10 December 2019

Property values plummeted and stayed down after Hurricane Ike

Posted by sedwards

Study points to solutions that could protect residents in at-risk neighborhoods

By Jonathan Wosen

A home elevated above ground level in Houston, Texas to protect against flooding. Many homes in Houston are now built or rebuilt on beams that elevate them 10 to 12 feet above ground level. Credit: Antonia Sebastian.

Texas homes that took the biggest hit in value after 2008’s Hurricane Ike were, surprisingly, not those within historic flood zones, new research finds. Instead, they were homes just outside these zones, where damage affected whole neighborhoods, driving property value down for years, according to a team of researchers from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill who presented the findings this week at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2019 in San Francisco.

The findings help researchers identify which homeowners are most likely to default on their mortgage after a major storm — and to devise solutions that protect homeowners.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency defines 100-year flood zones as areas where there is a 1% or greater chance of flood in a given year. But flood waters can spread well beyond these zones in many urban areas, where water flows freely over broad swaths of concrete, according to Harrison Zeff, engineer at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and member of the team that presented the new findings.

That’s a problem, because while federal law requires residents in 100-year flood zones to purchase flood insurance, there’s no such requirement for those outside these zones. So when a storm hits and residents have to foot the bill for damages, they often end up borrowing money against the value of their homes. But residents already saddled with mortgage debt might cut their losses and leave altogether, according to Zeff.

“A lot of people either try to sell their homes for bottom-dollar price to pay off their mortgage, or just walk away, defaulting on the mortgage,” Zeff said.

That happened after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. As of 2017, at least 20,000 buildings remained abandoned in New Orleans.

In the new study, Zeff and his colleagues wanted to understand the forces that send home values crashing after a storm. They used data from First Street Foundation, a New York-based flood risk nonprofit, to study property values in Harrison County, Texas from 2006-2014. The county includes Houston, which was hit hard by Hurricane Ike in 2008.

The researchers combined the property value data with on-the-ground observations by local officials on which homes were damaged. They found damaged homes within the flood zone lost value after the storm but, on average, recovered most of their value by 2014. In contrast, most homes outside the flood zones hadn’t recovered their value by 2014.

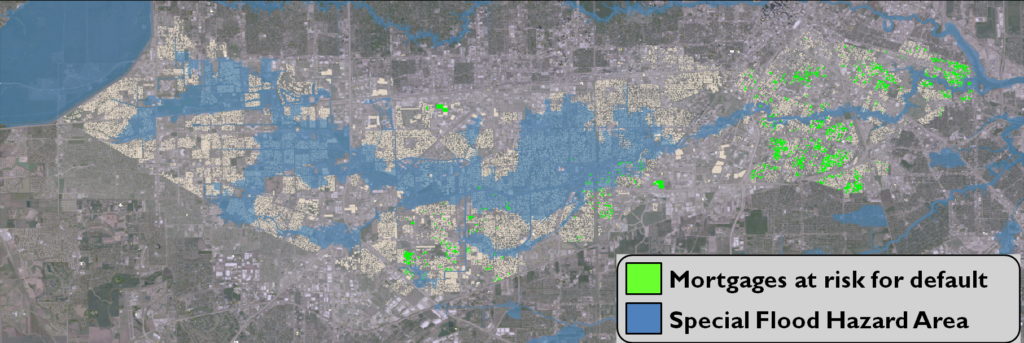

A map of neighborhoods in Houston’s Brays Bayou with increased mortgage default risk due to flooding damages after Hurricane Ike, compared to the special flood hazard area. Many homes with increased risk are outside of the hazard area. Credit: Harrison Zeff.

To understand why homes outside the flood zone took a bigger hit, the scientists looked at the relationship between property value and how many nearby homes had also been damaged. They found homes in communities where neighboring houses had also been damaged lost the most property value. In areas with 200 or more damaged homes per square mile, the average home lost a third or more of its value.

The finding suggests one of the main reasons homes outside flood zones lose property value is because neighboring homes are in the same predicament.

“If every home on a block is up for sale, that’s going to do something to the value of those homes,” Zeff said. “There’s now this glut of homes that were damaged.”

At least some of those affected by Hurricane Ike were Hurricane Katrina survivors who fled to Texas. Since then, Texas has had floods in 2015, 2016 and was hit by Hurricane Harvey in 2017 — meaning that some unlucky homeowners have been hit by multiple storms. The researchers’ next step is to extend their analysis to 2019 to include these more recent storms. Zeff expects that property values will have plummeted even further in areas battered by storm after storm.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. The findings suggest expanding the same protections found within flood zones could help those outside of them.

“Urban planners, city managers, and insurance companies can … apply different policies in order to control these trends and help them to protect the environment,” said Mona Hemmati, doctoral student in civil and environmental engineering at Colorado State University, who was not involved in the new study.

Such solutions include expanding flood insurance coverage, improving storm drainage systems, elevating homes and building parks so that storm waters seep into soil rather than running across concrete.

—Jonathan Wosen is a current student in the UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program. You can follow him on twitter at @JonathanWosen

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

First Street Foundation is a nonprofit. There is a typo in the article calling the Foundation a “profit.”

Hi Carolyn, thank you for catching this mistake. It has been corrected.