30 May 2014

Sonar could spot oil spills hidden by Arctic ice

Posted by abranscombe

By Alexandra Branscombe

WASHINGTON, DC –Melting summer sea ice is opening up new shipping and drilling opportunities in the Arctic, bringing with them the potential for oil spills that could become trapped under the remaining sea ice and go unseen by current oil-detection methods.

Now, a team of scientists is investigating a way to use sound waves to find this elusive oil. Scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts have demonstrated in the laboratory that an underwater sonar system emitting high-frequency sound waves can pinpoint where the oil is beneath the ice, said Christopher Bassett, a post-doctoral scholar at WHOI

As new Arctic shipping opportunities open amid the decreasing sea ice, there is also an increased risk of oil spills that could become trapped under the remaining ice. Scientists are developing an oil-detecting method that uses sonar to find these unseen spills.

Credit: Flickr/USGS

Typical methods for detecting oil spills from the air or at the surface won’t work for finding oil trapped below sea ice because the ice hides oil from searchers, noted Bassett, who described recent experiments at the Acoustical Society of America meeting in Providence, Rhode Island on May 7.

The sonar system sends sound waves undetectable to human and most animal ears up through the ocean. It can detect if oil is present in the water column based on the echo that returns to the detector.

Bassett said that the group plans to submit their first research paper on the new technique soon, and will continue to develop the technology in the laboratory before testing it out in the field. “These results are from a really controlled environment and nature is more complicated, but it is a good first step in that direction,” he said.

Shipping companies are already starting to take advantage of the ice-free Arctic summers caused by climate change. Shipping along the Northern Sea Route above Russia and Northern Europe will grow as more ice in the region melts due to global warming, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In 2013, 71 vessels passed through the route, compared to 46 vessels that used it in 2012, according to the Northern Sea Route Information Office. The IPCC estimates that the route will have up to four ice free-months per year by 2050, compared to barely two ice-free months today, making it easier for more ships to pass through the region, and for companies to take advantage of oil and gas reserves on land and in the sea.

As shipping and oil and gas activities increase, there’s a greater likelihood that an oil spill will occur in this once remote region of the world, and the remaining sea ice could make it difficult to detect these spills, Bassett said.

In the team’s experiments, which took place in a water tank in a laboratory in Hamburg, Germany, the researchers put oil under 12 centimeters (almost 5 inches) of ice that had formed on the surface of the water.

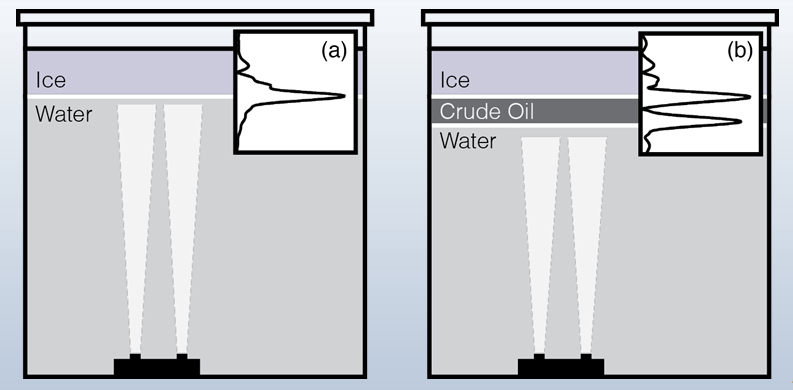

In a laboratory experiment, researchers have detected oil trapped beneath ice by looking for a change in returning sound waves after a signal is emitted from a transmitter (shown at the bottom of each image). The oil layer changes the signal to a double echo, which is picked up by a receiver (next to the transmitter), and appears on a graph (insets (a) and (b)) indicating the spill location.

Credit: Christopher Bassett

The sonar system, which uses a cylinder-shaped signal transmitter about the size of a wine bottle cork, was placed at the bottom of the tank, and sent high-frequency signals up into the water. The signals traveled outward and scattered off objects, like the ice and oil, in the tank. The echoes that returned to the system were recorded by a receiver located next to the sonar transmitter.

Bassett explained that the triple layer of water, oil, and ice bounces back a distinct double echo that tells scientists that there is an oil layer between the water and ice. If oil is not present, there will only be a single echo that is picked up by the receiver.

The new approach uses a sonar signal that rises and falls in pitch. “The tone sweeps upward, kind of like sliding your hands across a keyboard, instead of playing only one note,” Bassett explained in an interview following the presentation. Using multiple tones makes it possible to discern thinner layers of oil than a single-tone system could detect, he added.

The laboratory results bode well for using the sonar technique to locate oil trapped under sea ice, said Bassett. After refining the technique, he and his colleagues would like to seek funding to mount a similar system on a robotic underwater vehicle for use in remote areas.

– Alexandra Branscombe is a science writing intern in AGU’s Public Information department

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.