14 August 2019

Unprecedented 2018 Bering Sea ice loss repeated in 2019

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

A lone Arctic sea ice floe, observed during the Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project in October 2014. Credit: NASA/Alek Petty.

By Theo Stein

Sea ice in the Bering Sea reached record-low levels during winter 2018, thanks to persistent warm southerly winds. These conditions caused the ice to retreat to the northern reaches of the 800,000 square mile body of water.

Scientists were amazed. “It was about half of what we usually have in winter,” said Phyllis Stabeno, an oceanographer at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle and lead author of a new study in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters detailing the event. “To be blunt, all of us were shocked. This isn’t how it’s supposed to work.”

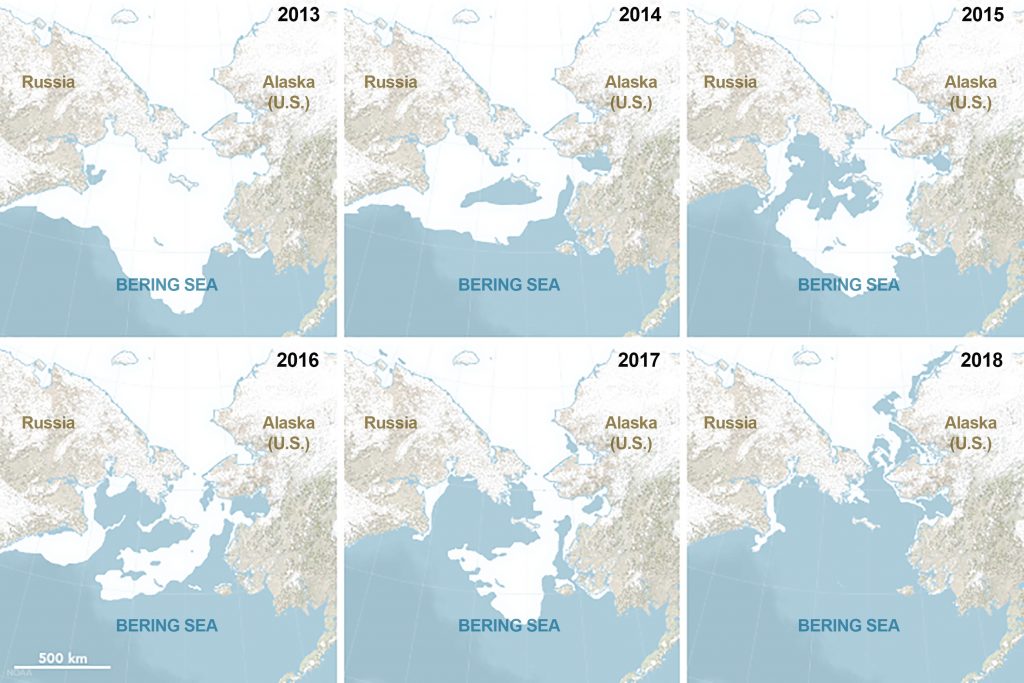

At the end of April 2018, Bering Sea ice covered 61,704 square kilometers (24,000 square miles). By contrast, sea ice extent on April 29, 2013, was 679,606 square kilometers (263,000 square miles), closer to the 1981 to 2010 average. By the end of April 2018, sea ice was about 10 percent of normal.

And then, much to the scientists’ surprise, 2019 just missed eclipsing the record set in 2018.

In the past, cycles of cold years with extensive sea ice would be succeeded by warm years with less sea ice, Stabeno explained. Climate models have predicted these warm, ice-eating winter winds would become common in the 2030s. “We did not expect to see these low-ice conditions for at least 10 to 15 years,” she said.

Scientists are now wondering if another cold cycle will recur, or if the Bering Sea has passed a tipping point. Complicating matters is the ongoing melt of the Chukchi Sea, to the north of the Bering Strait separating Alaska from Russia. Ice in the Bering Sea forms when cold winds over the Chukchi Sea come blasting down from the north.

Using data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center, this time series shows the maximum ice extent in the Bering Sea during April for the years 2013 through 2018. The year 2018 set the record for the least amount of sea ice dating back to 1850.

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens.

“To get the frigid winds out of the north that freeze the Bering Sea, you have to freeze the Chukchi,” Stabeno said. “But now the Chukchi is not freezing until December. That means there’s less time for the Bering to freeze up.” Still, Stabeno isn’t ready to go out on a limb and predict that Bering Sea ice is history. She’s seen too much variability over her 30 years of research.

“There’s always year-to-year variability,” said Rick Thoman, Alaska climate specialist with the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who was not connected to the new study. “But these kinds of winters are going to become more and more common.”

What does this mean for the ecosystem and Alaska? The Bering Sea is one of the largest and most valuable fisheries in the world, contributing about half of the nation’s fish landings. The current distribution of fish stocks is dependent on a cold pool of water at the bottom of the shallow sea. Species like Arctic cod thrive in colder water, while the shift of just a couple of degrees allows Pacific species like pollock to replace Arctic cod. “This has tremendous implications for the ecosystem,” Stabeno said.

The conditions associated with warmer winters would disrupt not only the marine ecosystem but the conditions that generations of Alaskans have come to depend on. Sea ice dampens waves, making fishing safer. Subsistence hunters need ice to pursue seals and whales. Open water allows waves to hammer the coast, eroding beaches and threatening towns.

Stabeno has mixed emotions at watching the impact of climate change unfold before her eyes. “As a scientist, it’s fascinating to see our predictions coming true,” she said. “As a human being, it’s not so good.”

—Theo Stein is a Public Affairs Officer with NOAA Communications in Boulder, Colorado. This post originally appeared as a news story on the NOAA website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.