22 October 2015

Being objective (with yourself)

Posted by Jessica Ball

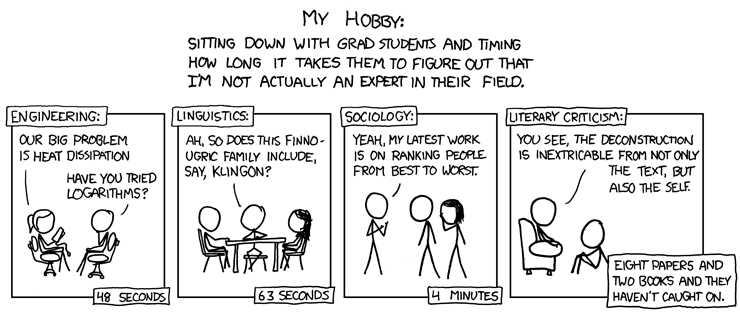

XKCD “Imposter”. I haven’t ever tried this, but I bet it could be fun at parties.

I recently recorded a podcast with Chris Jones of Rock Your Research (check out that website – he’s had some great guests on so far!) The very first question I got to answer about grad school was what I struggled the most with, and all those of you who’ve gone through grad school can probably guess that I said “impostor syndrome”.

I’ve written a little bit about it before, but it’s been biting me pretty hard lately. The kind of modeling I do can get really complicated and I spend a lot of time not just running the models, but justifying how I’m running them. Basically, on a bad day I feel like this amounts to “this is the best excuse I could find for NOT doing the thing the other way, because that way would be really hard”. But modelling is a tough field for someone dealing with the kind of anxiety I get, because there is no concrete dataset at the end of the model. It’s not like I’m dating something or doing a geochemical analysis. I can validate them to some extent, but it’s not like I can go out and do a pump test with an entire volcano, for example. Being a person who has perfectionist tendencies and impostor syndrome bites the big one, especially if you’re a modeller, because you’re never going to be able to unequivocally prove a model on a natural system.

Impostor syndrome also always pops up when I get reviews on something that I’ve written. Logically I know that the reviewers aren’t out to get me and that the comments are meant to be constructive, but my subconscious never seems to get that. I inevitably end up with that panicky, sick-to-your-stomach, oh-boy-I’m-in-big-trouble-feeling. (I was totally like this as a kid, too. Completely straight-laced, utterly paranoid about stepping out of line. It meant I got a reputation with my teachers as being the ‘responsible’ one, which is great in the long run but gets you labeled a teachers’ pet with your peers. Suffice to say I was never going to win any popularity contests…) Generally, I have to let a response email sit for a couple of hours after that initial panic moment, and I never read them while I’m at home – I basically just turn into a big ball of anxiety and I can’t concentrate on anything else.

I get anxious a lot. Maybe it doesn’t seem that way to people who only see me at work or meetings, but I guess that’s because I do a decent job at managing it. If I don’t, I can’t function well enough to get anything done, and then I spiral into feeling anxious about that and it’s all just one big angst-fest and I end up eating whole bars of chocolate and watching Firefly reruns. (This being the Bay Area, Ghirardelli is in ready supply, so at least it’s good chocolate.) The problem with getting mired in anxiety is that it’s really hard to take a step back and remind yourself that science is rarely as clean and pretty as it’s depicted in the media, movies or otherwise; it’s a long, difficult slog that’s often messy and doesn’t leave you with nice, neat answers. And, sometimes you fail. I want to do my very best not to fail, because I hate the thought that I might not get what I expect to out of my postdoc, but sometimes I have to face the fact that things don’t always turn out the way I expect them to.

On better days, I remember that unexpected results aren’t necessarily bad ones, and I remember that a negative result can still be valuable. It’s just that drawing interpretations from results you weren’t hoping for is a lot harder to do than tying up a nice, straightforward dataset that did behave the way you expected. And I try to remind myself that I model stuff for a living, and that’s a messy corner of geology where you spend a lot of time justifying what you’re doing and working around the simplifications necessary to get models to run. (And it takes a long time to publish the results. I’m on the second version of a paper from my PhD right now and boy, I hope the revisions push it through this time!)

I’m a smart person and I’ve known all these things for a while, but there’s a big divide between knowing something and really internalizing and accepting it. Being objective is relatively easy when it comes to dealing with data; it’s not so easy when you have to do it with yourself. But I’m going to keep trying, because at the bottom of it all I do love what I do, and I wouldn’t have come this far if I didn’t want to be doing it. So I’m going to keep running my models, and keep submitting revisions, and keep trying to write papers even when they get rejected, and just generally keep on slogging through the slow and messy process of science.

And, every once in a while, tell the voice of impostor syndrome to shut up and have some chocolate.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Maybe the best thing to do is give full disclosure on the model accuracy. This is the data I have, there may be some I don’t have. These are are the parameters I used but they could go from here to here depending on X.Y & Z. And so on. Instead of feeling like you need to deliver perfection, try to be perfectly clear about the limits of the data or model accuracy. Do the best you can, but don’t try to fool anyone about the limits of the model accuracy and the impossibility of testing the result. That should take the stress out of it.