4 April 2017

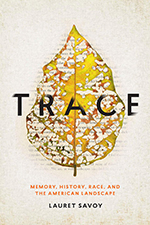

Trace, by Lauret Savoy

Posted by Callan Bentley

I just discovered a 2015 book that explores the relation between the American landscape to the history of its people, indigenous, enslaved, and enslaver. The author, Lauret Savoy, is a professor at Mount Holyoke College, where she teaches in the department of environmental studies.

I just discovered a 2015 book that explores the relation between the American landscape to the history of its people, indigenous, enslaved, and enslaver. The author, Lauret Savoy, is a professor at Mount Holyoke College, where she teaches in the department of environmental studies.

In the book, Savoy explores the combined history of place and race in several settings across the United States. She begins at the Grand Canyon, but also spends time on the shores of an island in Lake Superior, a plantation in upland South Carolina, southern Arizona’s border with Mexico, and good old Washington, D.C. California and New England make cameo appearances too. In each location, Savoy brings her perspective: the perspective of a geologist, a woman, a person who values her indigenous heritage, a person descended from enslaved Africans, a child of a writer, a child of a military nurse, a reflective soul.

This is a book in the tradition of American writers who reflect on landscape, place, and their own existence. Savoy invokes Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac early on in Trace, and I also think of A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (Annie Dillard), Desert Solitaire (Edward Abbey), and Refuge (Terry Tempest Williams). The perspectives of each of these authors is distinct, but each derives a sense of who they are from the natural landscapes that they visit. Savoy’s unique contribution is her focus on the role of race in the American story.

She does this in ways that are both searingly specific and widely applicable. For instance, Savoy is on the shore of Lake Superior, on a cobble beach. She says

Each evening on the island beach, I could touch more than a hundred stones lying within arm’s reach. Each cobble a relic of a remote past and a piece of and in this present.

Just like people. I love that. We all have histories, some dramatic and some less so. But all of us share this world here and now, and the common future contains all our myriad paths.

Slavery gets a lot of thoughtful attention in Trace, and Savoy notes that the moral abomination of slavery may be past, but its social and economic effects live on. Predecessor banks of some of America’s largest financial institutions amassed wealth via the slave economy. Hallowed educational institutions covered in ivy were made more secure and innovative as a result of bequests from wealthy enslavers. It’s sobering to realize that America is who it is because of the nation’s “original sin” of brutality and injustice.

Like John McPhee, Savoy loves words, and signals no shame in just listing them as a sort of beat meditation on place, tasting their syllables in sequence.

Place-names that might or might not have been bestowed by Indigenous peoples for those places shimmer like mirages. I live in Massachusetts. I’ve swum in the Connecticut River. I’ve spent long hours by the Potomac and Susquehanna Rivers, by Chesapeake bay. I’ve waded into the Platte, the Arkansas, the Missouri, I’ve crossed the Mississippi’s headwaters on stepping-stones. And I’ve explored mountains. Adirondack. Taconic. Ouachita. Pocono. Wasatch. Absaroka. Uinta. Appalachian.

Beautiful, right? these proper nouns are themselves objects of beauty, and deserve our contemplation. So are landform names, listed in alliterative joy on page 86:

a’a, ablation hollow, abra, alamar, alamo, alkali flats,

badland, bajada, bald, bally, banco, baraboo,

cajo, caldera, caleta, cañada, cañon, candela, cat hole, catoctin

She also plays with common verbs like “remember,” writing it as intentionally with a hyphen to break it up: “re-member.” In other words, by remembering something, we affix it to ourselves and our worldview anew. Other verbs get a similarly useful treatment, a sort of literary enunciation to extract additional meaning from words that otherwise might past unnoticed, unsavored.

The writing is, in many places, beautiful or evocative. I love how she calls the mountains of the Basin & Range province “elongate lithic compasses.” Or listen to this passage, about the passage of geologic time:

Millions of years may be lost in the gaps between black-shale laminae so thin as to be pages of a book of night. Time condensed and time eroded; punctuated discontinuity rather than layered continuity. Then mountain-building ruptured the bedrock terrain. I didn’t realize it, but we — fossils and woman — arrived to meet that day in the field., a chance moment of exposure together.

In all, I found Trace a thoughtful, thought-inducing read. I came away from it with a new sense of the different flavor that Americans with other histories, other heritages, can have to the landscape we all share. I would recommend it to you.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.