3 July 2013

Another dispatch from the IVM-Fund: 2013 Guatemala Trip Report

Posted by Jessica Ball

(Note: All photos are courtesy of Jeff Witter unless otherwise noted.)

Any of you who’ve followed this blog for a while know that after doing my fieldwork in Guatemala, I worked with Dr. Jeff Witter to put his organization, the International Volcano Monitoring Fund (IVM-Fund), in touch with the fantastic folks at the Santiaguito Volcano Observatory and the Instituto Nacional de Sismología, Vulcanología, Meteorología e Hidrología (INSIVUMEH). Jeff’s organization is dedicated to supplying volcano observatories who lack funding with the tools to conduct critical volcano research and monitoring activities. After the initial introductions, my role has mainly been in a cheerleader, but I’m still always excited to see a new update about their activities. Jeff has been working in Guatemala for several years now, and what follows is summarized from his latest report on the IVM-Fund’s work with Guatemalan volcano observatories. (If you’d like to read the whole report and not just my paraphrasing, it’s posted on the IVM-Fund website.) And, as always, if you have the resources to donate to the IVM-Fund, they are always looking for new funding (even if it’s only a few dollars!) There are also some pretty spiffy t-shirts available to buy.

Two years ago, following the conclusion of the first program in Guatemala, the IVM-Fund asked Gustavo Chigna, Guatemala’s chief volcanologist, how it could further support volcano monitoring efforts in his country. He informed the Fund that an equipment support program at the Fuego Volcano Observatory (OVFGO) would greatly benefit the two volcano observers stationed there who are responsible for monitoring this active volcano. The program would be very similar to one that the IVM-Fund conducted in 2011 for the other volcano monitoring outpost in Guatemala, the Santiaguito Volcano Observatory (OVSAN). A new support program at Fuego volcano was easily justified because Fuego is one of Central America’s most active and dangerous volcanoes ‒ the most recent violent eruption occurred in September 2012, forcing the evacuation of thousands of Guatemalans.

It turned out that the volcano observers stationed at OVFGO were not only in need of their own set of tools to make measurements and record observations of volcanic activity but also wanted to establish OVFGO as a regional volcano education center. For example, they dreamed of presenting video footage of volcanic activity to audiences of school children, civic leaders, and government officials in order to demonstrate the wide array of volcanic hazards and what to do when faced with such hazards. This combination of active volcano monitoring and public safety education is exactly the type of program the IVM-Fund seeks to support.

The 2013 IVM-Fund/OVFGO team (from left to right): Amilcar Cardenas, Gustavo Chigna, Carlos, Charlie Vos, Edgar Barrios and two of his children, and Jeff Witter.

In 2012, the IVM-Fund raised sufficient funds to purchase all of the equipment Gustavo requested for OVFGO, and Jeff (together with Charlie Vos, the registered agent at the IVM-Fund’s U.S. headquarters in Seattle) made a trip in March of this year to hand-deliver all of the equipment to our Guatemalan partners and oversee its deployment at the observatory. They also planned on checking in at OVSAN to find out if the equipment donated in 2011 had been helpful to the observers, was still in use, and if any items were in need of replacement. Not only did Jeff bring supplies for the OVFGO observers, but he was able to deliver a donated part to repair a broken COSPEC (a tool for measuring volcanic gases, particularly sulfur dioxide). On the way down, much of the purchased equipment was held up in customs, but INSIVUMEH was able to speed the process and it was ready for pickup by the second day of the trip.

OVFGO (Fuego Volcano Observatory)

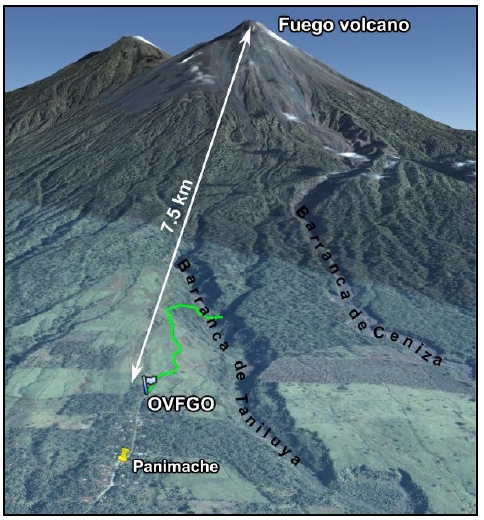

The Fuego volcano observatory on the edge of the community of Panimache and a typical view of Fuego from OVFGO with a small ash plume rising above the crater.

The team traveled first to the Fuego volcano observatory, which is is situated at the edge of the small town of Panimache on the southwest flank of the volcano only ~7.5 km from the active summit crater. By the evening of the second day, the OVFGO team had unpacked and set up all the new equipment, which included a new desktop computer, a GPS, a laser rangefinder, a temperature/pH meter, a digital camera and camcorder, and an infrared thermometer. The remainder of the visit to Fuego was spent testing the equipment in barrancas (river canyons) at the foot of the volcano. There are about 75 families living in the town of Panimache, but in this sector of the volcano, there are also several other villages, all within ~10 km of each other. The total population amounts to ~15,000 people. This entire SW sector is exposed to a number of volcanic hazards that vary in their degree of severity. Panimache itself is built on volcanic deposits laid down in previous eruptions of the volcano. In the event of a large eruption, evacuation of the community is the only option. Thus, astute observations and correct interpretation of the volcano’s behaviour, followed by effective communication between the observers and the community are key aspects to any decision of whether to recommend staying put or evacuating.

OVFGO observers Edgar Barrios and Amilcar Cardenas using the new GPS and laser rangefinder in the Barranca de Taniluya.

In addition to making visual observations of the magnitude of volcanic explosions and the direction of drifting volcanic ash clouds, an important part of the observer’s job is to document changes in the river canyons. The uppermost flanks of the volcano are constantly inundated with volcanic ash, accumulating from the near-continuous summit explosions as well as lava that pours down from the crater. These enormous quantities of volcanic material are sluiced down the river canyons during tropical downpours as cement-like flows of mud and debris called lahars. Lahars can be hot or cold, and can erode a river canyon to make it deeper and wider, causing canyon walls to collapse. Alternatively, lahars can also fill up a river canyon with mud and boulders such that any subsequent lahar or pyroclastic flow could overtop the banks of the river and inundate surrounding areas. Any of these situations created by lahars are undesirable. , However, it is possible to anticipate the potential impacts of lahars by making frequent measurements of the geometry (width, depth, etc.) of the canyons at multiple locations. The idea is to track where the great volumes of loose volcanic material are and attempt to predict where they will go in the next tropical rainstorm. The IVM-Fund has provided the OVFGO observers with the tools to make exactly these types of measurements.

Amilcar Cardenas documenting the Baranca de Taniluya with the new video camera. The cliff walls of the barranca are ~ 80 m high and very unstable, which contributes to lahars.

OVSAN (Santiaguito Volcano Observatory)

Jeff and his team made a grueling drive from Fuego to the Finca El Faro plantation (where the Santiaguito Volcano Observatory is located) to follow up on the IVM-Fund’s first volcano monitoring support program. In May 2011, they delivered ~$4000 worth of equipment to OVSAN for the purposes of monitoring the lahars, lava flows, and explosions that emanate from the Santaiguito lava dome complex. It was clear that the equipment was being put to good use, but Jeff also wanted to find out whether some of the instruments were more useful than others, if any of it needed replacing or repair, and if the observers had discovered that they needed additional tools to better perform their job of volcanic surveillance. Gustavo Chigna had also requested a large computer monitor to help OVSAN share video footage and photos with visitors to the Santiaguito observatory, which is used as a base by multiple university groups who are doing work at Santiaguito.

The team met up with Julio Cornejo (who was instrumental in helping me collect data for my thesis! – Jessica) and Alvaro Rojas, the two OVSAN observers, and headed up the stone roads of the Finca El Faro to the “Mirador” – an ideal vantage point for viewing the Santiaguito lava dome. There are currently five active lava flows descending from the summit of the lava dome, and in 2012 one of these lava flows overtopped a ridge and slowly poured down into the upper reaches of the Rio Nima I river valley. Up until that time, this river valley had not been significantly impacted by lahars, but this new lava flowing down the Rio Nima I is a new source of loose material to generate lahars. Julio and Alvaro have been documenting the advance of this lava flow and the impacts on this formerly jungle-clad valley, and based upon their measurements of the lava flow (using the instruments provided by the IVM-Fund in 2011) they estimate a volume of ~3 million cubic meters for this single lava flow. They have also estimated that the lava flow front advances at a rate of ~1.5 m/day during slow phases to up to 6-15 m/day during particularly active periods. During these periods of rapid lava advance, Julio and Alvaro also documented pyroclastic flows generated from the collapse of the lava flow front.

New lava flowing down the southeast flank of Santiaguito volcano. Photos taken from the Mirador in May 2011 (left) and March 2013 (right).

This lava flow has descended far enough to partially block the flow of the Rio Nima I. A small dam has been created and this is of some concern because during the next rainy season the impounded water could overtop the lava dam and flood downstream. Alternatively, continued advance of the lava could build an even larger dam which could potentially back up the water so far that it might begin to flow down a different drainage and flood the adjacent river valley of the Rio San Jose. Both the Rio Nima I and the Rio San Jose river valleys flow through pristine jungle and the coffee plantation.

View of the Upper Rio Nima I drainage before and after lava inundation. By October 2012 (left), the forest on the river banks had been destroyed by pyroclastic surges generated from collapses of the approaching lava flow front. By January 2013, the lava had overtaken that portion of the river valley. Both views look toward the northeast. Photos courtesy of INSIVUMEH-OVSAN.

There is no stopping the advance of this lava flow into the Rio Nima I drainage. A certain amount of lahar impact downstream is inevitable. However, the most important questions now are: Which river valleys will be impacted and to what extent? Will the lahars generally be proportional in size to the magnitude of the wet season rains? Or will a catastrophic flood be unleashed when the lava dam is breached? Seeking answers to these questions is the responsibility of the OVSAN observers. Making observations and measurements to provide advance warning of the type and severity of lahar activity is their task. The equipment provided to them by the IVM-Fund helps them in this endeavor.

On this trip, Jeff consulted with Gustavo to find out how else the IVM-Fund could support volcano monitoring efforts in Guatemala. Possibilities include:

- Continuous, online video surveillance of Fuego and Santiaguito volcanoes using webcams.

- An audible volcano alarm system at OVFGO to alert the community in case of emergency.

- Repair and maintenance of existing volcanic gas monitoring stations at Fuego and Santiaguito volcanoes. These could be an important volcano monitoring tool.

- Geographical Information System (GIS) software training for the observers at OVSAN and OVFGO to record, in a quantitative, map-based format, all the measurements and observations made by the observers. This valuable information could be used for the creation and updating of volcanic hazard maps.

- Equipment and training support for the new volcano observatory at Pacaya volcano, the third most active volcano in Guatemala.

These are things that many volcano observatories simply take for granted, but it’s a different story for the Guatemalan observatories, and that’s why the IVM-Fund’s work is so important. Supporting volcano monitoring efforts in Guatemala would not only contribute to the science of volcano monitoring, but would also have a positive public safety impact on the communities near these three active volcanoes. So I’m reiterating my plea: please help the IVM-Fund continue to support volcano monitoring in Guatemala and other countries!

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Well, you convinced me! I just donated a few dollars :-).

What does Magma cum laude mean? I find your blog fascinating. I found it while seaching Geology.com.

Thanks.

Keith

It’s a play on “Magna Cum Laude”, which is used to say that you’ve graduated with high honors.