22 July 2019

Add common names to your manuscript and talk titles

Posted by Shane Hanlon

By Shane M Hanlon

I’m walking down a row of posters at a meeting of ecologists and see the title, Non-target effects of an organochlorine pesticide on Mentior tacomii in aquatic settings. I think, “Neat!” I studied the effects of pesticides on amphibians and reptiles as a researcher so I’m always up for learning about contamination in other systems. The problem is that I have no freaking clue what M. tacomii is. And I’m not alone.

My Ph.D. program was born out of a joint ecology-molecular biology department. Everyone was one big happy family. We had events together, sat in invited speaker seminars together, and presented our research to one another. I sat through 4.5 years of departmental seminars with friends and colleagues and to this day I cannot tell you what half of them studied. Part of that is on me – I certainly could’ve been more engaged with my molecular colleagues. But part of it was also that, while the research was interesting enough, it would take me 5-20 minutes into my colleagues’ talks to determine what exactly they were studying. I mean, not necessarily the question, but the species. What species?! And, in fairness, it wasn’t just the molecular folks. I benefitted from knowing what my ecology peers were studying, but as an outsider with no expertise in their fields, I would have no idea. And why? Because they wouldn’t list the common name of their study species in their title.

I realize that this isn’t as big of an issue in the non-biological sciences. And I realize that I work for an Earth and space society. But this is a problem. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve seen a manuscript or talk title and thought, “What the heck are they actually studying?!”

I’m honestly not sure how the practice of not including common names in scientific communication became a thing. Who does that benefit? Is the thought that it makes the science sound more official? Does is make the scientist sound smarter? Are we, as scientists outside of the field, just suppose to go along with it, acting like we know exactly what species is being talked about so that we don’t look stupid? Or, is there a legit reason?

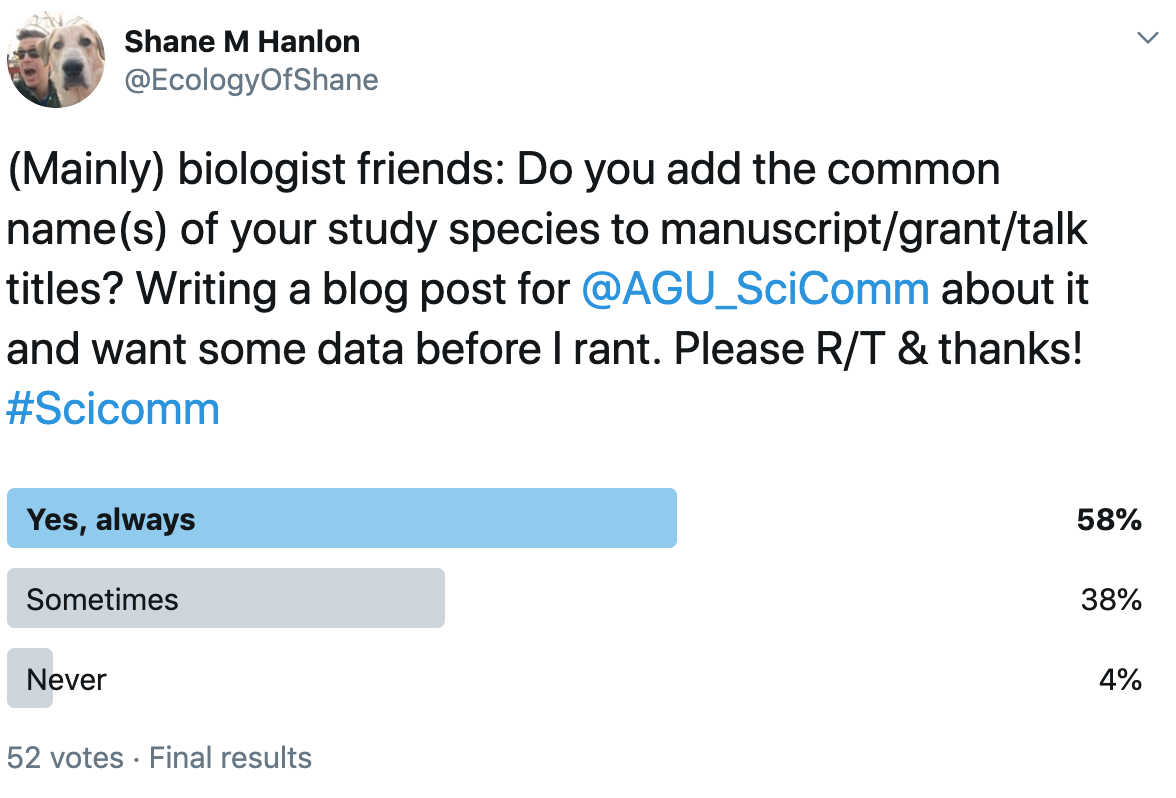

I conducted a (very) scientific Twitter poll on Friday as I was writing this post:

I honestly don’t know what I was expecting but I think I made a mistake by including the “Sometimes” option. The option is a bit too wishy-washy and doesn’t really allow me to get to the heart of what I really wanted to know but there is some good info in here. I can’t imagine a situation where I wouldn’t include a common name. What’s the value there? How does not being more descriptive enhance a manuscript? I should’ve asked my former self.

Full disclosure: I’ve done it. I’ve published manuscripts and given talks with no common names in the titles. I didn’t even know that I did it. Seriously. As I was writing this piece I thought, “Maaaaaaaaaybe I should go back and make sure that I didn’t do this-oh, crap, I did.” I don’t specifically remember my thought process, but if I had to guess, I would say that I just didn’t think about accessibility. I knew what I was talking about. My peers knew what I was talking about. That’s really all that mattered. But that’s not all that matters.

Science should be accessible. Sure, the general non-science public probably isn’t going to read your manuscript. But folks outside of your immediate field might. They might want to come to your talk or even cite your work. By not including the common name of your study species, you’re creating an unnecessary barrier to entry. Don’t do that.

Oh, and Mentior tacomii? I made it up. Mentior is latin for “to lie” and Tacoma is my dog. He’s a good boy.

–Shane M Hanlon is Program Manager of AGU’s Sharing Science Program. Find his @EcologyOfShane and browse his manuscripts with (mostly) common names listed in the titles.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

Right on, Shane! But don’t forget that overly specific technical terms are not limited to ecology and molecular biology. Geology, geophysics, and seismology and also rife with terms that needlessly limit the audience, and I doubt there are many fields that escape that problem.

A friend who wrote for the Voice of America said she was constrained to use words from a relatively limited dictionary, or explain terms outside that dictionary. She was writing for readers whose first language was not English, but substitute molecular biology (or seismology) and perhaps there is a parallel. Perhaps machine learning tools would help construct appropriate dictionaries for technical presentations?