24 March 2011

North Pole, South Pole, by Gillian Turner

Posted by Callan Bentley

I was sent a review copy of a new book about the Earth’s magnetism, and I finished reading it last week. It’s called North Pole, South Pole: The Epic Quest to Solve the Great Mystery of Earth’s Magnetism, and the author is Gillian Turner, a senior lecturer in physics and geophysics at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand.

I was sent a review copy of a new book about the Earth’s magnetism, and I finished reading it last week. It’s called North Pole, South Pole: The Epic Quest to Solve the Great Mystery of Earth’s Magnetism, and the author is Gillian Turner, a senior lecturer in physics and geophysics at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand.

Here’s a link to the book on Amazon.

It’s a book about the history of our understanding of magnetism, and specifically the magnetic field generated by the planet Earth. As such, it will be of interest to historians of science, geologists, and physicists. Turner’s job (which she is reputed to be quite good at) is to make science understandable, and she succeeds in this book of developing scientific ideas over time, and telling this evolutionary tale as a narrative story, with characters and context, insights and false leads. You hear how scientists like Ampère, Celsius, Faraday, Gauss, and Galvani all contributed to our growing understanding of the magnetic phenomenon, as well as luminaries like Ben Franklin and Pliny the Elder.

The magnetic field is a fascinating thing. Just watch:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgDYx3B8c_I]

Turner describes how early workers experimented with magnets, interested in magnetic induction via electricity, and the fact that when you break a magnet in half, the two halves act like miniature versions of the magnet they were derived from: they each have a north pole and a south pole.

All well and good, but the part that attracted (pun intended) my attention the most was the latter half of the book, wherein Turner describes the scientific story of how magnetism has catalyzed new geologic knowledge.

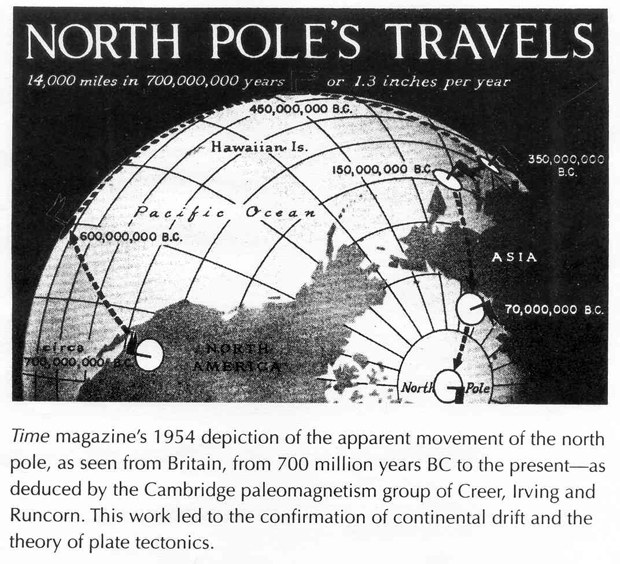

A key insight of pioneering geo-magneticists was the idea of the apparent polar wander path. This notion was that if you queried a stack of rocks from one place (say, the layers of lava flows on the side of a middle-aged volcano), and “asked” them where the North Pole was at the time they crystallized, the sequence of “answers” will indicate the apparent “wanderings” of the North Pole.

Here’s a charming image from a 1954 issue from Time magazine that Turner uses to simultaneously communicate the scientific idea of apparent polar wander (from the perspective of Britain), but also –thanks to the quaint style of the graphic– to communicate the time (1950’s) that this idea was germinating:

This was a critical insight for plate tectonic theory, as different continents (or indeed, different parts of the same continent) yielded different apparent polar wander paths. Imagine a a fleet of canoes, drifting on the sea near a light house erected on a rocky shoal. From one boat’s perspective, it might appear that the lighthouse is moving to “the right” over time. The occupants of a second canoe might report that the lighthouse appears to be moving to their left. A third boat still might report the lighthouse doesn’t shift laterally at all, but it is getting smaller over time, as they drift further away. Only by correlating these different perspectives do we realize that it’s not the lighthouse that is moving; it’s the boats! Similarly, the apparent polar wander path described by a particular continent’s rocks diverges from its neighbors as you go back in time. If the continents were to remain fixed in position, this would imply that the modern North Pole was once a dozen or more poles that only just now converged and coalesced in northern Canada. On the other hand, if the magnetic field is more or less constant in its structure, and the continents are the things that do most of the moving around, then that makes for a much more understandable geo-dipole shape, and implies continental drift, to boot!

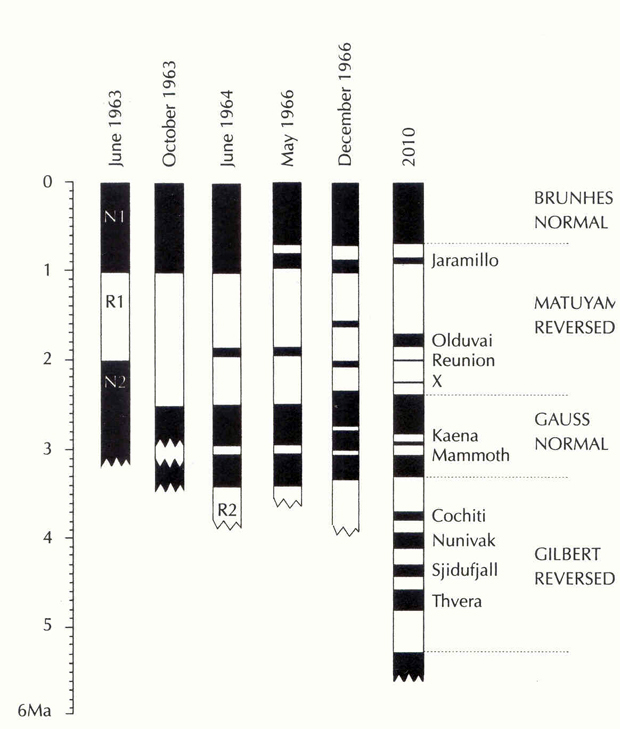

The book isn’t swimming in graphics, but there are a few other useful figures. Here’s another one that I was struck by — it shows scientists’ evolving understanding of the pattern of magnetic reversals over time, from the 1960s until today:

This is the evolution of a chronological record as surely as is the increasingly-fleshed-out stratigraphic column in the days of Sedgwick and Murchison. When I pause to consider a graphic like this that records the expansion of human knowledge, I get all swoony with the additive nature of our understanding. We know more now than we did before; we’ve got a better handle on this stuff. Do we have it all figured out? Nope. Do we make mistakes along the way? Quite assuredly. But over time, we sift the wheat from the chaff, and we get a chewier story, a more detailed perspective on our place in the cosmos.

Turner’s writing is solid and dependable, but without flourishes. It’s not McPhee or Winchester, but something more solid and reliable, lacking narrative indulgences. As such, it will appeal to some, and be deemed a tad on the dry side by others. It worked well enough for me — sufficiently engaging to power me through the book in short order, and thus allowing me to learn along the way.

Overall, I’m pleased to have read the book, and would recommend it to my peers in the geosciences.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

[…] American Geophysical Union’s Mountian Beltway blog reviews North Pole, South Pole by Gillian Turner. This entry was posted in News & Events. Bookmark […]