23 May 2016

Making the fieldwork count

Posted by Jessica Ball

I’m in the midst of preparing for field work, and it got me to thinking about the public perception of how geologists do research. A lot of us probably extol our chosen profession because of the opportunity for working outside of an office – I know it’s one of the reasons I often bring up when I’m asked why I love volcanology. But I also find that when people follow up with some sort of comment about how nice it must be to do most of my work outside of an office…well, I have to hit them with a caveat. Because in my case, at least, I don’t spend most of my time outside an office.

This may seem a little counter-intuitive when thinking about a largely field-based science. But the reality is that fieldwork takes a lot of logistical preparation and money, and in cases of government employees, sometimes a lot of paperwork to approve. It’s not just a vacation (although a lot of us look on it as a kind of pseudo-vacation – at least we’re away from our desks!) and I think we tend to do a lot less of it than many people think. Now, I’m a modeler, so I probably spend a bit more time in front of my computer than most geologists who don’t work in a lab. But I try to get out into the field as much as I can, so I feel I’m not too far off from the “average”. So what does my time look like?

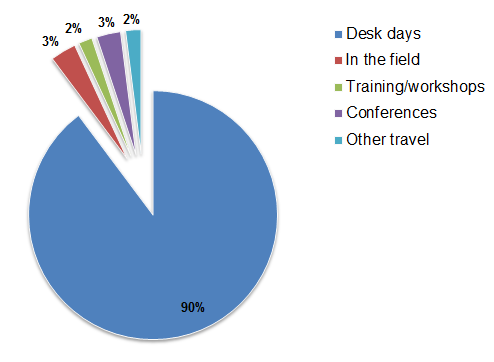

Going back through my calendar for the time that I’ve spent in my current job, let’s say I have about 450 working days, of which 15 are marked as some kind of field trip, 14 as conferences, 8 as training and 9 as some other kind of work-related travel (like meetings or invited talks). When you plug that all into a pie chart, this is what it looks like:

Yikes! I knew I didn’t get out into the field a lot, but I hadn’t realized that even factoring in non-field-related travel, I still spend 90% of my time at a desk. Obviously I’d like to avoid that, because I love getting outside and because it takes me to places like this:

Fortunately next week’s field work will be in Yellowstone National Park, which is as close as you can get to Disneyworld for volcanologists. I’ll be using a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) system to locate and quantify groundwater in a hydrothermally active area (read fumaroles and mudpots). We’ll only be there for 10 days, but the data I will hopefully gather from the site will potentially be enough to write a paper, together with what’s already been done at the site.

And that’s how a lot of geology works. We show off photos and tell stories about our amazing field experiences, but in a lot of cases these trips only take a few weeks or days out of our year. The important thing is that we’ve learned, over the course of our training, to be efficient and thoughtful with our time in the field. We try to gather as much information as possible; we try to collect samples and make observations for questions we might not even have thought to ask yet, because there’s a good chance we might not get to go back (especially if the site is remote and/or difficult to access). When I go to Yellowstone, I’ll be trying to record every possible detail of the trip so I can go back to it later and turn that knowledge into a useful publication.

Going to awesome places is one of the best things about being a geologist, but what we take away from those places in knowledge is just as important, and sustains us through the long hours sitting at a desk!

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.