21 February 2013

Strained stylolites in Elkton East

Posted by Callan Bentley

Whoa – look at all that GREEN. You can tell this Virginia picture wasn’t taken recently. In fact, it’s another image from the field review I participated in for the Elkton East quadrangle back in May of last year. Somehow I start blogging these things, but run out of steam (or really more accurately: I get distracted by other stuff) before I finish.

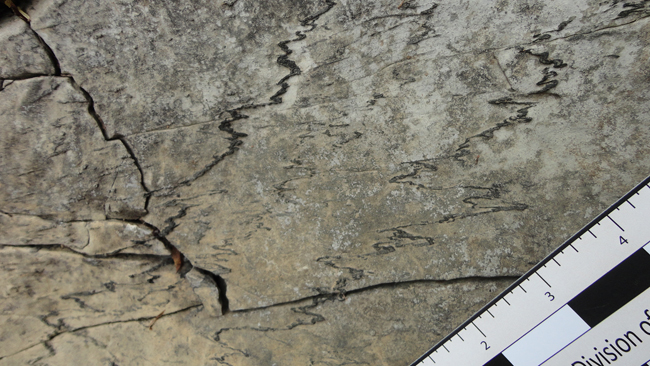

Today’s (I think, final) tidbit: sheared stylolites in Big Gem Park in the town of Shenandoah, Virginia (in Page County, not in Shenandoah County, as I’ve delineated previously):

Stylolites are structures that form due to pressure solution. In general, they form in a roughly planar geometry that is perpendicular to the σ1 direction, but that plane is actually very wiggly when you get down to it – it’s like a bed of nails, consisting of gazillions of spikes pointing in the σ1 direction. The “Tennessee Marble” (a skeletal limestone popular as a building stone in DC – the National Air & Space Museum is cloaked in it) is a classic example of this phenomenon: it shows stylolites more or less parallel to the bedding plane – and thus the gravitational force of compaction is likely responsible for their generation, rather than some horizontally-direction tectonic stress.

Anyhow – these Big Gem stylolites occur in the Stonehenge Formation at the base of the Beekmantown, where it overlies the Conococheague Formation. The stylolites are a different color (and offer a different resistance to weathering) than the rock from which they are derived because they are compositionally different. While the Stonehenge is a limestone with some clay scattered throughout it, the stylolites are the areas where the calcite (main constituent of the limestone) has been “squeezed out” by pressure solution, and the insoluble clays have accumulated as a residuum.

You can see they have a pronounced asymmetry:

The “peaks and valleys” of the stylolites are not perpendicular to the plane of the stylolite surface.

The interpretation for this observation is that they have been sheared, and that shearing is related to the Stanley Fault, which is drawn in near this location on the new map.

I know I mentioned Ernst Cloos’ work in this area, but did I also mention that the previous geologic map of this quad was developed by none other than P.B. King?

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Nice timing! Just today we were going over styolites in our Sed./Strat. lab.