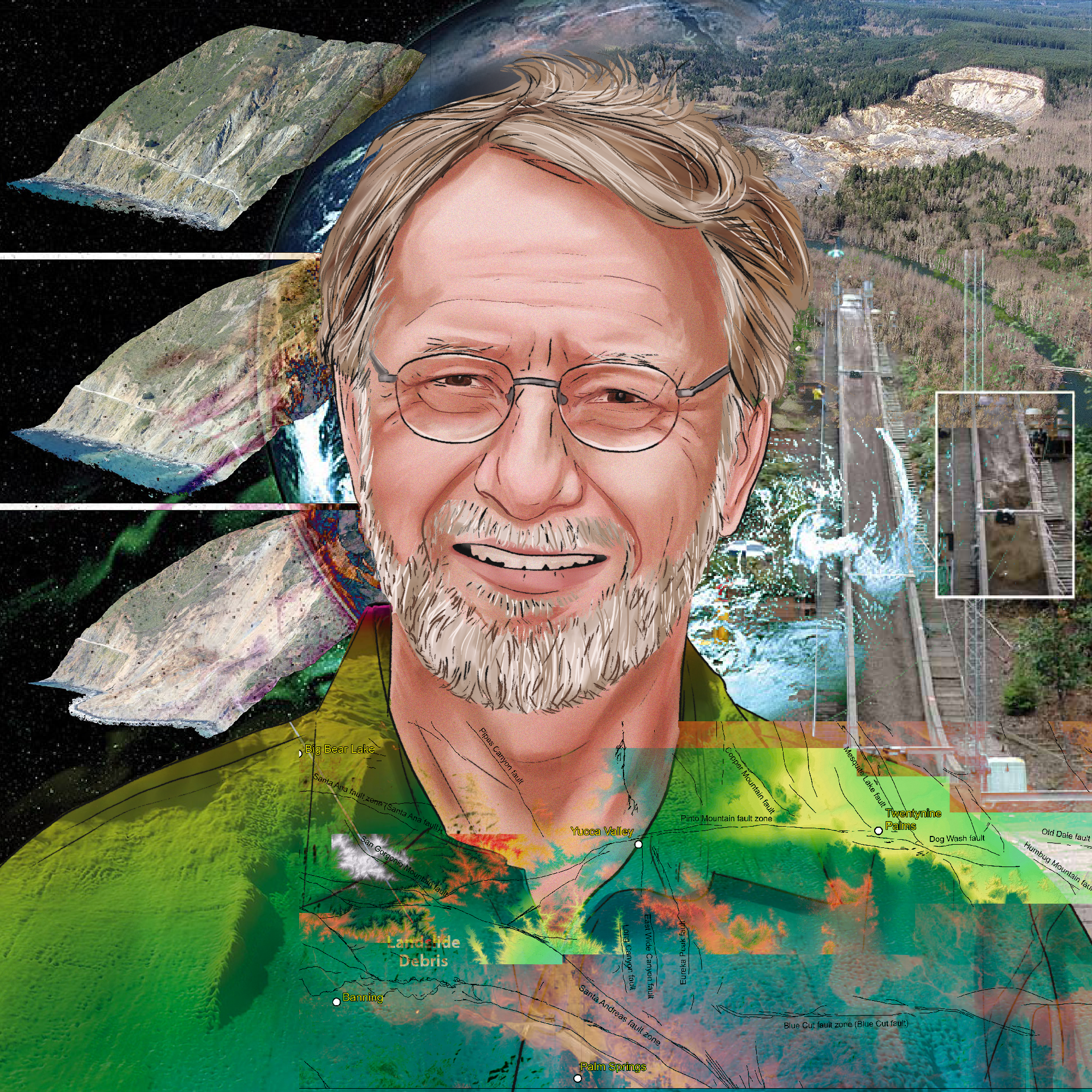

24-Storied Careers: Gaining a footing in landslide science

How do you study something that’s constantly shifting? That’s the challenge that USGS geologist Richard Iverson faced when he began his career in landslide research. He and his team developed a first-of-its-kind experimental facility to study how landslides happen, in order to better understand and prepare for them.

How do you study something that’s constantly shifting? That’s the challenge that USGS geologist Richard Iverson faced when he began his career in landslide research. He and his team developed a first-of-its-kind experimental facility to study how landslides happen, in order to better understand and prepare for them.

This episode was produced by Molly Magid and mixed by Collin Warren. Illustration by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:00 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 All right. I have to know. I don’t know why I have to know, but I want to know.

Vicky Thompson: 00:08 I was up all last night thinking about this.

Shane Hanlon: 00:10 Yeah, exactly, and not just three minutes before we hopped on this call today. Are you a fan of Fleetwood Mac?

Vicky Thompson: 00:20 Fleetwood Mac? I really like Fleetwood Mac, but I feel like I never… I haven’t gotten fully into it. I have a real surface level love of Fleetwood Mac, popular songs.

Shane Hanlon: 00:30 That was a heck of a pregnant pause.

Vicky Thompson: 00:31 Yeah, well I was trying to figure out how to say… because I like them a lot. I like them when I hear them.

Shane Hanlon: 00:38 Gotcha. See, I feel like that’s a good way of putting it.

Vicky Thompson: 00:41 Yeah. And I have their albums, right?

Shane Hanlon: 00:44 Sure.

Vicky Thompson: 00:46 But yeah. They’re not my go-to.

Shane Hanlon: 00:49 Fair enough. Do you have a favorite song or songs that come to mind when you think of Fleetwood?

Vicky Thompson: 00:57 There’s a lot, but I like “Go Your Own way.” I like-

Shane Hanlon: 01:01 Of course.

Vicky Thompson: 01:02 … “Gypsy,” “Landslide,” with like one quiet tear coming down your cheek.

Shane Hanlon: 01:09 Aw, that is very sweet.

Vicky Thompson: 01:09 What about you? Do you like Fleetwood?

Shane Hanlon: 01:13 Yeah. I feel like my understanding or my familiarity with them is similar to yours that I don’t know if I’ve heard a Fleetwood Mac song that I didn’t like. In addition to the ones you mentioned, I like “The Chain” a lot, has a really good… When the chorus hits-

Vicky Thompson: 01:27 Oh, “The Chain.”

Shane Hanlon: 01:27 … it’s really driving. For legal reasons, people aren’t hearing any of these things. You’re going to have to do some Googling on their own. But yeah, I don’t know. Who doesn’t like Fleetwood Mac?

Vicky Thompson: 01:37 Who doesn’t like Fleetwood Mac? I don’t know. You say you don’t like the songs, but you had a really strong reaction to “Tusk.”

Shane Hanlon: 01:45 Oh, I didn’t love “Tusk.” That’s all I have to say about that.

Vicky Thompson: 01:53 I got to watch you hear it for the first time in real time. It was like those YouTube videos.

Shane Hanlon: 02:01 There’s a reason why this is an audio only medium.

02:09 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:19 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:20 And this is Third Pod From The Sun. Okay. So there is, as always, a reason why we muddled through a discussion about Fleetwood Mac. And so to help explain it, I’m going to bring in the producer for this episode, Molly Magid. Hi Molly.

Molly Magid: 02:42 Hi Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 02:43 Okay, so why Fleetwood Mac?

Molly Magid: 02:47 It’s a good question. Their song…

Vicky Thompson: 02:51 That is the question.

Shane Hanlon: 02:53 Oh, I love the sigh, like, “All right, here we go.”

Molly Magid: 02:57 I know. It’s like everything that has gone on in my head, I’ve trying to explain. Okay. So their song “Landslide” has been stuck in my head the whole time I’ve been working on this episode because we’ll be talking about landslides. And I was also really partial to “I Feel The Earth Move Under My Feet” by Carol King.

Vicky Thompson: 03:18 Oh, that’s a good one. But you can’t just say it. You have to sing it. I’m not going to sing it.

Shane Hanlon: 03:23 Come on, Vicky, sing it.

Vicky Thompson: 03:25 I feel the earth move. Like that, you have to really…

Shane Hanlon: 03:28 Oh man, that was… I can’t. All right, so we’re just going to keep powering through this. So beyond this kind of musical exploration of songs related to natural disasters, what, you said landslides, but what are we actually getting into today?

Molly Magid: 03:45 Well, we talked with Dr. Richard Iverson, who’s a geologist studying landslides, how they move and how to predict them.

Vicky Thompson: 03:53 And to remind everybody, this is part of our current mini-series where we talk to scientists who have written for AGU’s Science Storytelling Journal, Perspectives of Earth and Space Scientists.

Shane Hanlon: 04:05 Great. Let’s hear from Richard.

Richard Iverson: 04:14 My name is Richard Iverson. I am a research scientist emeritus at the US Geological Survey’s Cascades Volcano Observatory.

Molly Magid: 04:24 And what is your research about?

Richard Iverson: 04:27 In a single word, landslides, but that’s a little bit simplistic. Really what the great majority of my work is focused on is a type of high speed landslide called debris flows and then sort of their close relative debris avalanches. And the only real important difference between those two is that debris flows are generally saturated with water, and partly as a consequence of that, they’re more mobile than debris avalanches, but both of them can move really fast, meaning hundreds of miles an hour in some circumstances, which of course makes them very significant hazards.

Molly Magid: 05:04 Can we back up just a little bit? I’m not sure I know what a landslide is. Could you explain it?

Richard Iverson: 05:11 Well, landslide is really any mass of earth material that moves down slope under the action of gravity. And so landslides range from those that move imperceptibly slowly, I’ve studied one slow moving landslide that moves less than a meter a year on average, and that can continue for centuries or even millennia, and then at the other extreme are these high speed kinds of landslides that happen abruptly, usually on big mountains and in the case of the landslides I study largely on volcanoes, but they can literally move hundreds of miles an hour. They happen at all scales and all speeds. Yeah, so there’s a great diversity of things that we all lump together and call them landslides.

Vicky Thompson: 06:05 Okay. So that’s interesting that there’s such a range in landslide speed. I’ve only thought about the ones that happen really quickly and suddenly.

Shane Hanlon: 06:14 Right. Richard mentioned ones that can last for centuries or millennia. I mean, that’s incredibly slow.

Molly Magid: 06:21 Right. He said you wouldn’t even be able to see that sort of landslide moving. You have to use special instruments to measure them and detect them.

Shane Hanlon: 06:31 Okay. So speaking of detecting and measuring landslides, how does he do that?

Molly Magid: 06:37 Well, a lot of Richard’s work has been around just how to do that, actually you study landslides because they can happen very abruptly.

Richard Iverson: 06:46 You generally don’t know when they’re going to occur and just as important, you really don’t know how big they’re going to be in advance. And so if you take the research approach of, “Well, we’ll set up equipment here in this locality thinking we’ll catch the next one,” maybe the next one is 10 times bigger than you anticipated and it simply sweeps all your equipment away. That’s actually happened to me in one instance. Fortunately we weren’t there at the time, but it took all our equipment away. And so really it’s for that reason that a big part of my research career ended up being devoted to conducting experiments, lab style experiments, but at a very large outdoor scale.

07:25 And the beauty of doing controlled experiments is that we can control so many things about the landslide we’re studying. We control its size, we control when it’s going to happen, at least to a large degree, and we control its composition, what kinds of sediments is it made of, how much water does it have in it, and so forth. And so that really… doing those kinds of experiments was sort of a major crux of my career, even though what attracted me to the field in the first place was the field experiences. That’s always the exciting part for most geophysical scientists is actually seeing the real thing out in the field.

Molly Magid: 08:05 So you’re making a landslide in the field. How… I just can’t wrap my head around that. What does that look like? What do you have to bring in to actually make them?

Richard Iverson: 08:18 Sure. So the way we did it was we built a unique large scale experimental facility. And so other people have triggered landslides in the field by taking a natural slope and adding water, that’s the usual strategy to try to get it to go. We tried that as well and it just didn’t work out very well for us, and so we ended up building this big facility, which at the time was unique. Any place in the world, there was nothing like it. And it enabled us to sort manufacture a set of what in the mathematical world we call initial and boundary conditions, meaning we have all kinds of ways of constraining exactly what’s going on at the onset of motion, the kind of surface the landslide will be moving across, its composition and so forth, and that really allows us to sort zero in on some important aspects of the process that would be very difficult to parse out just based on field observations or data.

Molly Magid: 09:19 So you’re putting material into this machine or into this design thing, you put in rocks and soil and water?

Richard Iverson: 09:30 Yeah, so sure, we call this facility the debris-flow flume, the USGS Debris Flow Flume, and what it basically is just a big concrete shoot on a steep hillside. And by big I mean it’s about 100 meters long, it’s two meters wide, 1.2 meters deep, and it’s steep, it’s on a 31 degree slope. And 31 degrees is about the angle that, for example, a pile of sand would stand at if you make the pile of sand as steep as possible and then just let the sand sort of slide down on its own. That’s about 31 degrees. It’s pretty steep. It’s steeper than most rooftops, it’s steeper than most ski slopes. So it’s not a trivial amount of slope to work on.

Molly Magid: 10:16 That sounds like the most extreme and fun playground slide.

Richard Iverson: 10:20 Yeah, no, I mean these experiments, doing these experiments, which I was involved with for well, really close to 30 years, it really is a lot of fun. There’s an awful lot of hard work involved as well because we’re working with large masses of natural or close to natural earth materials, basically meaning sand and rocks and mud and so forth and you’ve got to get that stuff to the top of the slope. Typically we’d use about 10 cubic meters and some experiments we’d use more than that, but 10 cubic meters is many, many tons of material.

10:55 And so we would haul it to the top of the slope using a dump truck and then load it using a front end loader, just sort of standard construction equipment. But then there was a whole lot of just brute force shovel work that needed to be done as well to kind of get it positioned just the way we wanted to install all of our instruments and so forth. So I would often characterize these experiments as 10 or 20 seconds of high drama and excitement packed into two or three days of work. So that the exciting part was over pretty quickly, but it could be really, really exciting when we let these things go.

Molly Magid: 11:34 Yeah, I can imagine watching them is just amazing. Do you have any fun or funny stories, either from those experiments or from the field?

Richard Iverson: 11:50 Oh yeah. I mean there were lots of funny incidents over the years at the flume, some of which were sort of contrived, some of which were down right scary and funny only in retrospect. I mean, one example of that was fairly early on, just a few years into our experimental work there and we would have a rotating crew. We had a core group of people who were there for pretty much every experiment, but then we’d have helpers who were there just now and then, and so one of these infrequent helpers we’d positioned out at the foot of the flume in what we called the runout area to simply videotape this big high speed flow coming down. And because he didn’t have experience working at the flume, I think he didn’t have a real appreciation of just how fast this thing would be coming and because he was watching it through the viewfinder of a video camera trying to track the moving front, he didn’t really appreciate how rapidly it was approaching him. And so basically the thing overran him, it knocked him down.

12:57 His humorous characterization of the after effect was that every orifice of his body was filled with mud. It knocked him down and what was most serious is that it broke his glasses and a piece of glass got into his eye. And so I had to rush him to the nearest hospital, which was about an hour’s drive away down in Springfield, Oregon, and fortunately at the hospital they were able to get the glass out and so on. But it was still a pretty traumatizing experience and one that we learned from. And we had some other near misses. But I’m also just thinking of some sort of stunts that were, or practical jokes, that were played on me. I remember once we had a film crew there, and over the years we had quite a few film crews at the Flume because it was an exciting thing to watch, and this particular crew was making a children’s program, I don’t remember the name of it, but it was some sort of a science program really aimed at young kids and they had this childhood star of the program.

14:03 I think her name may have been Vanessa, but I’m not certain about that. Anyway, I was working at the top of the flume where I always was when we were around on these experiments, because I would always do the final check to make sure everything was ready at the top before we let this thing rush down the slope. And so it was sort of all systems go and I gave the go ahead and the switch was flipped and down rushes the debris flow, and now I look down at the foot of the flume and here’s this person standing right at the mouth of the flume and just not moving, just standing there stalk still waiting for this thing to come down. And I screamed at the top of my lungs, they probably heard it in the next county. And then I was just horrified to see this person just being not only overrun by the debris flow, but just knocked a long distance into the air and so forth.

14:57 Well turned out that what they had done is they had put a dummy at the foot of the flume just to make exciting video, I guess, and did not disclose that to me. So that was a moment of terror on my part when I saw that happen.

Shane Hanlon: 15:19 Oh my gosh, I can’t get this picture out of my head. Imagining him screaming, “No, Vanessa,” just like at the dummy.

Vicky Thompson: 15:28 Yeah. I wonder if I could find a clip of that episode. I want to know more about it.

Shane Hanlon: 15:33 We’ll do some YouTubing and see what we can find.

Vicky Thompson: 15:33 Yeah.

Molly Magid: 15:36 Yeah, same. That would be so funny. But in all seriousness, if it was a real person, that would make for a pretty traumatizing episode of kids’ TV.

Vicky Thompson: 15:44 Oh, that’s true. I guess rocks hurdling towards you at hundreds of miles an hour, that’s not funny.

Molly Magid: 15:52 Yeah, definitely. But Richard often says, people do underestimate how dangerous landslides can be.

Richard Iverson: 16:00 Particularly if people have been living at the foot of a mountain somewhere and they’ve maybe been part of a family that’s been living there for generations and nothing bad has happened and so they think of the mountain as being just a stable part of the environment that’s really never going to change much. But then something happens and it might be a dramatic trigger like a big earthquake, but it could also be really no perceptible trigger, that things just get weaker with time and then eventually give way. So yes, people often do underestimate the threat. And one really dramatic example of that in my experience was the Oso landslide in Northern Washington state back in 2014, which was a case where there was really, by the standards of Washington state, not a very steep slope, not a very tall slope, only about 180 meters high.

16:55 And it had been chronically unstable for many years and people who lived at the foot of that slope were aware of that chronic instability. But it had always just been kind of a, I guess what I’d call a nuisance in the sense that it caused a little bit of minor flooding, some debris would come down and partly cross the adjacent river and cause some water to back up. But never a need for people really to evacuate or anything like that. It was just a nuisance. And then when the Oso landslide happened in March of 2014, it was not only much larger, but also much, much faster than anything that had ever happened there before. And the results were devastating. It was the deadliest landslide in the history of the United States, with the exception of one event that occurred in Puerto Rico back, I believe in the 1970s.

Molly Magid: 17:44 How do you communicate with people to try to get them to understand that significance?

Richard Iverson: 17:52 In terms of communicating, that’s really been a big part of my career. And something we finished just recently, just finished this last spring, was a big report on forecasting the behavior of lahars, which are very large volcanic debris flows, basically, coming down from the west side of Mount Rainier, and the west side of Mount Rainier is known to be an unstable, or potentially unstable, sector of Mount Rainier. And so in that case, we developed a very detailed numerical model of this process and created not only lots of still graphics, but also animations or movies, movies of the animated view of these simulation results. And those movies really for a lot of people… things that are difficult for them to grasp, just looking at a map, for example, and certainly looking at something like a table of data, seeing those animations where it really looks like the real thing really I think is an effective tool for communicating the nature of the hazards.

18:56 And in some respects it can scare people, but it can also edify people in other respects just because it gives them a much more realistic impression of what could happen. I mean, it reminds me a little bit of when I was a young kid, I was interested in dinosaurs and I remember hearing adults tell me, “You just can’t possibly imagine how big these dinosaurs were.” And so in my mind, I developed this picture of the single footprint of a dinosaur covering the entire state of Iowa where I grew up or something. I mean, that’s what I imagined when they said, “You just can’t possibly imagine.” And of course, I think the same thing can happen with regard to some of these destructive geophysical events that they can be big and bad, but putting constraints on that and providing people with real information and movies where they can see something play out in real time is really effective at communicating the nature of the hazard.

Shane Hanlon: 20:05 Yes. Yeah, this is what communication’s all about, this is why we do this, Vicky’s such important work.

Vicky Thompson: 20:15 Such important work, great reverence. But I think anyone who’s listening to the podcast is probably pretty interested in science communication, so they know what you’re talking about as well.

Shane Hanlon: 20:25 Right. Okay. So we know that communication is really important, but what else can be done to mitigate or prevent landslides?

Richard Iverson: 20:34 Well, for the most part, we can’t really prevent landslides except in rare instances where there’s some very high value structure that we know is in potential jeopardy. And so to give you an example… I really can’t think of a particularly good example in this country, but in Japan, which is a country with a much higher population density, of course, and also is almost entirely mountainous, there are locations where they’ve gone to extraordinary measures to try to stabilize slopes. And one approach is to simply drain them, to do a bunch of drilling and install various kinds of drains and maybe even pump water out. You can also build structural supports to help hold it in place. Now that happens in this country too, but generally on a much smaller scale with small landslides along highways and that sort of thing.

21:25 But for the really big landslide, there’s really nothing we can do to prevent them. And so it really becomes more a matter of trying to forecast what might happen and what the probability of that event might be. And the probability is a really tough one because unlike earthquakes, for example, which recur on the same faults over and over again. I mean, a classic example being the San Andreas fault, landslides, the really big ones anyway, don’t recur over and over again on a time scale that really means very much to humans. Maybe the same volcano flank fails once every a hundred thousand years, but a hundred thousand years is a number that humans have a hard time dealing with.

Molly Magid: 22:13 Yeah, that’s interesting. So it’s more about just trying to predict and make sure that people are aware of the landslide risk and hopefully there aren’t big structures or things in the way that could cause a big disaster.

Richard Iverson: 22:30 Yeah, and I mean, you just mentioned big structures in the way, obviously a better understanding of the hazard can provide guidance for where you want to situate crucial infrastructure or expensive structures or whatever to try to minimize how much they’re jeopardized.

Molly Magid: 22:50 That makes a lot of sense. So I know you’ve had a career that has spanned decades and you’re continuing your career, obviously, but I’m curious, what are you most proud of?

Richard Iverson: 23:02 I think when I’m most proud of in my career is two things that kind of go hand in hand. One was the fact that we created and successfully operated the debris flow of flume, which to this day is a unique facility anywhere in the world. And that really went remarkably well. And the thing is, there was a lot of risk involved at the front end of that because there was certainly no guarantee that we were going to be able to make this work and successfully create debris flows and landslides that helped us learn things about natural events. But that did work out and I’m really pleased that it did. And also the fact that it enabled lots of other people to be involved with that work and that has now kind of propagated and is carrying down to a new generation of researchers and so forth.

23:56 And then hand in hand with that, along with all of the experiments the whole time I was working on development of mathematical models to simulate these events, and as it’s turned out, that has paid nice dividends as well because the model, beginning about eight years ago, really reached a point of fruition where it really became a useful practical tool. And so now we really are using that model to make real world hazard assessments and to create these animations that we can show to people to help them understand the nature of the hazard and so forth. And so I feel really good about the fact that the work has had a real practical application.

Molly Magid: 24:40 What is the most fun or exciting part of your work?

Richard Iverson: 24:45 Well, I would say the most fun part… so right now I’m involved in a little consulting project just here on my local mountain, Mount Hood, which I can see outside my window here, and what’s fun about that is just going out… so the issue there concerns potential hazards to a dam that’s going to be rebuilt downstream from the north side of Mount Hood. And so the question is, what is the likelihood that some sort of big flow event, a landslide or a lahar or something, could impact that dam?

25:20 And what’s fun about that is I basically get to go out and hike around and draw on all my prior experience to put this into some rather compact and coherent package to explain to people what the issues are or are not in that location. And that’s just fun and it’s gratifying. I mean, that’s not the most exciting part. The most exciting part was when we were making original discoveries at the debris flow flume and literally learning things that nobody had ever learned before. And anytime you feel that you’ve been managed to do that, that you’ve had an insight that no one to your knowledge has had before, that’s just a real source of excitement.

Molly Magid: 26:10 Yeah, absolutely. Could you tell me in one or two sentences why your research is so important?

Richard Iverson: 26:19 I think the research that we’ve done and others have done on landslide and debris flow dynamics is important because of the role that it can play in informing people of what hazards are and then taking necessary steps to reduce people and properties’ vulnerability to those hazards.

Molly Magid: 26:40 Yeah. At the end of the day, it’s about the people.

Richard Iverson: 26:43 Right.

Vicky Thompson: 26:50 That’s a really nice sentiment.

Shane Hanlon: 26:51 Yeah. Yeah. It’s just like this podcast, we’re all about the people as well.

Vicky Thompson: 26:58 You’re really on your soapbox today.

Shane Hanlon: 27:02 I don’t know what to say and I don’t know something just about Fleetwood Mac just puts me in the mood.

Vicky Thompson: 27:07 Ooh.

Molly Magid: 27:08 Oh man, I did not realize I was going to bring this energy into the episode. I guess all I can really say now is I think I’m going to have to go my own way.

Shane Hanlon: 27:16 (Singing).

27:21 Yeah, see? Vicky, you did it before so I have to go on and do this one.

Vicky Thompson: 27:24 You have such a beautiful singing voice.

Shane Hanlon: 27:26 Oh yeah, my awful falsetto. Yeah. We’ll just… We will leave things there for now. And so that is all from Third Pod From The Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 27:35 Thanks so much to Molly for bringing us this story and to Richard for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 27:40 This episode was produced by Molly with audio engineering from Colin Warren, artwork by Jace Steiner.

Vicky Thompson: 27:46 And we’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast. Please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 27:55 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 28:01 Can you hear them upstairs now?

Shane Hanlon: 28:03 No.

Vicky Thompson: 28:04 Okay, because everyone is home upstairs.

Shane Hanlon: 28:10 Oh, what are they doing? Are they having a dance party? Are they listening to Fleetwood Mac?

Vicky Thompson: 28:12 Probably.

Shane Hanlon: 28:13 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 28:14 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 28:15 What would be the Fleetwood Mac song that they would dance to?

Vicky Thompson: 28:20 Well definitely “Go your own way” but-

Shane Hanlon: 28:23 Definitely go your own way, right?

Vicky Thompson: 28:28 “Gypsy” is a good one, especially-

Shane Hanlon: 28:28 Which one?

Vicky Thompson: 28:28 “Gypsy.”

Shane Hanlon: 28:28 Oh yeah, “Gypsy” would be good.

Vicky Thompson: 28:40 Yeah, because it’s like, for Olivia, anything that she could get a good spin going. For my daughter, that’s a good one.

Shane Hanlon: 28:41 I feel like, we were looking at the videos beforehand, I feel like the “Gypsy” video is kind of whimsical as well.

Vicky Thompson: 28:48 Yeah. Well, everything that Stevie Nicks wears is scarves and lots of things that flow.

Shane Hanlon: 28:55 Fair. Is that your daughter’s aesthetic?

Vicky Thompson: 28:57 Yeah. I mean, when dancing, for sure.

Shane Hanlon: 29:00 When dancing like she has specific outfits she puts on for dancing?

Vicky Thompson: 29:04 Well, yeah, she’ll be like, “Pause this,” and she’ll run in the other room and get on a dancing outfit.

Shane Hanlon: 29:09 That is amazing.

Vicky Thompson: 29:10 And then be like, “Okay, ready. Start it again.”

Shane Hanlon: 29:13 Oh, I love that.

Vicky Thompson: 29:14 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 29:14 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 29:15 She’s a little Stevie.