10 April 2015

The surprising strength of ‘rainpower’

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Larry O’Hanlon

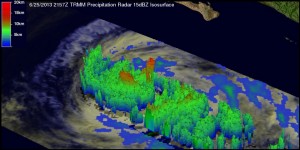

TRMM’s 3-D Precipitation Radar data shows the heavy rainfall in the ragged eyewall of Pacific Hurricane Cosme on June 25, 2013. Data like this, but for the Atlantic Ocean, was critical for measuring rainpower. A new study finds that rainpower in a hurricane can cause winds to decrease by as much as 30 percent.

Credit: NASA

Torrential rains inside hurricanes might be acting as a control knob on these giant storms, reducing their intensity by as much as 30 percent, according to a new study.

In a hurricane, heavy rain falls in the circular wall of clouds that tear around the calm eyes of the storm, “almost like a large river falling out of the sky,” said Pinaki Chakraborty, a fluid mechanics researcher at Okinawa Graduate University in Japan and a co-author of the new study. As the rain falls, the drag, or friction, with the air transfers energy to the air. Chakraborty and his colleagues call the rate of this energy “rainpower”

The new study finds that inside a hurricane, that tiny amount of friction is multiplied by a gigantic number of raindrops and creates enough power to alter the intensity of cyclonic winds. The study’s authors found that instead of being a tiny fraction of the total power of a storm, as scientists previously thought, rainpower in a hurricane is equal to about 15 percent of a storm’s biggest power source: the steamy ocean waters beneath the hurricane.

This rainpower effect causes hurricane winds to decline by 10 to 30 percent, according to the new research published online in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

That makes rainpower large enough to affect models designed to forecast what a hurricane might do next, according to the study’s authors.

Rainpower is not currently included in hurricane models because scientists assumed its effect was small and it would have taken a lot of additional computer power to account for it, said Chris Landsea, a lead hurricane researcher at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center in Miami, who was not involved in the new research.

“The authors (of this paper) find, however, that the rainpower effect is rather sizable,” Landsea said.

The new findings are based on modeling and rainfall measurements in the eyewalls of hurricanes in the North Atlantic Ocean from 1997 to 2013. The rainfall data comes from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, which has been providing space-based, three-dimensional rainfall information since 1997.

“Despite the fact that even Columbus wrote of great deluges falling from the skies, it wasn’t until the 20th century that we had a quantitative view,” said Chakraborty. A key development in measuring rainfall in hurricanes was the advent of ground-based meteorological radar, which provided the first quantitative view in 1944 far surpassing the capabilities of rain gauges. The next major step happened in 1997 when a meteorological radar was put in a satellite. “This space-based radar provided unprecedented view of rainfall in hurricanes in the middle of the ocean,” Chakraborty said.

The researchers used the rainfall data to calculate the rainpower inside the hurricanes. They then added this rainpower into storm models. They found that rainpower reduced the intensity of storms by up to 30 percent. They also modeled North Atlantic hurricanes back to 1979 and found the model better reflected the storms’ actual peak intensities when rainpower was included.

Preliminary work suggests that including the rainpower effect into standard weather and climate computer models can improve forecasts of hurricane winds, said Landsea.

“The paper represents a potentially important finding that may lead in the future toward better hurricane forecasts,” he said.

– Freelance science journalist Larry O’Hanlon acts as AGU’s blogs manager and social media coordinator.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.