15 December 2010

No scientific ideas were seriously harmed in the making of this film

Posted by mohi

The intrepid, space-traveling astronomer (Contact). The disheveled, hard-working nerdy hero (Independence Day). And the mad scientist fomenting explosions in experimental zeal (Back to the Future).

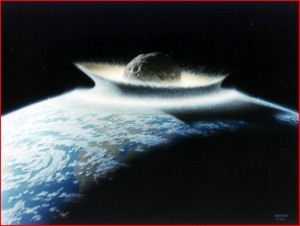

Are Hollywood's depictions of planetary impacts accurate? Does it matter? Image courtesy of NASA/Donald E. Lewis

Hollywood embraces all of these scientific archetypes. But what about the reality behind the characters? What about the science? Does anyone care that the Starship Enterprise wouldn’t really “whoosh” as it passes the camera, that global climate change won’t bring about a new ice age in a matter of days, or that we can’t blow up an asteroid with a hydrogen bomb?

Science in Hollywood was the focus of Tuesday night’s panel discussion, titled “Hollywood Does (Geo) Science.” Emory University’s Sidney Perkowitz moderated, and panelists were Jon Amiel, director of The Core and Creation, Bruce Joel Rubin, screenwriter for Deep Impact, Arvind Singhal from the University of Texas at El Paso, and the SETI Institute’s Seth Shostak.

That cinema–and other forms of entertainment–inspire interest in science was undisputed. “Hollywood science fiction is so widespread that you have to call it a cultural force,” Perkowitz said. Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of the audience indicated that the entertainment industry piqued their scientific curiosity. And, Amiel said he tries to illuminate “the endlessly exciting drama and mystery that’s inherent in all scientific exploration” when he tackles a new, science-driven story.

Panelists agreed that accuracy was important, though it could be sacrificed somewhat to tell a story. Shostak explained that some errors might be made for convenience or out of dramatic necessity–like the Enterprise whooshing by–while others “are just bonkers,” like the expense of mining Unobtainium on Pandora in James Cameron’s Avatar–“It’s completely equivalent to ordering a book from Amazon and paying $60,000 for the shipping,” Shostak said.

Other times, the point isn’t to communicate the nitty-gritty of a concept–global warming, for example–but to introduce it in a compelling way. We want to “plant a tiny seed of curiosity in the viewers,” Amiel said. Likewise, it might not really matter if Jodie Foster’s character listens to radio signals on headphones, when the broader issue of extraterrestrial intelligence is what drives the story.

“Films can be factually inaccurate and still illuminate a truth that’s far more profound than the fact itself,” Amiel said.

Both Amiel and Rubin described the process of working with scientists to come up with plausible–if dramatized–stories. For “Deep Impact,” where a comet threatens life on Earth, Rubin extensively researched the possibility of impacts by rocky bodies, worked out a potential scenario for deflection, and carefully calculated the results of an impact. He kept finding “more and more extraordinary information,” he said. The presentation included a screening of a climactic 3-minute segment of “Deep Impact,” when enormous tidal waves drown the eastern United States following a comet’s impact in the Atlantic ocean.

When working on “The Core,” Amiel needed to understand a bit about geology. “For the duration of the film, I became completely immersed in deep Earth science and mesmerized by it,” he said. Sure, you have to indulge in the fantasy that a team of scientists can take an elevator to the core. But the fantasy is what makes it fun!

Such fantasy highlights the differences between science for real and science on film. Shostak said “The hero in science is not the character, but the idea”–the individual scientists don’t matter but the truth they discover does. But the hero in moves is, well, the hero.

–Nadia Drake is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

This was such an entertaining forum that I fear that a serious concept raised by Dr. Singhal–that film and TV can modify human behavior, and thus filmmakers have a degree of social responsibility–got short shrift, particularly as it can be in conflict with the other important concept raised at the forum–that the science portrayed in film doesn’t have to be very accurate so long as it inspires the audience in some way (“An Inconvenient Truth” vs. “The Day After Tomorrow” was cited as an example of how the latter film created far more public awareness global climate change).

So what happens, then, when people believe they’ve been educated when they are in fact misinformed? At the this same AGU conference I learned that many survivors of the Oct. 25, 2010 Mentawai Islands tsunami consciously chose not to evacuate coastal areas even though they felt the earthquake because they believed that a tsunami is always preceded by a withdrawal of the sea, which is false. I was again reminded of this common misconception when I saw the clip of the from“Deep Impact” showing a tsunami generated from an asteroid impact, also preceded by a withdrawal of the sea, which is also incorrect for this type of event despite Mr. Rubin’s claims that he carefully researched and calculated the consequences of the impact shown in the film. So on one hand, “Deep Impact” may have successfully raised awareness of the real threat of comets and asteroids striking the earth, but on the other hand this film (like many others that have depicted tsunamis) misled the audience about the details of a natural hazard that they are far more likely to experience.

I’m not suggesting that the victims of the Mentawai Islands tsunami saw “Deep Imapct” and acted accordingly. Rather, it troubles me that, like an urban legend, a common misconception about tsunamis is reinforced by such films even when the filmmakers make an effort to be as accurate as possible. When I perform outreach work I frequently have to correct public misconceptions such as these. I suspect that misconceptions from a more recent spectacular production, “2012” (plus cable “science” show tie-ins) may explain why some folks in Hawaii evacuated to elevations higher than 300 m for a 1-2 meter tsunami forecast.