22 December 2014

All warmed up and nowhere to go: The missing El Niño of 2014

Posted by kwheeling

By Nicholas Weiler

Sea surface temperatures for December 17, 2014 show a weak warming of the equatorial Pacific, but so far the resulting climate consequences have been underwhelming.

Credit: NOAA

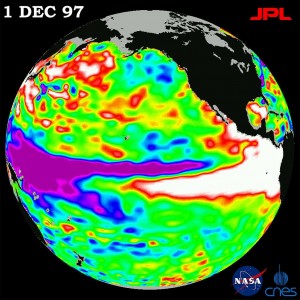

In 1997, a record-breaking El Niño event in the Pacific Ocean brought rain to California, flooding to Peru, and drought to Africa. Earlier this year scientists said that warm currents in the Pacific Ocean presaged the biggest El Niño event since the record-breaking 1997-1998 season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration put the likelihood of a major Northern Hemisphere El Niño at 80 percent.

But despite high expectations, the predicted El Niño of 2014 has ultimately fizzled. In a talk entitled “Who Killed the 2014 El Niño?” at the American Geophysical Union conference Thursday, NOAA oceanographer and past president of AGU Michael McPhaden laid out the leading suspects in this climatic whodunnit – including weak westerly winds, contrary trends elsewhere in the ocean, and overall climate-related ocean warming.

El Niño is the warm phase of a two- to seven-yearlong weather cycle driven by conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Normally, a huge pool of warm water circulates in the western Pacific, off the coast of Papua New Guinea. When Pacific weather conditions shift, replacing easterly trade winds with strong westerly gusts, this warm pool of water gets blown east across the Pacific, catapulting massive storm systems towards the west coast of the Americas.

In early 2014, ocean scientists noted a buildup of warm water in the eastern Pacific, and over the summer the trade winds seemed to weaken, letting through westerly gusts and seeming to set up prime conditions for a major El Niño event as big as the one in 1997.

“This is what excited everyone’s attention,” McPhaden said. “Many interpreted this as onset of another monster El Niño.” Plus, there hadn’t been a really strong El Niño for more than 15 years, he said. “We were due.”

Similar initial ocean conditions in 1997 produced a massive El Niño system that produced extreme weather around the globe.

Credit: NASA

But in subsequent months, the weather anomaly turned out to be pretty wimpy, McPhaden said.

“The heat content was there, ready to be discharged,” he said. But for one reason or another, “the atmosphere just didn’t pay attention.”

In his talk, McPhaden laid out the leading culprits behind the apparent death of the 2014 El Niño.

First, westerly winds didn’t give the warm pool of water in the western Pacific a big enough push. After the first doughty drafts earlier this year, the westerlies faltered and became too weak to drive enough warm water into central pacific to set off real climate fireworks, McPhaden said.

Second, the triggers for El Niño arose at the same time as other ocean trends that may have locked warm waters into the western Pacific and short circuited a big El Niño. These potential culprits include the cool phase of the Pacific’s normal temperature swings, cooling in the eastern Indian Ocean, and the appearance of a type of slow ocean wave that typically signals the end of an El Niño.

Finally, McPhaden said, the pool of warm water in the western Pacific has been expanding over the past 50 years as a result of climate change. As the ocean warms, it may become increasingly difficult for even the strongest westerly winds to move this massive pool of water enough trigger an El Niño. If this is the case, McPhaden told GeoSpace, the Pacific may have become a fundamentally more stable place, and we may see fewer El Niños in the future.

McPhaden said there’s still a huge amount of uncertainty in efforts to predict events like El Niño, and said this is something that ocean and atmospheric scientists need to keep in mind to avoid future false alarms. “The climate system is chaotic,” he said, and scientists’ ability to predict it is still imperfect.

“Whether it was one (factor) acting alone or all in conspiracy,” McPhaden said in his talk, “a large segment of our community was fooled.”

-Nicholas Weiler is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.