17 April 2013

Four new GigaPans from an intriguing contact

Posted by Callan Bentley

Jay Kaufman of the University of Maryland and I met in the field this weekend to do some outcrop preparation and structural documentation with the GigaPan.

This is a tricky bit of business, as it turns out – or, at least, it’s trickier than the typical GigaPan shoot.

To start with, we had to clean the exposure, a block that shows the contact between the Neoproterozoic Fauquier Formation and the overlying Catoctin Formation.To clean it, we needed a pressure washer. But there was a good sized stream between the car/road and the rock. So here’s Jay hauling the pressure washer across Goose Creek with the help of his graduate student Huan Cui.

All in the name of science.

Next, we had to haul water from a flooded quarry pond up a steep, muddy slope to the site where the intriguing rocks live. There were several slips and spills, and my cell phone took a swim in the pond. All in the name of science. Jay’s daughter Colleen was helping, too, and she hauled tools like a saw and branch loppers to the site.

We power-washed the rock, a block of float with some intriguing structure. Pond water misted surrounded us: we breathed in its microdroplets and their microbial cargo. All in the name of science.

Then it was time to GigaPan: Jay hauled a ladder over, which was key for getting the GigaPan up to a proper height for photography orthogonal to the plane of the exposure.

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

As I supervised the GigaPan (it was on auto-focus, and needs supervision in that condition; otherwise it sometimes skips a shot if it can’t decide what to focus on), Jay cast shadow on the block, so as to have a consistent level of lighting across the final image. Braving muscle fatigue as he perched on a branch for 15 minutes, between the Sun and the rock, Jay persevered – all in the name of science!

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Photo by Huan Cui, courtesy of Jay Kaufman

Here are the four GigaPans that resulted from our labors:

The happy team at the end of the expedition:

Photo by Jay Kaufman

Photo by Jay Kaufman

So what do we see in these images? I think our background strongly colors our interpretation.

Jay is a sedimentologist and geochemist, one of the four authors of the bombshell 1998 “Snowball Earth” paper that ignited the modern explosion in examining and re-interpreting Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks. He interprets this contact as showing pillow basalts, and carbonate diapirs between the pillows. This is very important, because if indeed the block records primary soft-sediment deformation (hot submarine lava flowing onto submerged carbonate mud), it allows us to use the radiometric date for the Catoctin Formation (meta-basalt / greenstone) as a constraint on the age of the underlying Fauquier Formation (meta-limestone / marble). It would mean that the relationship is conformable (and the metamorphism later overprinted the primary configuration with a light enough touch that it wasn’t fundamentally reorganized), and that helps us say when the “Ediacaran” phase of Snowball Earth glaciation took place, since the lower Fauquier shows features that are consistent with glacial outwash. Here’s my rough interpretation of this reading of the rocks:

Photo by Jay Kaufman; Click to enlarge

Photo by Jay Kaufman; Click to enlarge

Caveat: Jay and his colleagues may draw those lines differently; I refer you to their paper for a more complete discussion of their interpretation. Jay has also added snapshots to one of the GigaPans to help tell the story.

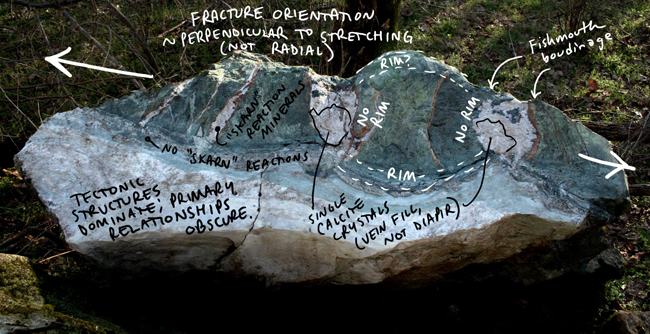

However, I’m trained as a structural geologist, and so I see something different when I look at this block. I see boudinage, tension gashes, and metamorphic reaction rims (chlorite + garnet most prominent minerals in these “skarn”-like veins), with enormous crystals of vein calcite filling most of the volume of the boudin necks. The fact is that we see the reaction rims and the multi-cm-scale calcite crystals only in the spaces between the blocks of greenstone (and not along the bottom/top contacts). The inverse is seen with the dark-colored, fine-grained “chill zone” that one might say is where the quenched obsidian formerly was located: you don’t see that in the spaces between the greenstone pods. This suggests to me that interpreting them as Alleghanian-age boudins and boudin necks is the more parsimonious interpretation. A fine way to test my interpretation would be to compare the orientation of these structures to Alleghanian-aged structures from elsewhere in the region. Unfortunately, this is a block that is displaced from its original position (float, not outcrop), so the geometry is divorced from its in situ orientation. At any rate, the pervasive Alleghanian deformation of Blue Ridge rocks gives me reason to suspect the that this contact isn’t pristine enough that I’d feel comfortable deeming it as definitely conformable.

Photo by Jay Kaufman; Click to enlarge

Photo by Jay Kaufman; Click to enlarge

Jay sees primary structures, and I see tectonic structures. Maybe there’s a bit of both?

I love this site, and the rest of the Fauquier Formation, for this reason – it’s not 100% clear what it means. That means it’s a great place to train students to think for themselves about the paths we follow from the observations we make on site (or virtually “on-site”) to the stories we tell about the past based on those observations.

Regardless of the final interpretation, these GigaPans offer plenty of information to stimulate discussion and inquiry. And the great thing about our efforts last weekend is that now everyone can “visit” these rocks and use their observations to power their own independently-formulated hypotheses.

Enjoy exploring them, and viewing them through the lens of your own training and background. Let us know what you see!

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

I look at those blocks and the 1st thing that comes to my mind is “how do you get big, isolated blocks like that out in that Maryland(?) woodlot – seemingly separate from connecting outcrops?” Regardless, they are fascinating, and I think your efforts (and results) were worthwhile.

Old quarry – These are the rejected blocks – too much greenstone; too little marble.

🙂

It really is a puzzling specimen, and you guys did a great job of cleaning it up. I’m with you in interpreting the coarsely crystalline calcite between the “boudins/pillows” as a late-stage diagenetic deposit. The calcite texture is just too different for it to have simply oozed up from a contemporaneous lime sand deposit below. I wonder what isotope or trace element studies of the two calcite areas would show? Also, those ragged shards of greenstone floating in the coarse calcite look clearly to have been wedged off the “boudins” by progressive lateral crystal growth in a vein-type situation. I can’t see that happening through contemporaneous soft-sediment squishing up from below.

On the other hand, that light green ?marble bed underlying the greenstone seems problematic to the boudin theory (I’m not a structural geologist, so I could be out of line). It appears that the light green bed is thickest adjacent to the “boudin necks”. Would that be consistent with stretching? I can’t quite make out what that pale green bed is, or even if it really is a “bed”, or perhaps just a diagenetic alteration (chloritization) that’s permeated deeper into the subjacent marble at the “neck” points.

It’s a real conversation piece, anyway! Thanks for posting it.

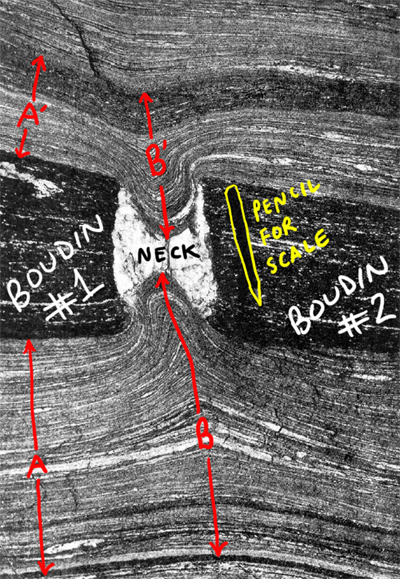

That doesn’t bug me in the least. Flow of the surrounding “matrix” into the boudin necks is a typical feature of boudinage, which only occurs where there is a marked competence contrast between the boudinaged rock unit and the surrounding “matrix” rock unit. Here’s a nice example from a book on the field geology of high-grade gneiss terranes:

Compare the thickness of the layering in the enveloping “matrix” at locations A and B (or A’ and B’). Certainly it thickens at the boudin neck.

I don’t claim to know the nature of that greenish marble layer, but I think that it’s reasonable to interpret it merely as marble that has reacted with the neighboring greenstone, though not the the same extent as the juicier setting to be found in the extensional voids, whether they’re merely tension gashes or more-developed full-fledged boudin necks.

Yes, I see: that example really does make the point in a spectacular way. I guess my only comment is that this example also shows a lot of “pull up” of the under–and over–lying laminae, for a considerable distance above and below the boudin necks, as would be expected in response to the tensional dilation. The greenstone/marble example (at least below the central boudin neck) seems to show no such upward convexity of the underlying bed contacts–in fact, slightly the opposite. I guess this could be accounted for by a rheological contrast between the light green marble (less viscous) and the white marble (more viscous) which could allow the green marble to flow up without affecting the “stiffer” white marble below. Dunno.

(Hmm…slightly off topic: looking now at the light green stuff below the central boudin neck, it seems that wispy brownish stringer in the middle of the light green marble is truncated against the base of the left-hand boudin. That’s interesting, too, and maybe speaks to a compromise between your and Jay Kaufman’s interpretations, as you suggested in the original post?)

Is that in the area of Carter’s Quarry? Are not the Fauquier Fm carbonates lying conformably beneath the Catoctin Formation flood basalts except for such boudinage or flame structures? Then perhaps what structural features you perceive are due to later tectonism? Or perhaps of a primary sedimentary/volcanic nature but reshaped by that later tectonism?

Yes, I think the abandoned quarry here must be the eponymous Carter’s Quarry.

Yes, I think the consensus is that, regionally, the contact is conformable. Flame structures would be consistent with that. Boudinage would presumably be a later (tectonic; Alleghanian) addition that overprints the original contact, conformable, unconformable, or otherwise.

Yes, I think that whatever was here originally (“of a primary sedimentary/volcanic nature”) was reshaped by later tectonism — the question is, how much, and how can we tell how much?