23 December 2016

Horse hair can help improve accuracy of climate data

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

Winston lives in the Exmoor Pony Center in England and was one of the ponies from which the researchers took tail hair samples.

Credit: Elisabeth Thompson.

By Yasemin Saplakoglu

In a new study, researchers used horsehair to determine that latitude influences certain climate measurements. The finding could help scientists better understand how to compare climate records from different locations and discover other factors potentially affecting climate data, according to the study’s authors.

Scientists have used elephant hair, mummy teeth and ocean sediments as clues for understanding temperature change across millions of years but few studies have used horsehair to look at Earth’s climate.

“Horses haven’t really been used before in climate studies, but they are extremely accessible and there’s quite a lot of them across the globe,” said Elisabeth Thompson, a doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Their abundance makes horses ideal animals to use for climate studies because they can be found at different latitudes and various environmental conditions, said Thompson, who presented her new research at the 2016 American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

Oxygen can take on a few different forms in nature. In the 1960s, researchers began to study these different forms of oxygen to reveal patterns of rainfall and temperature change. Water molecules containing a lighter form of oxygen evaporate quicker than those with a heavier form. For example, there tends to be a greater abundance of light oxygen in glaciers and higher amounts of heavy oxygen in the ocean. In colder temperatures, there is an even greater difference.

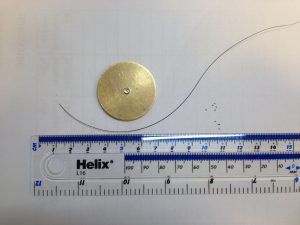

A millimeter size piece of hair is put into a silver capsule for the mass spectrometer.

Credit: Elisabeth Thompson.

In animal objects like horse hair, other factors can affect the accuracy of these measurements. Latitude, or how far north or south the animal lives, can impact climate, according to Thompson. The higher north, the colder the temperature would be, which should be taken into account in climate measurements, she said.

“By studying the oxygen content in modern animals such as horses we can reduce the uncertainty of factors that can affect oxygen isotope ratios,” said Thompson. “Then we can provide more accurate climate information.”

In the new study, Thompson and her team took horse tail hair samples from 24 horses at grooming centers in Shetland, United Kingdom; Selfoss, Iceland; Exmoor, England; and Oxfordshire, England. The researchers chose these locations because of their differences in latitude. Iceland is about 640 miles northwest from Shetland which is in turn farther north than England.

Using a mass spectrometer, Thompson and her team determined the oxygen isotope ratios for the different pieces of hair.

They found evidence to support the hypothesis that latitude impacts oxygen ratios. They found that hair taken from horses higher up in the globe, had a lower oxygen isotope ratio, or more of the lighter form of oxygen.

The reason why latitude affects the oxygen isotope ratio is still unclear, but it is most likely due to differences in temperature or rainfall, according to Thompson. Heavier oxygen falls out of the clouds more quickly in the form of precipitation, leaving behind a higher level of lighter oxygen. Atmospheric circulation patterns then circulate the lighter oxygen in the clouds to higher latitudes, said Thompson. In Iceland, for example, the horses’ hair captured higher amounts of lighter oxygen than in areas in England.

Thompson plans on taking more samples to support this preliminary data.

“It’s a nice method because you can compare the data with oxygen isotope records that we already have,” said Scott Karduck a geologist at Pennsylvania State University in State College who was not part of the study. “It’s also a good way to get a modern and continuous record of changing climate.”

—Yasemin Saplakoglu is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz. Follow her on twitter at @yasemin_sap.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.