9 July 2019

Human Rabies Mortality in India: Why Is This Still An Issue?

Posted by Shane Hanlon

This is part of a series of posts from our own Shane Hanlon’s disease ecology class that he’s currently teaching at the University of Pittsburgh Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology. Students were asked to write popular science posts about (mostly) wildlife diseases. Check out all the posts here.

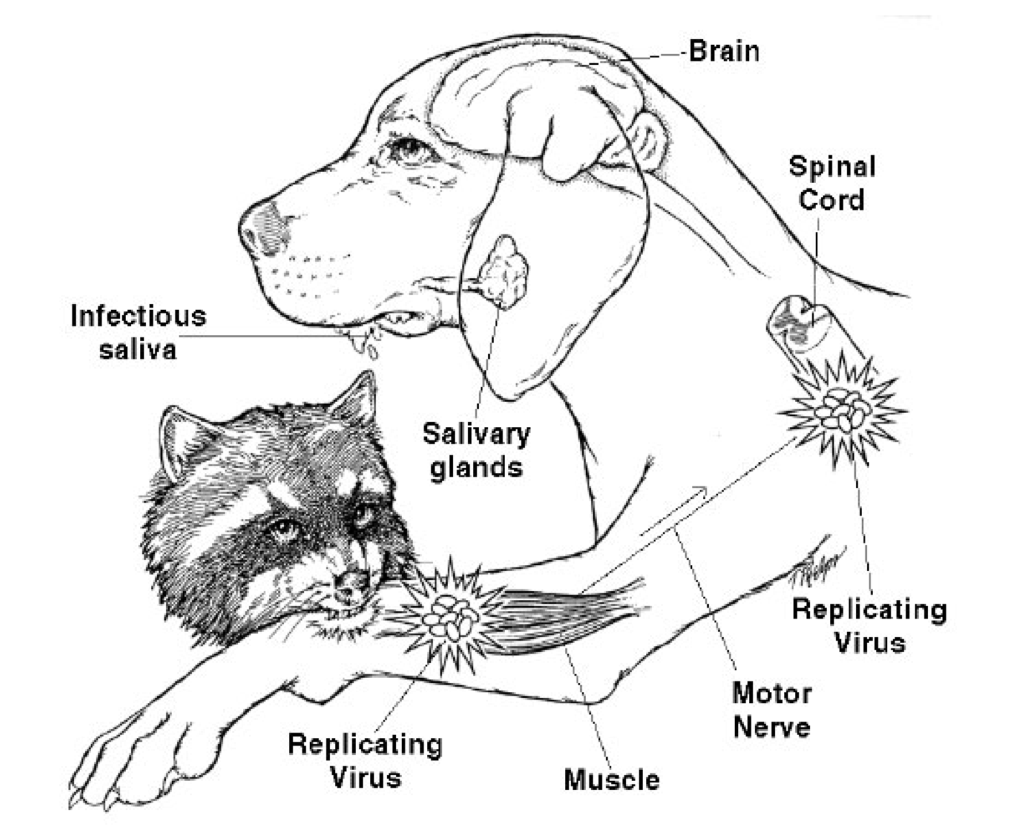

Effects of rabies bite. Credit: CDC

By Katie Jones

There are an estimated 25 million stray dogs within the country of India. These animals serve as carriers for one of the deadliest diseases in the world – one that has ravaged the country and surrounding areas within Southern Asia. This disease is rabies, and India makes up 36% of the world’s rabies deaths each year. About 30% to 60% of rabies victims within countries where the disease is endemic are children under the age of 15. Some of them don’t even know they’re infected until symptoms begin to show and it’s too late.

Many children are brought to hospitals in need of treatment after symptoms have started to show, seeking help from medical professionals who unfortunately can’t help. After symptoms appear, rabies is 100% fatal. The affected individual – after suffering a bite, scratch, or contact with an infected stray dog in this case – should seek immediate treatment after the interaction. When caught early enough, rabies doesn’t have to result in death. However, the most affected populations within India are those suffering from poverty or the uneducated. This fact matters.

Poverty, education, and power are not mutually exclusive. These three feed off each other, creating a vicious cycle that may be near impossible to escape. Now throw a fatal disease into the mix, and we have a dangerous human rights crisis on our hands. How do we protect the most vulnerable in the population?

There are some strategies being utilized presently to control the disease’s spread. One measure being taken is the vaccination of dogs and maintaining the immune coverage. However, a major problem with this strategy is the control of the dog population. With how many stray dogs there are in the country and the movement of dogs from adjacent affected areas, India is severely lacking in funding and human resources. The Indian government is also focusing on raising awareness through programs. In 2008 in five different cities, the National Centre for Disease Control started a pilot project in the hopes of preventing human rabies deaths. It includes training medical professionals on animal bite management, and raising awareness through social campaigns about post-exposure treatment. Treatment has also become less painful and cheaper after the switch from nerve-tissue based vaccinations to cell-based vaccines.

This is great progress and helpful initiatives, but something doesn’t add up here. We have a disease that is completely preventable and treatable if caught in time, yet India reports approximately 20,000 deaths a year from human rabies. What are we missing?

We’re so focused on the disease that we’re missing the big picture. The biggest problem isn’t with the disease itself, but with the circumstances that make people vulnerable. Most disease in lower-income countries is not caused by a lack of innovation or treatment, but poverty. The real problem then becomes access – to education and treatment. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 65% of the population in India lacks access to essential medicines. India also tacks on some of the highest taxes and tariffs to retail medicine in the world, with the combined impact of duties and taxes on retail medicine prices estimated at 55%, compared to the global average of 18%. On top of that, government spending priorities that siphon money away from healthcare infrastructure is also an issue. People living in poverty are less likely to be educated or have money for treatment, and more likely to live in less-than-ideal conditions like poor sanitation or restricted access to healthcare. If we want mortality caused by preventable and treatable diseases (like human rabies) in lower-income countries to drop, we need to focus on the real issue: poverty.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.