9 December 2008

Saving landslide victims

Posted by Dave Petley

In the last few days there have been two landslides that have led to searches in the hope of finding buried victims. The higher profile slide was this one that occurred in the Bukit Antarabangsa suburb of Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia) on Saturday (pictures from The Star):

This landslide, which has dominated the news in Malaysia over the last few days, killed four people and injured a further 15. One person is reported to still be missing – searches are continuing for her.

The other slide happened in Papua New Guinea when a slope above a camp at a goldmine collapsed, burying ten people. The Australian Government dispatched a search and rescue team, but no victims were recovered alive.

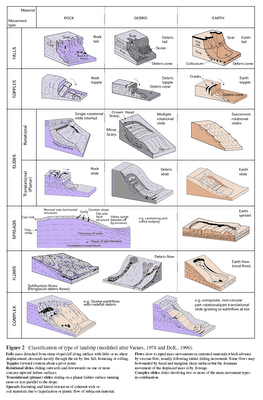

These two events set me thinking about how we go about recovering people who have been affected by landslides. As far as I know there has yet to be a proper scientific study of how and why people survive landslides and of where we should look for victims. This is a crucial shortcoming that urgently needs to be corrected. The key must be the type of landslide that has occurred. So lets start with our basic landslide classification (this diagram, from the Geonet web site, is pretty much the best that is available – click on the image for a better view):

So let’s look at these one by one:

So let’s look at these one by one:

1. Falls

All falls basically involve free movement through the air, meaning that objects at the toe of the slope are likely to be buried. Therefore, if the likely victims were located at the toe of the slope then the victims are likely to be under the rubble. This is what we usually see with rockfalls on roads for example:

Image from www.cbc.ca

Image from www.cbc.caHowever, away from the toe of the slope movement is often parallel to the ground surface, meaning that objects in the way get pushed outwards. Hence, vehicles away from the toe of the slope often get pushed off the road rather than buried:

In many cases, on roads this results in vehicles ending up in the river. For buildings this means that structures close to the toe of the slope will be buried, whereas those further away will be pushed outwards and usually collapsed.

In many cases, on roads this results in vehicles ending up in the river. For buildings this means that structures close to the toe of the slope will be buried, whereas those further away will be pushed outwards and usually collapsed.

2. Topples

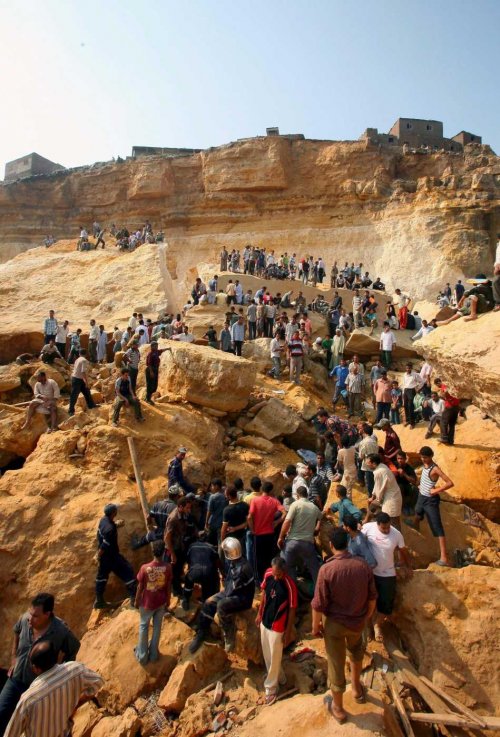

Topples on the other hand rarely have any substantial horizontal component to their movement. Therefore, in a toppling failure the victims are likely to be buried under the rubble. This was illustrated by the recent Manshiet Nasser failure in Cairo:

Here, almost all of the buildings were buried beneath huge boulders. Unsurprisingly, few people were recovered alive. However, in the case of topples buildings may at least partially survive and there are often gaps between the boulders, which means that there is a real possibility of recovering victims if search operations are undertaken quickly and efficiently.

Here, almost all of the buildings were buried beneath huge boulders. Unsurprisingly, few people were recovered alive. However, in the case of topples buildings may at least partially survive and there are often gaps between the boulders, which means that there is a real possibility of recovering victims if search operations are undertaken quickly and efficiently.

3. Slides

In the case of slides the key issues are:

- The location of the victims at the start of movement;

- The rate of movement;

- The distance moved; and

- The degree to which the slide breaks up.

There is a fundamental difference between the impact of the event if the victim is on the slide body rather than in its path. If the victim is on the top of the slide then the survival rate is probably quite high, even for long and reasonably fast events. In fact the Malaysia slide shows this quite well – structures on the surface are recognisable at the end of the event:

Of course there is usually a huge amount of internal movement of the landslide body, so buildings will often collapse. Thus, there is a real danger that people will be killed or injured in buildings, as above. Even in very fast and turbulent slides people sometimes survive on the surface. Below is the Hattian Bala landslide that was triggered by the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir. Two women who were cutting grass near to the crown (top) of the slide walked off unhurt at the bottom:

At the toe of the slide, objects in the way are hit and may be buried. Interestingly, in general it seems that in most cases structures are pushed outwards by the slide rather than being incorporated within it. Therefore, victims are likely to be found in the arc at or near to the toe rather than where the building originally was located:

Inevitably the level of damage to structures, and the survivability in general, is dependent upon the rate of movement and the distance that the landslide (and the victim) travels. Faster landslides moving longer distances have a far higher chance of killing the victim.

4. Spreads

Spreads are generally low velocity and therefore unlikely to kill, although buildings can and do collapse. The exception is in earthquakes, when spreads can be quite rapid and very large. Collapse of structures is the greatest hazard.

5. Flows

As with slides, flows depend on the location of the victim and the rate of movement. In this case, people on the surface when movement starts are far less likely to survive as the turbulence of the movement means that they can easily be drawn into the slide. Structures are likely to collapse completely. A mistake that is sometimes made is to look for buildings in their original location, whereas in fact they are likely to have been displaced a considerable distance. The best advice to rescuers is to look for debris as an indicator of the location of survivors

Image from Monsters and Critics

Image from Monsters and Critics The survival of structures in the way of a debris flow depends on the speed and size of the flow, and on the properties of the material that forms it. Unprotected people stand very little chance is the flow is anything other than small, but well-built structures are surprisingly resilient:

Image from USGS

Image from USGSHowever, larger flows and those with a high proportion of soil and rock, are very destructive:

Here the key is took for the location of debris from structures that might contain survivors. For weaker buildings this is unlikely to be in the location of the original structure. There is some evidence that the flow pushes debris ahead of it, at least for a short distance, so looking around the toe of the slide might be a good option, as was the case for the second La Conchita landslide:

Here the key is took for the location of debris from structures that might contain survivors. For weaker buildings this is unlikely to be in the location of the original structure. There is some evidence that the flow pushes debris ahead of it, at least for a short distance, so looking around the toe of the slide might be a good option, as was the case for the second La Conchita landslide:

Image from the New York Times

Image from the New York TimesThe danger to rescuers

Landslides often occur in stages. Therefore, there is a very real danger to rescue staff that they might be affected by another event. This story, from Taiwan last week, is a graphic illustration of this issue:

“The body of a worker who was buried in dirt from landslides at a landfill construction site in the central city of Taichung for more than 10 hours was recovered late Sunday after many twists and turns, city officials said. Wu Cheng-wei showed no vital signs when his body was pulled out of dirt at 11 p.m., and he was pronounced death on arrival (DOA) after being rushed to nearby Taichung Veterans General Hospital. Wu was the first to be buried in a series of landslides at the suburban site where a landfill retaining wall reinforcement project was underway, but he was the last to be recovered from the dirt because subsequent landslides claimed another victim and injured two municipal Fire Department staff members. Wu was buried when the first landslide hit at around 9 a.m. Sunday. The city government’s Fire Department dispatched a rescue team immediately after it received a distress call. While Fire Department staff and volunteers were busy searching for Wu, there was a second landslide which buried Fu Chia-sen, a volunteer firefighter. Fu’s colleagues then rushed to mount a new search mission. At around 1 p.m., two Fire Department staff members, identified as Lin Hung-yi and Chen Chieh-chi, spotted part of Fu’s clothing and tried to pull him out. However, another landslide hit, causing the pair to sink into the soft dirt. Lin Hung-yi was rescued first and was sent to the nearby Taichung Veterans General Hospital, where it was found that he had sustained only slight injuries. Chen Chieh-chi, who was buried in dirt from his chest down, was not rescued until around 5 p.m. He complained of acute pain in his legs and was sent to hospital for examination and treatment of his injuries. Fu Chia-sen was also pulled out of the dirt at 5: 35 p.m., but he showed no vital signs. He was pronounced DOA after being sent to the hospital.”

Summary

I guess my take-home messages

are:

- We really need to look at this issue properly!

- The type of landslide determines how, where and why people might survive. Therefore, getting someone who knows about landslides, and about landslide rescues, involved at an early stage is critical;

- There is also a need to protect the rescuers against further landslides. A landslide specialist can help in this;

- If in doubt, look for the location of debris from buildings. This is most likely to tell you where the victims are.

I would welcome any comments or thoughts on this. Has anyone any experience to share?

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

I recently came across your blog and have been reading along. I thought I would leave my first comment. I don’t know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog. I will keep visiting this blog very often.Sharonhttp://www.autoloans101.info

I recently came across your blog and have been reading along. I thought I would leave my first comment. I don’t know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog. I will keep visiting this blog very often.Sharonhttp://www.autoloans101.info

Malaysia was also hit by a couple of landslides before the big one at Bukit Antarabangsa. These are within a week. 30th Nov Ulu Yam, 2nd Dec Jln Semantan. 6th Dec Bukit Antarabangsa.This one at Ulu Yam in Selangor is quite major as it claimed 2 young lives.http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2008/12/2/nation/2696149&sec;=nationThis one at Jalan Semantan in KL was more of an earth retaining structure failure.http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2008/12/5/nation/2729794&sec;=nation

1. To identify the position of missing person2. To clarify the criteria(s) for emergency evacuation for rescuers1 is not so easy in the case of debris flow. The broken material of house and car, may be a sign of position where people might be. In the case of walking people, it is almost impossible to identify their locations. I think we may change our way of thinking in such case to “look for a void where people can survive” which may be equal to look for a area of not-so-muddy though it is still difficult during the rainfall.2 is also a problem. Landslide experts may play a role in this field but they tend to find a symptom which seems a sign of secondary slide at that time but does not lead to the secondary slide finally. During a rescue activity in a surfacial slope failure, I found an increase of discharge of groundwater from failed slope and advised to rescuers to evacuate. However, the slope is still stable after 6 months except for limited number of rock falls and very small failure. I wonder the criteria for emergency evacuation may be based on “the initiation of sliding” rather than “symptom of sliding”, which will provide the rescuers very short time for evacuation.

I recently(middle of July 09) came across your blog and have been reading along. I am doing my masters in geography. In july i got struck by three land slides in Kerala, state of India. The next day I searched for some one who is really interested in the topic…I have few photos of those incident I am happy to share those with you.Thank you.

Dear SaneeshThat sounds very interesting – yes please. Please can you email me at [email protected] wishes,Dave

I'm one of your many landslide-researcher/lurkers.I'm writing a paper where I'd like to include a comment about how models which ignoring internal complexity but matching external behaviour are great for runout analysis and forward prediction, but not so hot for modelling events for search-and-rescue. This entry is the first place I'd encountered that idea, and I'd like to give credit but referencing a blog isn't exactly acceptable for journals! Have you expressed a similar idea somewhere more formally since you wrote this?