1 December 2010

Communicating climate science with blogs and apps: Q&A with John Cook (Skeptical Science)

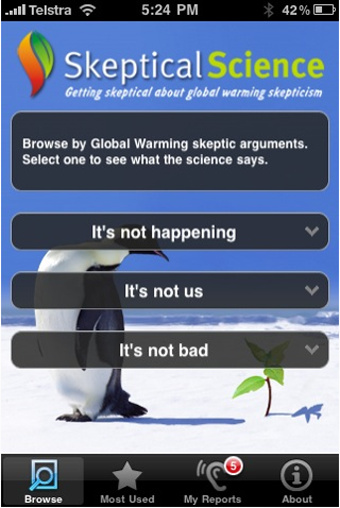

Over the past three years, climate science blogger John Cook has become well known for his website Skeptical Science, which takes on common arguments from climate change skeptics with a user-friendly database of peer-reviewed research. Earlier this year he also launched a Skeptical Science iPhone and Android app. To date, the app has been downloaded 60,000 times. The Plainspoken Scientist spoke with Cook from his home in Australia about effective climate science communication and the line between advocacy and arguing sound science.

The Plainspoken Scientist: Tell us a bit about how Skeptical Science came about?

Cook: I started having discussions with family members and a few of them were skeptics. One of them gave me a speech by a U.S. Senator, Sen. [James] Inhofe of Oklahoma, he’s the guy who said that global warming was the biggest hoax in American history. I had a read through the speech and started looking at all the scientific arguments in it, which there weren’t that many, but all the science in there was way off base compared to what my research was telling me. So I started collecting skeptic arguments and building a list and then trying to find what the peer-reviewed science said about each argument.

TPS: This year you added the Skeptical Science app as well. Can a phone app be effective at communicating science?

Cook: Definitely. When our app came out it really took the website up to another level. There’s been at least 60,000 downloads so far, so a lot of people are using it. I get anecdotal stories from people saying how when they’re having a dinner table argument with their crazy uncle they can just whip the app out and produce the science. People don’t go reading peer-reviewed journals, so this is a way of packaging the science so that the average person can use it.

TPS: You’ve been blogging on the site for several years as well. Is that something you believe can impact the broader climate debate or do you ever feel like it’s preaching to the choir?

Cook: There’s a bit of an element of preaching to the choir, most of your readers are people who agree with you. Like for instance on my site, I’ve kind of been keeping track of it and about 80 percent of the people who post comments would be convinced that humans are causing global warming and about 20 percent are skeptics. But we’ve already seen that blogs do have a big impact; sometimes good, sometimes bad.

My plan was always to keep my focus on where the debate was. I expected that over time I would gradually move away from the question of “is global warming happening?” to “what’s causing it?” and then as the science became so irrefutable that even skeptics would stop arguing those points. Then I could start moving my website into the questions of what to do about it. I thought that by now I would be well into solutions and writing less about what’s causing global warming, but we actually seem to have gone backwards in the debate. But the debate really does need to be about solutions.

TPS: Recently there’s been an increased interest from scientists wanting to help shape the public debate on climate change. What advice would you give to scientists about reaching out to the public?

Cook: A lot of climate scientists have trouble boiling things down to plain English that people can understand, because when you’re knee-deep in jargon all day it’s hard to stop using it. The funny thing is that I’ve found that often the non-scientists are actually better at explaining science. I think they just have ways of explaining it in a manner that the non-scientist can grasp, whereas scientists tend to lean on technical jargon because it’s more precise and less likely to be misinterpreted. It’s safer to use technical jargon because once you start using metaphors and simple language there’s a danger of being misinterpreted, but it also means you can speak more meaningfully to people. So it’s just that risk you have to take I think.

People aren’t just persuaded by facts and evidence, that’s not sufficient to get people motivated to change. It’s not enough just for climate scientists to present the facts: how we present it, and how we explain it, and which audience we’re talking to, all that matters. One thing I’ve learned is that just giving doom and gloom messages isn’t enough. Just telling people that sea levels are going to rise and that heat waves are going to make things bad can often turn people into denial. You also have to give people positive information: which is that there is hope.

– Eric Betz, contributing science writer.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

The Plainspoken Scientist is the science communication blog of AGU’s Sharing Science program. With this blog, we wish to showcase creative and effective science communication via multiple mediums and modes.

Not being an accredited scientist, but being like 99.999999 % of the rest of the people, and not having the view of things from the sources of the solar wind blocked by the trees that scientists look at, then to explain that there is no coincidence between the dimensional and brilliance increase of the mesosphere’s Noctilucent, night shining clouds, noted in early 2004, and the Oct 31, 2003 CME that zipped past our planet while dragging a lot of the chromosphere and coronal proton gasses with it, is a simple task.

One cannot drag magnetically charged positive energied protons past the negative energy magnetics that cap off the mesosphere without having some of the protons captured to the mesosphere. The reason for the Noctillucent cloud’s toroid shape is because the magnetics of the cap rise up from the ground surface plane before the polar circle, which leaves the donut hole open to the solar atmosphere as being the polar surrounds.