25 August 2011

Aftershocks

Posted by Callan Bentley

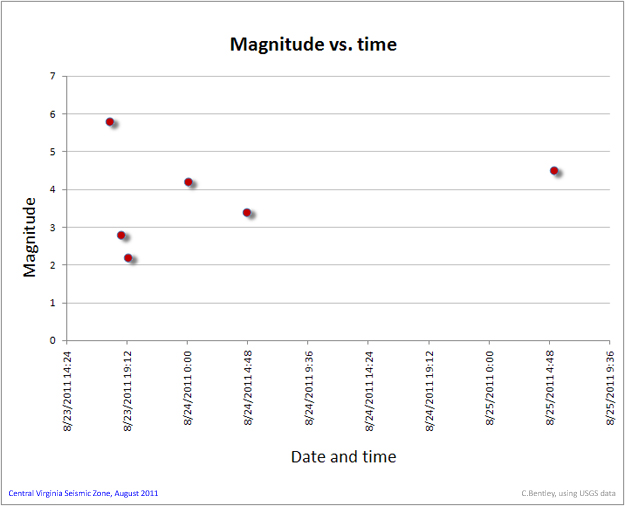

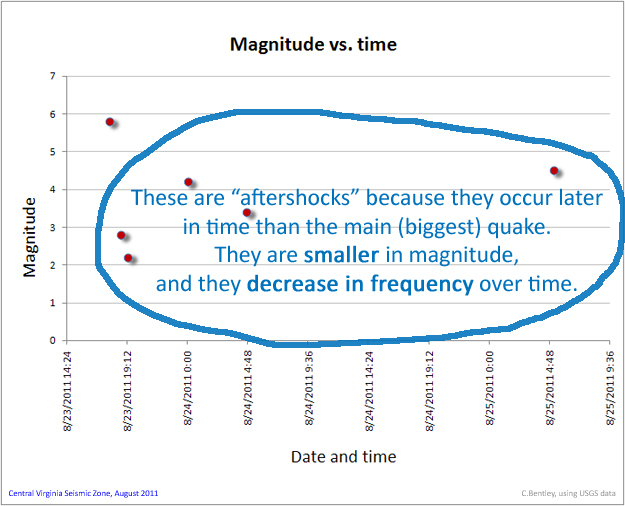

Since Tuesday’s big earthquake, we’ve had 5* aftershocks in the same area (and possibly on the same fault). The most recent one popped off last night at 1am. Here’s a plot showing the size of the events (moment magnitude) relative to the passing of time:

Note that the quakes that came after “the big one” are smaller in their size (the amount of energy that they release into the surrounding rock). We call these “aftershocks” – they are smaller-scale readjustments in the rocks immediately adjacent to the main rupture (including further along on the same fault, potentially) as those rocks shift to come to equilibrium under the newly-modified stress regime.

Notice that the aftershocks are smaller, and they get to be less and less common. Chris Rowan explained this lucidly on Highly Allochthonous in the aftermath of the big Sendai (Tohoku) earthquake in Japan earlier this year. A key point is that while we cannot predict the exact timing or place of any earthquake, including aftershocks, we can make broad, general statements about the way a population of aftershocks looks, given the vantage provided by the passage of time. They decrease in severity and in frequency as time goes by.

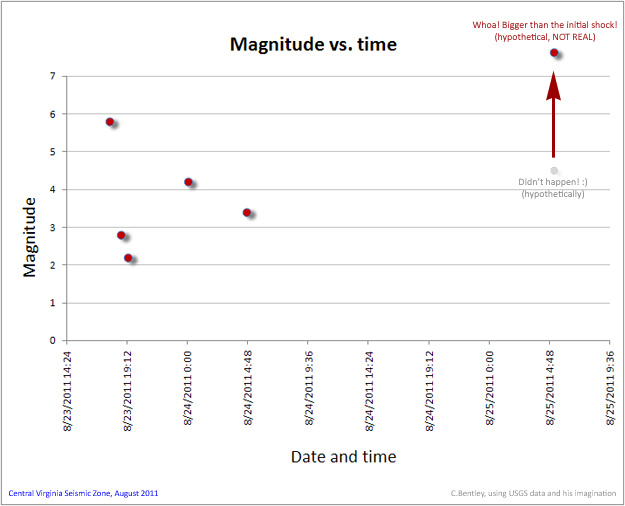

Okay, but what if that wasn’t how things had actually played out? What if we had a slightly different outcome?

What if, at 1am this morning, we didn’t have a 4.5 quake, but instead had a 7.6?

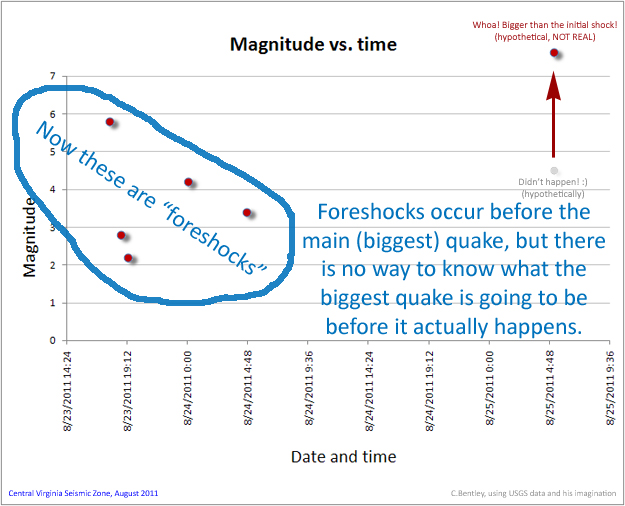

How does this hypothetical scenario change things? In terms of our language, our descriptors for these same events needs to change, given the new information about which quake is really the biggest in the series. We must re-evaluate them in the new context that is provided by this huge event (7.6) that is way bigger than the one (5.8) that started things off on Tuesday. Now Tuesday’s quake and its “aftershocks” are all in the shadow of this much larger event. Their relative position has changed. Though they are the same events, they have been demoted in relative rank.

If my hypothetical scenario were to have played out, the events of Tuesday and Wednesday would now be seen as precursors which loaded additional stress on a more-critically-stressed section of the fault (or an adjacent fault), and so they should be called “foreshocks” instead. Again, there is no way of knowing whether this could be the case until enough time has passed that we can look back and see the pattern of the quakes in aggregate.

Compare these two graphs (one real, one totally fake) to the Japanese quake data that Chris graphed back in March. You’ll see the patterns are broadly similar.

Whether Virginia’s earthquakes this week represent a 5.8 and aftershocks or a series of foreshocks (including a 5.8) leading up to something bigger is impossible to know at this time, while it’s all still playing out. Come back in a year, and it will be more obvious which they were. That being said, Virginia’s tectonic situation is far from any plate boundary, in particular from a subduction zone (where the largest magnitude earthquakes typically occur). So I’m not losing sleep worrying about whether this week’s activity presages some big one, only acknowledging that it is a rational possibility (remember Charleston in 1886, a 7.3 rupture), and that the relevant terminology would change if such a thing were to happen here in Virginia.

________________________________________

* Drat! They just posted another one. Oh, well, I’m not going back to these graphs to update them. Deal with it.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Callan Bentley is Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. For his work on this blog, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers recognized him with the James Shea Award. He has also won the Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council on Higher Education in Virginia, and the Biggs Award for Excellence in Geoscience Teaching from the Geoscience Education Division of the Geological Society of America. In previous years, Callan served as a contributing editor at EARTH magazine, President of the Geological Society of Washington and President the Geo2YC division of NAGT.

Okay, I felt obliged to add the new data to the plot. Here you go:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/59999669@N03/6079988161/in/photostream

Do you have the cumulative strain energy release data for the region? If these data can cover 100yrs period.

Nope. Where would one get that?

Dr. Eric Sandvol,

Department of Geological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA

Callan,

I don’t like the fact it took a seismic event for me to become more interested in the geology of Va ( I live about 30 NNE of the epicenter) but your blogs are top notch, informative and interesting. After going through it and replaying it in my brain many times I now understand why my home moved vertically then horizontally and the shaking associated with it was pretty intense.

You’re adding such a perfect amount of esoterica it makes me want to dive deeper into this.

Really, thanks very much!

Joe,

Thanks for your note. I’m so pleased that it was useful to you!

Callan

[…] last Tuesday we had an earthquake, and we expected some aftershocks as the crust in the Mineral, Virginia, area adjusted to the new stress regime. We expected those […]

Question: say the hypothetical 7.6 occurs. At what time after the original 5.8 (and subsequent aftershocks) would it need to occur to be considered two separate events? Meaning the 5.8 and aftershocks wouldn’t be considered as “foreshocks”. My mind tells me that studies would need to be conducted to see how all the quakes were related but I was curious if there’s an established (or unestablished) time frame they would need to be separated by.

A great question. I’m not familiar with any hard and fast rule, but perhaps a professional seismologist can weigh on that?

[…] more aftershocks, so your humble graphing servant has responded with a plot that updates the images I showed you last week. Here you […]

[…] it bigger by clicking on it. I’ll doubtless have another one to share next week, as more aftershocks occur and are tallied on the USGS […]