19 April 2013

Exploring a changing coast in the face of sea level rise – Galveston, Texas

Posted by mcadams

By Kristan Uhlenbrock

Two Texas coastal houses located on the former Brazos River Delta are experiencing lack of sediment accumulation and rising seas. Photo by Kristan Uhlenbrock, American Geophysical Union.

Galveston, Texas – Over 80 scientists gathered at a conference here this week to share their latest research on past, current, and projected future sea level rise and to discuss how this information can be used to shape policy. Despite their diverse perspectives and expertise, one thing the scientists agreed on for sure: the rates and impacts of sea level rise are local and communities are facing a growing risk.

Throughout the week, it was emphasized that the rise of sea level is not a smooth line, but is better characterized as having upsurges and pulses happening over different time scales.

“We are seeing the beginning of a new pulse of rapid sea level rise,” said Hal Wanless of the University of Miami, in Coral Gables, Fla., comparing the last interglacial period to today. Over the last century, we have seen a five- to six-fold increase in the rate of sea level rise, he noted, which is more rapid than what had been anticipated.

Scientists explore the Galveston, Texas, seawall built in response to the 1900 storm. Up to about 30 meters (100 feet) of shore used to be present here. Photo by Kristan Uhlenbrock, American Geophysical Union.

To see some examples of sea level rise impacting a community and how different shoreline structures interact, the group took to the road Wednesday (17 April) for a field trip to Galveston and Follets Islands.

The first stop was the former Brazos River Delta, which shifted in 1929 when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers diverted the Brazos River, altering the delta and sediment transport from the river to form a new delta southwest of Freeport, Texas. This river is a major source of sediment to the upper Texas coast. In addition to the engineering diversion, saltwater intrusion in the lower river inhibits sediment export from the river, recent research indicates.

The studies also show that, due to decreased sedimentation, current sediments on the shelf are being carried greater distances away from the mouth. With shorelines in the Galveston area currently receding between 3 and 4 meters (10 and 13 feet) per year and sediment not accumulating, the shifting shoreline and rising seas are impacting, or putting at risk, houses built in the old delta area.

At the turn of the 20th century, one of the deadliest storms in U.S. history hit Galveston, killing over 6,000 people. In response to that disaster, the city built a seawall 5 meters (16 feet) high and 11 kilometers (7 miles) long and raised parts of the city by 1 to 2 meters (about 3 to 6 feet).

At the time the seawall was built, the beach extended about 30 meters (about 100 feet) seaward; however, due to a highly active coastal environment, much of the beach is gone. Within the last century, the shoreline has degraded and the local sea level has risen by about 0.5 meters (1 to 2 feet), reaching the seawall in many places and threatening the infrastructure it was meant to protect.

Galveston is under direct and immediate threat. Rates of sea level rise there, due to human influence, are “unprecedented and unsustainable,” said John Anderson of Rice University, in Houston, Texas, one of the conference organizers.

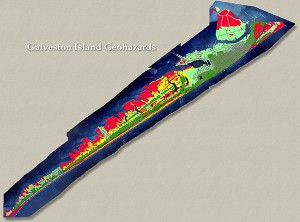

This geohazard map of Galveston Island shows areas of vulnerability on the island. Areas in red are the most at risk to the impact of rising water. Graphic from the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology.

One of the only areas of the island that seems to be holding its own is the east end. This is due to the fact that beaches there have been trapping additional sand from jetties and building up some land. However, the amount of sediment accessible to Galveston Island is not enough to keep up with future sea level rise projections. Engineering of the coasts brings about possibilities for adapting to sea level rise, but also provokes challenges and questions about long-term stability of coastal lands.

-Kristan Uhlenbrock, an oceanographer by training, is a public affairs coordinator at the American Geophysical Union. She is currently attending the Joint Penrose / Chapman Conference on Coastal Processes and Environments Under Sea-Level Rise and Changing Climate: Science to Inform Management in Galveston, Texas.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.