13 January 2014

Benchmarking Time: Great Falls, Maryland

Posted by Jessica Ball

On the first day of the new year, I got completely stir-crazy and drove off for a hike. I wanted to see some bedrock, but because I live on the Virginia side of the Potomac River but not far enough west to be in the Piedmont province, we don’t have rocks to look at. (We have some lovely river terraces and a whole lot of cobbles of things that came from the parts of the Piedmont and Blue Ridge where they have rock exposure, but that just doesn’t count.) So I braved Northern Virginia traffic and a chunk of the Beltway to go visit Great Falls – specifically, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park on the Maryland side.

I wrote a post a while back on the hike that I took with Callan along the Billy Goat Trail on the Maryland Side of the Falls. As I mentioned there, Great Falls cuts into bedrock in the Piedmont province, mostly Lower Cambrian metagraywackes (that’s metamorphosed ‘dirty’ sandstone without the fancy terms). The ‘dirty’ part is actually clay in there with the quartz sand that formed the original sandstone; when it metamorphoses the clay becomes muscovite or biotite mica. The graywackes at Great Falls were deposited by turbidity currents in an ocean basin (you can see graded bedding sequences in some places), and during the Taconian orogeny they were smashed between the North American continent and an incoming volcanic island arc. (If you’d like the full history, go read Callan’s excellent “Geology of the Billy Goat Trail” handout.)

I didn’t have enough time for the Billy Goat Trail on this trip, so I took the Gold Mine Loop instead. It turned out to be a good decision, because almost no one was on it and I had the woods all to myself. “Gold Mine?” you might be saying. That’s right – there was a gold mine in the Great Falls area from 1867 to 1939. There are abundant quartz veins in the metagraywackes, and quartz veins are a good place to look for gold. It turns out that there were a number of such mines in the area (Montgomery County), although none of them have been in active production since the 1950s.

Here’s an example of some of the outcrop there, which had lovely quartz veins that were folded up in that continent/arc collision about 450 million years ago.

Lots of folds, with the remains of my manicure for scale. (Being a geologist, I am brutal on manicures and this one didn’t last long after I started poking around the outcrop.)

And, of course, the reason for the post: the marker I found along the way. (Actually, I was trying not to get stuck in the mud and I used it as a stepping stone initially – but it stood up to the abuse pretty well.)

This is a US Department of the Interior / National Park Service marker, probably meant to mark the trail. There are others in various spots around the canal, although those places were too busy to take photos!

After my quiet hike, I decided to walk a bit in the other direction and go see the Falls themselves. The water was quite vigorous at the bridge crossing to Olmsted Island, which is an example of a bedrock or river terrace forest (plant and animal communities that live with poor soil and periodic flooding).

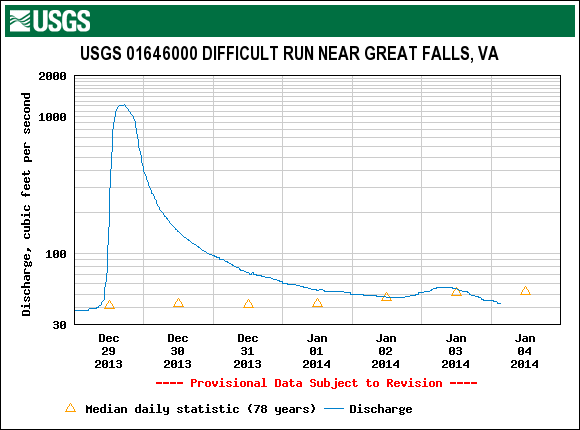

This is the closest stream gauge info I could find at Great Falls for the first week of the year:

So, despite appearances, not as high a discharge as it was on the 29th of December – in fact, not all that much above the median daily value. Still, I prefer to watch that kind of rough water from the walkways on Olmsted Island!

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.