20 December 2018

Northern Hemisphere heat waves covering more area than before

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

By Hannah Hagemann

Heat waves in the Northern Hemisphere have gotten more expansive in recent decades, covering 25 percent more area now than they did in the 1980s, according to new research.

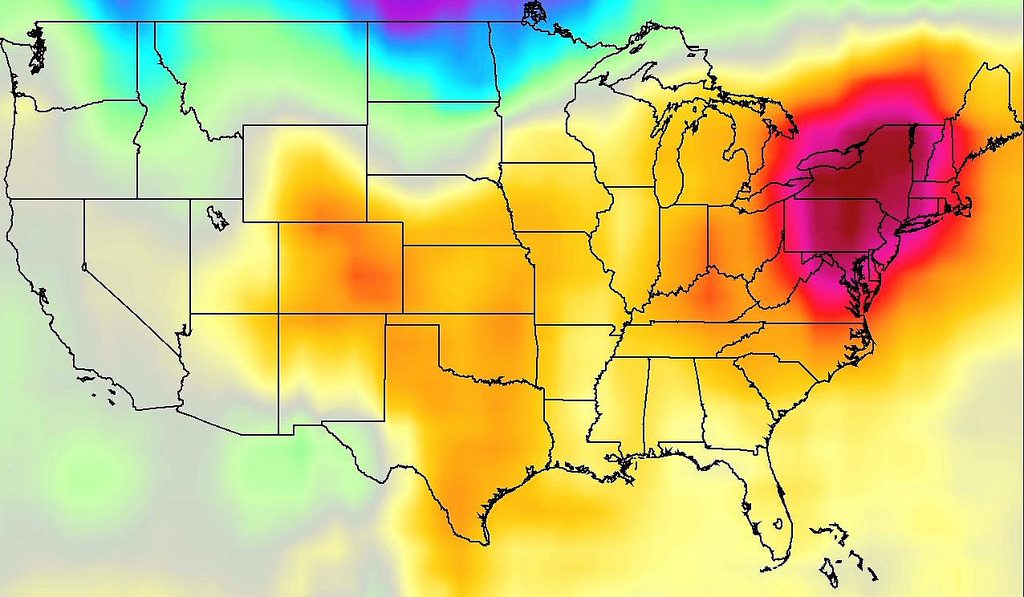

The heat wave in the United States in July 2011 broke temperature records in many locations, killed dozens and put nearly half of all Americans under heat advisories at its peak.

Credit: NASA/JPL AIRS Project.

A team of researchers from the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, University of Delaware and Stanford analyzed 38 years of NASA climate and weather data and found the average size of a heat wave has grown by 50 percent over the entire Northern Hemisphere and 25 percent over Northern Hemisphere land-cover. It’s the first study to examine how heat wave extent has increased over time on a global scale.

“It means the number of people and ecosystems that are being stressed by the heat wave will grow, if [the heat wave] is occupying a larger area,” said Chris Skinner, a professor of environmental, earth and atmospheric sciences at the University of Massachusetts. Skinner presented his recent results on 12 December at AGU’s Fall Meeting in Washington, D.C.

Elderly, low-income, and heat-sensitive populations are especially vulnerable to health effects from heat waves.

Skinner and his team split up the globe into 50-kilometer by 50-kilometer (31-mile by 31-mile) swaths of land, or “grid cells” to examine climate and weather data every day of the year, from 1980 to 2017.

The researchers defined a heat wave as a region experiencing heat exceeding 90 percent of the historical maximum temperature for each day. The conditions need to persist for at least three days in a row to qualify.

They analyzed 37 years of global NASA climate and weather data to see how the size of heat waves has changed over time. Grid-by-grid, the team investigated how often an area exceeded the maximum temperature threshold for that day.

The team documented when one location went through a heat wave and how often neighboring areas also experienced a heat wave. “At every single location on the Earth we determined every single heat wave that location experienced,” Skinner said. “Then we pooled all those heat waves together and determined what an average sized heat wave is for every single location.”

Repeating this process at a day-by-day scale for the 37-year dataset, the researchers found that on-land heat waves grew in size by 25 percent on average. Over the entire surface of the Northern Hemisphere — ocean and land combined – heat waves size averagely increased by 50 percent.

Skinner likened heat waves to “big domes of heat that are spreading out.” In the real world, this data translates to more areas within a region experiencing heat wave conditions at once. “If D.C. is in a heat wave, then New York might be in one, and Philly might be in one too,” Skinner said.

Surprisingly, the team found the greatest growth in heat wave size happened in the winter months over the 38-year period.

“People can still die as a response to a heat wave in the winter time, even though it’s not as hot as heat waves in the summer,” Skinner said.

These heat events in colder months start to blur the lines between what the definitions of seasons are, says Scott Sheridan, who recently published a paper on heat wave incidence increasing throughout the calendar year. “If you have a very warm spell in March, by the time you get to July, that warm spell in March is probably still cooler than what conditions are like in July,” Sheridan explained.

But for animals and people alike, seasons are important. “if there’s false spring – it tricks a lot of species into blooming early,” Sheridan said. “Then if weather returns to normal, you’re going to have huge economic losses through agriculture in particular.”

The next step in Skinner’s research will be investigating how the size of heat waves will change in the future, and pin-pointing which parts of the world are most vulnerable to these events.

“Heat waves are really dangerous,” Skinner said. “They’re increasing in size and intensity, so we’re going to need to up our efforts to prepare for them in the future.”

Hannah Hagemann is a graduate student at the UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.