16 December 2010

Saturn’s moonlets play hide-and-seek

Posted by mohi

Everyone knows Saturn has rings. Lots of them. They’re big, easily visible, and have achieved iconic status.

But did you know that hiding within those rings are tiny, tiny moons, some less than a kilometer across?

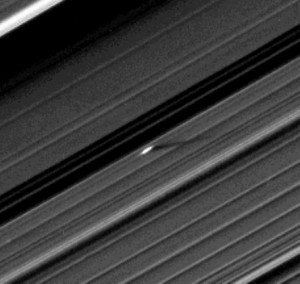

A propeller moon creates a blemish in Saturn's A ring, as imaged by the NASA's Cassini spacecraft. The propeller is 130 kilometers long and casts a 350-kilometer-long shadow.

The moons–or moonlets–are so small they’re invisible even to the Cassini spacecraft buzzing around Saturn. But we know they’re there: we can see the distinctive, propeller-shaped patterns they make in Saturn’s rings as they orbit the planet in pathways subtly distict from the rings in which they travel. Identifying the source of the rings’ blemishes led to the discovery of the tiny, revolving objects.

Saturn’s rings might host hundreds of these moons, just like a tree might hide dozens of tiny birds, visible only when they shake the leaves. Images from the Cassini probe revealed the propeller-shaped moon-prints. Cornell University’s Michael Tiscareno discussed the propeller moons during his talk in Wednesday’s session P33D “Planetary Rings: Theory and Observation II.”

Tiscareno studies the larger of these moonlets–the “giant propellers” in the distant reaches of Saturn’s outer ring, called the “A ring.” Worth noting is that swarms of tinier satellites have been identified in that same ring, but closer to the planet, in what Tiscareno terms the “propeller belt region.” But those swarming moonlets are too clumped to study individually, forcing Tiscareno to focus on the more distant, widely-spaced “giant” moonlets.

One propeller, named “Bleriot” after the French aviator, is “the largest and the most interesting,” Tiscareno said. He’s seen this moon–or its dusty wake–more than 100 times, and has been able to follow its orbit around the giant planet.

“This is the first time that any object has had its orbit tracked that is not orbiting in empty space,” Tiscareno said. “We know of 300+ moons in the solar system and every single one of them was orbiting in empty space until now. These objects are embedded in a disk and yet we’re still able to track their orbits.”

When scientists followed Bleriot through its ringed highway, they found irregularities in its orbit – deviations from the expected Keplerian path, which is elliptical. Bleriot’s orbit resembled a weaving, lane-changing aggressive motorist: it migrated inside and outside of its predicted lane, and Tiscareno proposed that interactions with Saturn’s ring were the source of its meandering.

Basically, Bleriot is being kicked around, by gravity or by ring matter. “Kicks can occur if the moonlet has an encounter with a particularly large ring particle or a particularly massive clump,” Tiscareno explained.

Studying these embedded moonlets could help scientists understand how our solar system formed as rings of dust around the Sun coalesced into planets. So these tiny moonlets could, in theory, help answer some of astronomy’s biggest questions.

–Nadia Drake is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

can you please post the name of the author of this blog article. thank you

wow! it just appeared! thank you!