28 March 2017

How stories captivate an audience

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

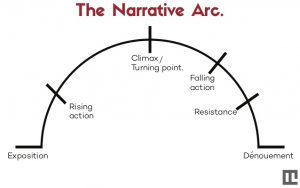

A typical narrative arc. The horizontal axis represents time; the vertical axis represents the amount of tension. So as the story progresses, the tension should build and then release.

By Lauren Lipuma

In AGU’s Sharing Science communication workshops, we always stress the importance of storytelling. Stories are what draw people in and allow scientists to connect with their audience.

But what do we mean when we say, “tell a story”? First, we mean have a narrative arc – a chronological depiction of a series of events.

Second, it should be about people – what they experience, what they feel, how they grow and change.

Here, I’d like to show what a difference a story makes when communicating science, using two documentary films as examples. I’ll identify the relevant story parts of one film and describe how the story contributes to the film’s success. Then I’ll discuss one film where storytelling is virtually absent.

Chasing Ice

Chasing Ice is a 2012 film about James Balog’s project to photograph the effects of climate change on glaciers in the Arctic. The first ten minutes of the film are dedicated to the opening exposition, where James describes the project he is about to begin and how it came about. Part of that exposition is shown in the following clip.

This exposition alone gives you the gist of the film. James wants to change people’s minds about climate change by photographing ice. You also get a sense of the narrative theme: it’s a quest, a journey, to make people accept the science of climate change where before they didn’t.

After the opening exposition, you have the rising action. James creates the Extreme Ice Survey and begins his project. His initial goal is to place 25 cameras on Arctic glaciers for three years and have them photograph the changing landscape.

You watch as James and his team position the cameras and you see the obstacles they face as the project progresses. The cameras are damaged by wildlife and buried under snow; the timers continually fail; batteries explode. At one point, James realizes he must completely redesign the electronics controlling the cameras’ timers. In this clip, you witness his frustration at the setback and his despair of ever getting the project off the ground.

After building the tension with the obstacles, we get to the film’s climax. After replacing each camera’s voltage regulator and waiting six months, James treks back out onto the ice and finds that it’s worked: the cameras are shooting. Then you have the falling action, where James collects the photographs and compiles them into stunning time lapse videos. The final part of the film is the resolution, where James shares his photos and the world reacts.

It’s important to note that climate change is only half of the story of Chasing Ice. The other half is about James himself and his personal quest to capture these photos. In a way, the film is more effective than James’ photographs alone. By adding James into the story, it becomes much more personal. The film creates an emotional connection between the James and the viewer that is hard to dispel. You find yourself rooting for James to win and feel a sense of completion when he does.

Into the Inferno

One example where storytelling is missing from a film is Into the Inferno, a 2016 documentary exploring the relationship between humans and volcanoes.

The film follows volcanologist and co-director Clive Oppenheimer as he travels to various volcanoes around the globe. Here there is no opening exposition: we don’t know what the film is about or why the filmmakers are making it. The closest we get to an exposition is when Clive says the film started for him in Antarctica, but he doesn’t say what he wants to accomplish with it.

For each place Clive visits, he recounts the relationship humans have had with that particular volcano. Each one of these segments could be a story in itself, but none are told from beginning to end, making each part feel unfinished and disconnected from the rest. At one point, Clive goes to the Afar region in Ethiopia, following scientists looking for fossil evidence of what happened to humans after an eruption of Indonesia’s Mt. Toba 74,000 years ago. Professor Tim White almost becomes a character in the story, but then we leave the Afar region without ever finding out if Tim finds the answers he’s looking for.

While the film is visually stunning, there isn’t one main story arc to tie each piece together. Oppenheimer discusses the symbolism of volcanoes but there is no arc or theme, no buildup and relief of tension. Clive could be considered the protagonist of the film but he doesn’t grow, change or learn anything over the course of the film.

At the end of the film I’m left wondering: what is the message? What should we take away from this? That volcanoes are dangerous? That people are fascinated by volcanoes? After watching the film several times, I’m still not sure. (I can’t even tell from the trailer.)

In Chasing Ice and Particle Fever, you can clearly identify the parts of the narrative arc and see how they tie the story together from beginning to end. Both films are captivating, personal and emotional. But if you’re still unsure of just how powerful stories can be, watch this woman’s reaction to seeing Chasing Ice for the first time.

—Lauren Lipuma is a public information specialist and science writer at AGU. You can follow her on Twitter at @Tenacious_She.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

Hi, I really like this post and am hoping to use it in a science communication seminar this week, but the first two videos won’t work. Do you expect to have this fixed soon?