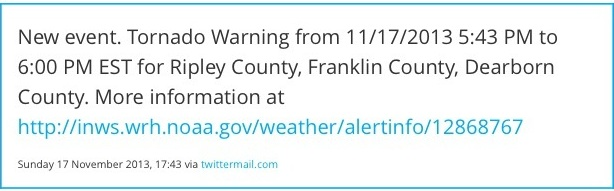

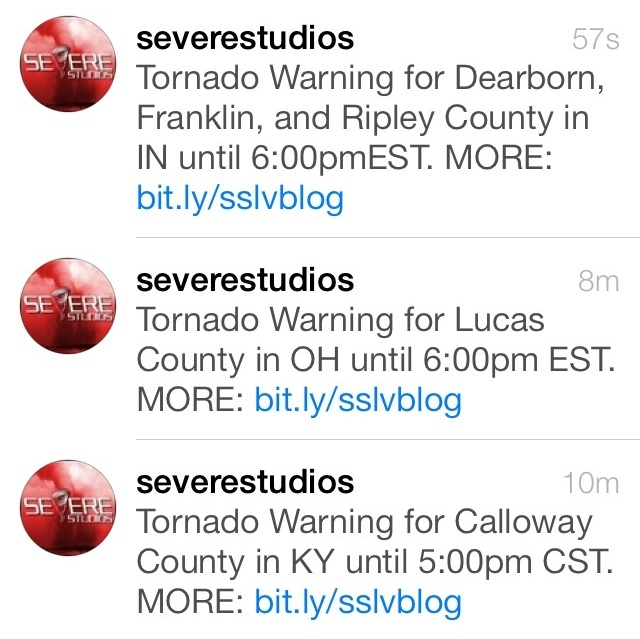

My beef with these machine-generated, user-unfriendly alerts is nothing new, but on Sunday, I noticed something far more important for the first time. At one point, I was scanning my timeline and I saw these two tweets back-to-back:

Sample severe weather tweets.

If you look closely, you’ll see the one on the bottom has three counties, while the one on the top only listed two. I took a closer look, and sure enough, they both referred to the same warning. In other words, one tweet left a county out of the warning!

Because of the extraneous information – “New event”, “from 11/17/2013 5:43PM to” and repetitions of the word “County” – the tweet was too long to fit in Twitter’s 140-character limit and was abbreviated by TwitterMail, removing vital information:

Automated tweet with a missing county

This alert was generated by iNWS and delivered to Twitter via a service called TwitterMail, which detected the overage and included a link to the full message:

What comes up when you click the link to the above tweet

Notice the tweet left off Dearborn County entirely. Were I a resident there scanning my timeline, I would have missed that my county was under a tornado warning!

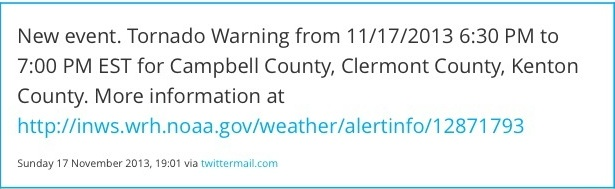

This was far from the only instance. Kenton county was left off this tweet:

Tornado warning tweet with missing county

Full information about the warning, showing all counties affected

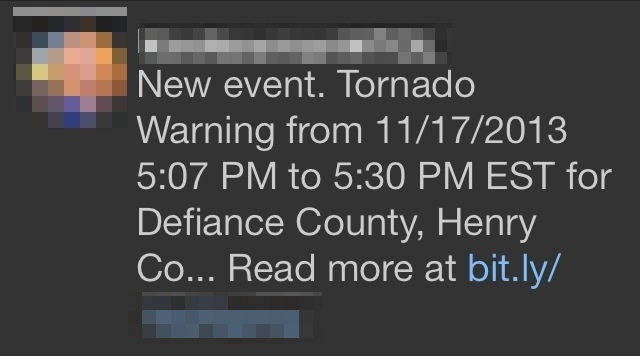

This one left two counties out of the tweet:

Tornado warning tweet with two missing counties

Full information about the warning, showing all counties affected

This wasn’t exclusive to warnings delivered by TwitterMail. Alerts via Tumblr suffered from much the same issue, leaving Trigg county out:

Tornado warning tweet with missing county

Full information about the warning, showing all counties affected

Alerting Everyone, Automatically

Again, my goal here isn’t to beat up on people trying to spread the word of dangerous weather. It is, however, to point out that we could be unintentionally making it harder for people in harm’s way to determine if they’re in a warning, and potentially, we could be leaving people with the impression they aren’t under a warning when they actually are.

This is not what any of us want, least of all the folks who figured out these connections to automate the warnings in the first place. Weather folks are often tech early adopters, and in the early days of Twitter, often it was the weather folks who were first in their station to jump on the platform. The duct-tape-and-baling-wire solution for automating tweets was fine in the early days, but it has got to go if we’re to consistently communicate severe weather threats to the public.

There are some that do it well:

Example of a complete warning tweet

Initially, I thought this was automated, but it was a copy-and-paste from NWSChat. A little more formatting than I’d like, but the extra information is useful:

Example of a complete warning tweet

Here’s another batch of good – as in “complete” and “easy to read” – tweets of tornado warnings:

Series of complete warning tweets

(To be honest, I’m still surprised there hasn’t been a solution offered by any of the TV weather graphics vendors or the various notification service/app providers for this. In the meantime, if it’s worth doing at all, it’s worth doing well, and we need to make sure we’re not unintentionally leaving folks out or giving the wrong impression.)

___

¹ They’re not perfect – I’d like to have the text be more informed by polygons, so we could tune them geographically: “northern Durham and Orange counties”, and perhaps even “including the city of Durham”, instead of just “Durham and Orange counties”. I would like to include the expiration time, as well, when space allows, but toss it when I need the characters for places. Regardless, the point here is the technology existed then and definitely exists to automate warnings in such a way that they are readable and useful.

Dan Satterfield has worked as an on air meteorologist for 32 years in Oklahoma, Florida and Alabama. Forecasting weather is Dan's job, but all of Earth Science is his passion. This journal is where Dan writes about things he has too little time for on air. Dan blogs about peer-reviewed Earth science for Junior High level audiences and up.

Dan Satterfield has worked as an on air meteorologist for 32 years in Oklahoma, Florida and Alabama. Forecasting weather is Dan's job, but all of Earth Science is his passion. This journal is where Dan writes about things he has too little time for on air. Dan blogs about peer-reviewed Earth science for Junior High level audiences and up.