27 February 2011

Geology and rock climbing

Posted by Jessica Ball

As a novice rock climber who’s also a geologist, I’m just as interested in the rock I’m climbing as the route. The type of rock you’re climbing on can have big impacts on the difficulty of the climb, since the way that a rock weathers and erodes determines what kinds of holds are available, whether there are cracks or ledges, vertical faces or overhangs, and what safety concerns you should be aware of. I haven’t had a huge amount of experience with outdoor climbing, but from the scrambling I’ve done on mapping excursions, I certainly know which rocks I prefer to climb on – but what do more experienced climbers prefer?

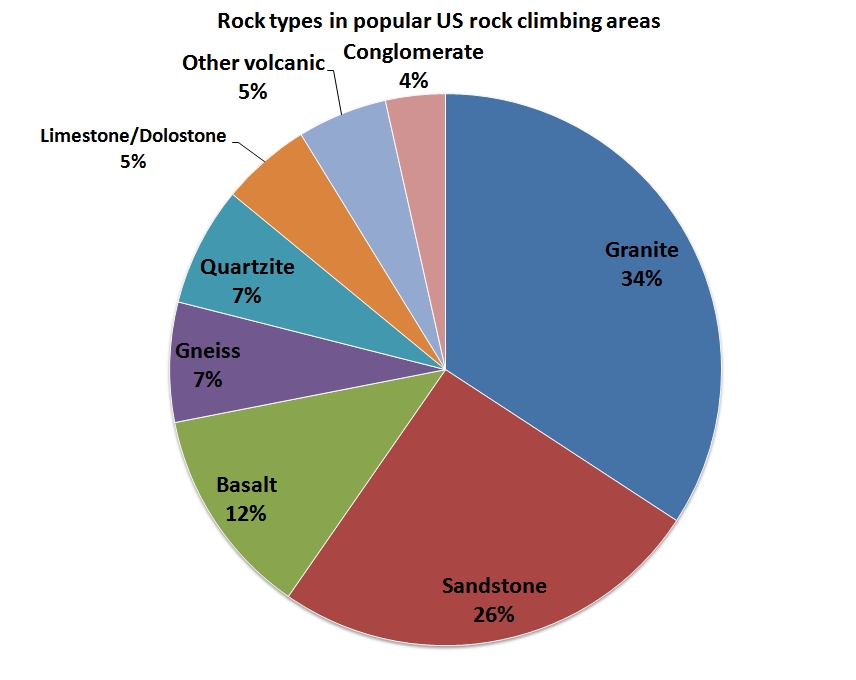

Most rock climbing guides don’t focus on the rock type as much as the features that make the rocks good for climbing, so I had to do a little research on my own. Out 118 popular US climbing areas listed on Wikipedia, a survey of rock types gives an interesting – but not terribly surprising – distribution. (If I have more time in the future, I’ll try to compile a worldwide list, but this will do for now…)

This is a pretty rough summary, and probably error-prone (and limited by Wikipedia’s list), but it’s possible to make some generalizations. Granite and sandstone are by far the most popular rock types, with basalt in third. This makes sense to me, when I think about it from a climbing perspective; granite, sandstone and basalt can all be pretty tough rocks – which means a hold won’t break off under your hands or feet – and they’re often rough, which provides friction for gripping. Limestone and dolostone are easier to dissolve and may have more “features” to grip, but this can also make them too weak for climbing. The metamorphic rocks are more of a mixed bag; quartzite is tough but also hard on the hands, while gneiss may have planes of weakness that make driving in climbing anchors chancy.

I don’t consider myself a climbing expert by any means, so I checked to see what the authors of my climbing books had to say about different rock types:

“Granite, basalt and sandstone are three types of rock that often have cracks…Sport climbing (bolt-protected face climbs on vertical or overhanging rock) is popular on limestone, sandstone and volcanic rocks” (Woman’s Guide: Climbing)

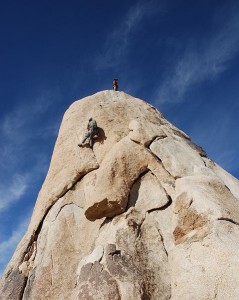

Climbers at Joshua Tree National Park, CA. © Jarek Tuszynski / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 & GDFL , via Wikimedia Commons

“Granite climbing is characterized by steep slab climbing (often lacking natural protection)…Rhyolite provides some of the very best and most highly featured rocks for climbing…Sandstone grains provide good traction and the rock is often fractured, providing natural protection placements…Water-solution pockets in limestone provide excellent hand- and finger-holds…Conglomerates can have surprising and excellent holds even on overhanging walls, but natural protection is usually unreliable….Quartzite often provides fantastic climbing and reasonable natural protection…Gneiss is a rough rock that can form large cliffs of variable quality…Slate can provide exciting climbing on tiny edges, often devoid of reliable protection. Even drilled bolts are of dubious value.” (The Climbing Handbook)

Weathering and erosion processes can be a mixed blessing when it comes to climbing. Exfoliation in granites, for example, forms cracks and other features which make ascent possible on huge cliff faces like the ones at Yosemite, but it can also create dangerously loose rock that can fall off in huge chunks. Dissolution in carbonates can form pockets that make great hand- and foot-holds, but too much dissolution can weaken the rock too much to support someone’s weight. And persistently wet conditions can basically turn a rock into clayey mush – probably a good reason that many popular rock climbing areas are located in more arid regions.

If there are any climbers out there reading this, what are your favorite climbing locations and rock types? Where do you find the most challenging climbs – or the easiest? Do you ever notice things like grain or crystal size while you’re climbing, and what effect do they have on your climbing?

References:

Long, Steve, 2007. The Climbing Handbook: The complete guide to safe and exciting rock climbing. Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY, 192 pp.

Presson, Shelley, 2000. A Ragged Mountain Press Woman’s Guide: Climbing. Ragged Mountain Press, Camden, ME, 176 pp.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Granodiorite grading to diorite is almost exclusively what I’m experienced in, though that’s not surprising given I live within the Coast Range batholith. I’m actually more used to ice climbing, but I guess that’s for another post

I’ve done conglomerate before within BC’s interior, and ages ago in New York’s Shawanjunk(sp?), and boy was that a fun experience. Your anchor is only as good as the fine matrix and its induration.

When I was a mere sprat, learning to rock climb in the Cascades, I learned my first geology lesson. There are two kinds of rock. ‘Good for climbing’, ‘Not good for climbing’ [but we climbed on it anyway].

In Washington State, we talk about ‘Oregon Rock’, which was cnsidered uniformly ‘not good for climbing’. We would refer to ‘Oregon hand holds’- find one you like, take it with you all day.

Dave Tucker

Another great climbing/geology reference is “Flakes, Jugs, and Splitters: A Rock Climber’s Guide to Geology” by Sarah Garlick. Sarah has a geology background, and talks about the rock at many famous climbing locales.

In order to determine what is the favorites of climbers, you need to normalize to the total available cliff face area of each type of rock available for climbing. II suspect that the most popular rock types shown here are simply the ones which form most of the climbable surfaces.

Also, I’m disappointed that nobody nominated serpentinite.

Thanks for sharing this–my own interest in rock climbing was a factor in my choosing to study geology all those years ago, as I wanted to know more about what I was climbing. Alas, why many years have elapsed I am still only a novice rock climber, having not put in near as many hours on such adventures as I have my studies…

count me in with the granite and sandstone, but then as everyone has pointed out, that is what is nearby

Limestone! Definitely. And I am sure that most of my friends will agree. But they all use to climb in (southern) Europe: Spain, France, Greece. There’s plenty of limestone, but you really have to search for good granite. I think limestone has the big advantage that it offers all difficulties due to its manifold of karst features. You can have an overhanging 8a next to a vertical 5c. And it’s so beautiful, white limestone in a tiny southern France valley in the sunset…

What Lab Lemming said. I climb sandstone because it’s here, and I suspect it’s “here” in a lot of heres.

I’ll bet granite and rhyolite are truly popular. The friction is unbelievable.

As for serpentinite, it’s also here and nobody climbs that stuff – way too brittle, doesn’t even make decent-size outcrops.

Great idea for a post!

I haven’t climbed outdoors in forever, but my favorite place was Castle Hill in NZ (http://www.basealpine.com/history_geology.html) which was a bunch of picturesque limestone boulders. When I took rock climbing I and II at W&M, our field trips were to Little Stony Man cliffs in SNP, which I believe was greenstone- you probably know better!

A book on geology, mill walking and climbing from the UK:

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=LUXW-sv5BTsC&pg=PA82&dq=book+UK+geology+and+rock+climbing&hl=en&ei=PhyWTdzmOYWa8QO19r0X&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CFAQ6AEwBTgK#v=onepage&q&f=false

Doh! Make that hill walking … Need more coffee!

Thanks for the interesting post. I’ve lived near two areas with vertical rock (Door County, WI and south-central NM) and both have fairly bad, dangerous rock to climb, so I was just interested to know what proportion of rock faces you see can actually be climbed safely. Is it just a small proportion of rock faces?

I would say it depends heavily on both the rock type and the state of that particular rock unit. If you were in a desert area with a lot of granite or sandstone, for instance, the percentage would probably be a lot higher than someplace with a lot of crumbly limestone. It also depends on how the rock has been fractured or weathered, and what the climate is like. So, no easy answer there!

Thanks, Jessica. I’m sure you’re right. The Door County dolostone is close to a worst case scenario, with a lot of water, a lot of freeze-thaw fracturing, and giant glaciers grinding the rock up every so often!

thanks for this article Jessica! Do you have others about geology and rock climbing?

No, none as of yet, but I hear that there’s a pretty good book out called “Flakes, Jugs and Splitters: A Rock Climber’s Guide to Geology” that talks about it. It’s written by a geologist, and it looks like she has a lot more experience on the climbing end than I do!