March 30, 2021

Art and Science on the Easton Glacier: Reflections from the NCGCP 2020 Field Season

Posted by Mauri Pelto

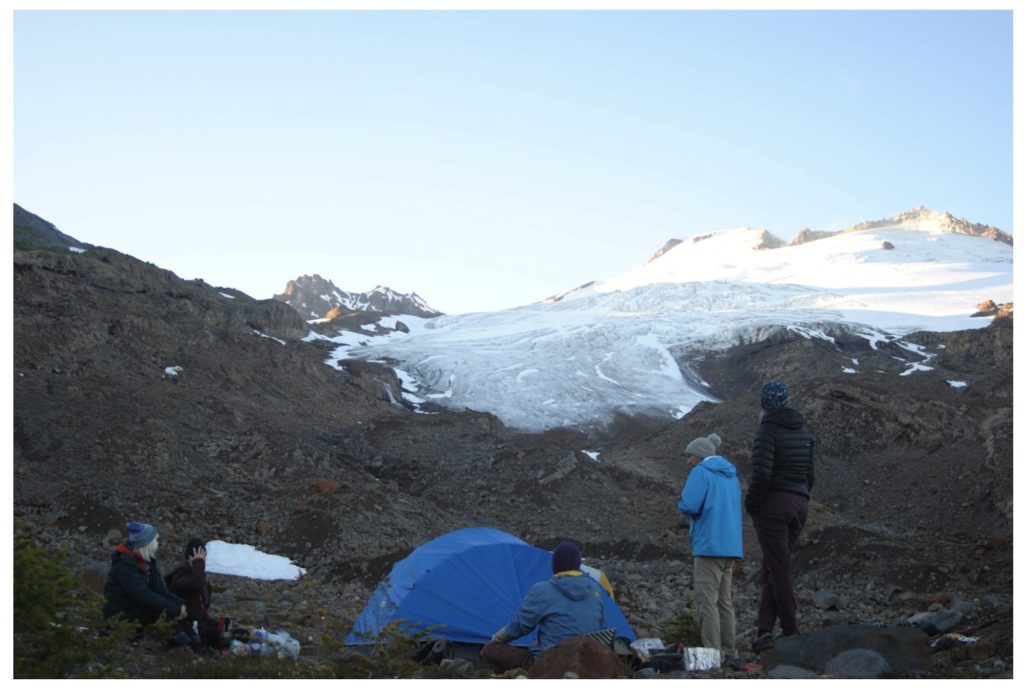

The field team at Camp discussing science communication and gazing at the Easton Glacier. Photo by Jill Pelto

By: Cal Waichler, Jill Pelto, and Mariama Dryak.

It is the evening of Aug. 9th, 2020 and six of us are camped near the terminus of Easton Glacier. The sun has dropped below the moraine ridge above camp and a chilly breeze has forced us to put on layers. We are enjoying dinner cooked on our camp stoves, discussing what we observed on the ice today. The toll of climate change on Easton Glacier, on the southern flank of Mount Baker, is impossible to escape. We are here to both measure this change and communicate what it means.

Within our team of six, four of us are trained as scientists, and all of us highly value creative science communication. This passion can manifest as art (painting, printmaking, sketching), writing, podcasting, blogging or video-making. We all appreciate that exercising creativity with others can provide us with a unique context for communicating about glaciers and climate change.

Cal creates at Columbia Glacier–sketching and taking notes to capture the power of our lunch spot that day. Photo by Mariama Dryak.

The Easton Glacier is large and stretches up to 2950 m elevation. We are here to monitor its health for the 31st consecutive year: its snow coverage, snow depth, terminus retreat, change in surface profile, and its annual mass balance (snow gain vs. snow loss). Easton Glacier is one of the forty-two World Glacier Monitoring Service reference glaciers, meaning it has 30+ consecutive year of mass balance observations, qualifying it for this select group. To learn more about this glacier over time, check out https://glaciers.nichols.edu/easton/ and a previous Easton Glacier update.

While we are at Easton Glacier to measure annual changes, we also see this landscape in the realm of both art and science. From the artistic lens we may note the same things that we do during research: the debris covering the retreating terminus, the crevasses melting down and getting shallower. But we also notice the beauty of these structures, how the crevasse patterns splay out across a knob, and the parallel lines preserved on a serac – recording five years of accumulation like rings on a tree. Observation is a theme in both art and science. We train our eyes to notice things in different ways, to pay attention to certain details. We are able to document these changes in our field notebooks, but also in sketchbooks, journals, photos, and videos.

The records of beauty stored in our sketchbooks serve as a qualitative reminder of what this landscape looks and feels like. In the process of depicting the landscape at the end of a field day, we paint our joy and exhaustion onto the page. In the moment, this act uncovers more details and allows us to reflect. Weeks later when we are off the mountain, we reopen our water-logged, dirt-streaked pages and are taken back to that place where we were. Field sketches, poems and paintings help us capture the emotion of moving through and attempting to understand sublime spaces. They are a vital link between our memories and sharing the meaning of our experience with others. They are also a deliberate recording of time and place — a kind of data in their own right.

The experience of working in this environment is memorable to us — we get to observe a plethora of crevasses, dozens of meltstreams, and strikingly beautiful colors. We can feel a range of excited, inspired, and nervous emotions throughout the day. For us, this experience is giving us the emotional context to our research: being present we can understand that “why”. That reason why the work matters not just for scientific knowledge, or the local ecosystem, but also for humanity. The science results alone can share the data that underlies that, but they might not always connect with other people in a way that elicits that comprehension. Our creative communication through writing and art can elicit that deeper, emotional understanding of why it’s important to preserve and protect these places, and why we need to understand the amount of change that will occur to the climate and ecosystem. Our collection of art shares stories about Easton Glacier in ways that connect with the science, and also go beyond it.

This summer we all felt especially fortunate to be in the North Cascades. Covid-19 has kept us all so isolated and often indoors. The chance to work on the glaciers and live at their feet for two weeks gave us back some of the breathing room we lacked in 2020 – a lucky opportunity indeed.

Cal’s Art – clairewaichler.com

Mariama’s website – Let’s Do Something Big

Jill’s Art – jillpelto.com

- The three forks of the Nooksack River surround Mt. Baker. The North Fork, in blue, receives the most glacier-melt contributions to streamflow. The other branches are less glaciated, and therefore experience warmer water temperatures. In this intaglio print, a photograph of a stream rushing down from the Easton glacier textures the plate. Color, texture and shape are important tools within science communication. Art by Cal Waichler

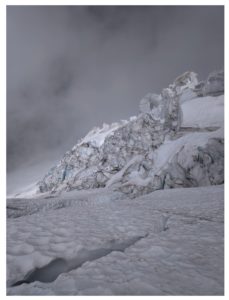

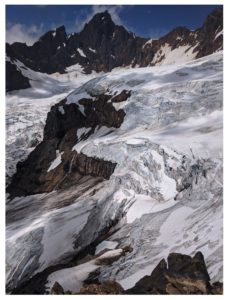

- Icefall on Easton: A striking segment of the icefall inspired art in the form of paintings and words for all of us. Photo by Mariama Dryak

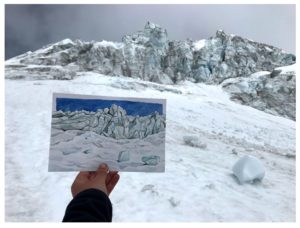

- Taking a short break during a day of glacier measurements to paint one of the large icefalls on the Easton Glacier. When the painting was started, the sky was all blue, but the mountain weather shifted over the hour. Icefalls are ever-changing, and it was unique to paint one up close. Art by Jill Pelto

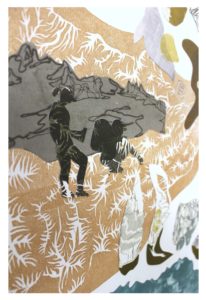

- We stand at the 2020 terminus of the Easton Glacier. Mt Baker looms overhead, intercepting weather systems as they sweep over the Cascades. Meters of snow accumulate yearly on the volcano. Below the summit, the sculpted columns of the Easton Ice Fall fall like pages in a book – lines of dirt and soot distinguishing annual layers. Looking downhill, Railroad Grade moraine hems in a tumultuous series of smaller moraines. The ghosts of Jill and Mauri stand on these piles of rubble far downhill, marking the location where they stood on the glacier 10, 35 years ago, when the tongue of the glacier obscured the rock. In this landscape, we soak in the sounds of rushing snowmelt. The call of the pika is notably absent, but the memory of this small animal’s “eee!” remains. Everywhere we look, there are indications of change. Geology, biology and snow all hold time signatures. Art by Cal Waichler.

- Collaged prints showing the textures, colors and characters of the Easton Glacier. Scientists lower instruments to measure crevasse depth. Art by Cal Waichler

- A full day on the Easton takes the team to striking and inspiring views on the Deming Icefall. Photo by Mariama Dryak

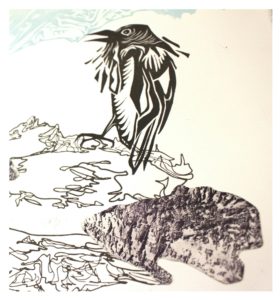

- Collaged print. A raven overlooks the Easton and Deming glaciers. Art by Cal Waichler

- Jill stands where the terminus for Easton Glacier was the first year she joined in the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project twelve years prior to 2020. Photo by Mariama Dryak

Dean of Academic Affairs at Nichols College and Professor of Environmental Science at Nichols College in Massachusetts since 1989. Glaciologist directing the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project since 1984. This project monitors the mass balance and behavior of more glaciers than any other in North America.

Dean of Academic Affairs at Nichols College and Professor of Environmental Science at Nichols College in Massachusetts since 1989. Glaciologist directing the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project since 1984. This project monitors the mass balance and behavior of more glaciers than any other in North America.