22 July 2014

Benchmarking Time: DC is all about boundaries

Posted by Jessica Ball

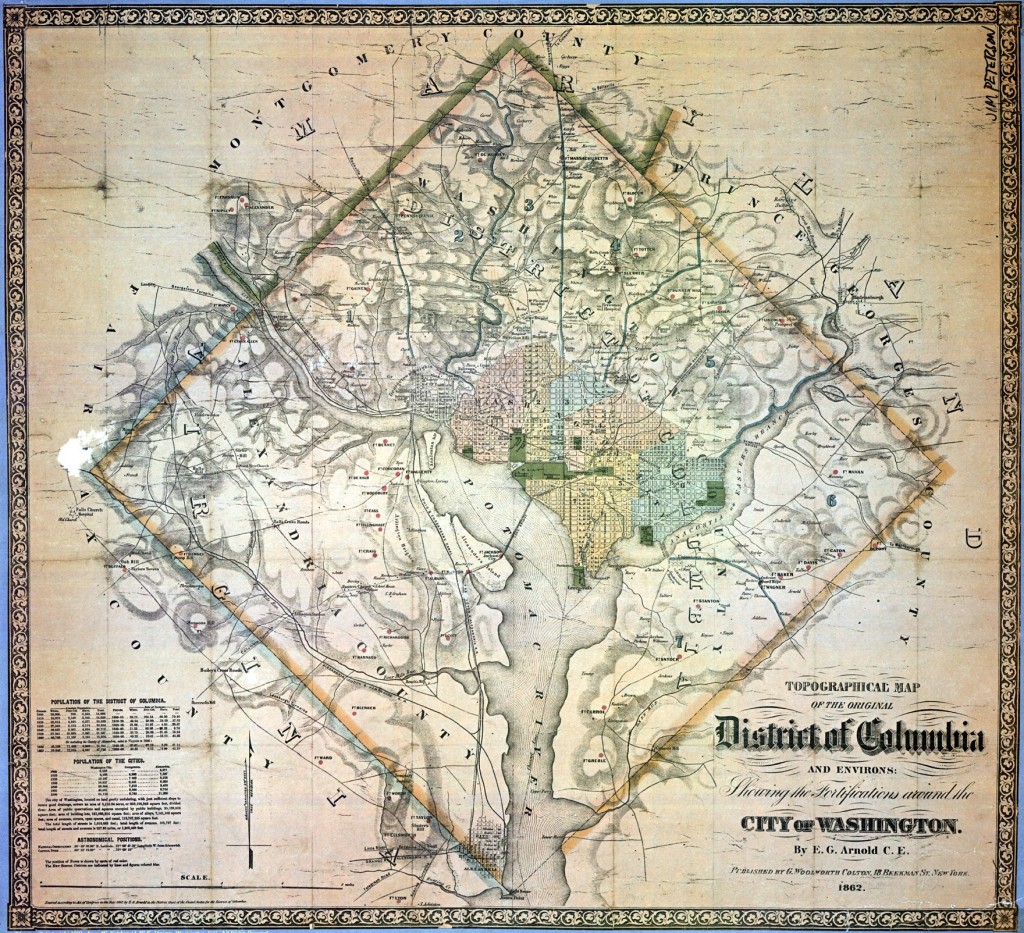

Washington DC is an interesting city. When the original plans were being made in the 1780s and 1790s, they called for a 100-square-mile area to be allocated for the city, and George Washington (who was President at the time) wanted to include the City of Alexandria in Virginia. But the Residence Act, passed in 1791, specified that all the federal buildings had to be on the Maryland side of the river (mostly because someone realized that the law allowed the President to choose the location and some members of Congress didn’t want him taking advantage of that and including his own property to the south of Alexandria). So we ended up with a diamond-shaped District 10 miles on a side, overlapping both Virginia and Maryland, with the actual city in Maryland.

The surveyers began their work at Jones Point, a small peninsula south of Alexandria (click the map to see where it is at the southern tip of the diamond). Jones Point is a neat place even without that distinction; it was a site of Native American occupation for thousands of years, was used for shipping and fishing in the 18th and 19th centuries, and even hosted a shipyard during the first World War. The 19th-century Jones Point Lighthouse is also a neat little building, but what I find most interesting about it is that the seawall it’s built on holds the first boundary stone from the 1791-1792 survey of the District of Columbia

The lighthouse and a bit of the seawall (the official boundary stone, inside the white picket fence, is unfortunately not easy to see). One of the new boundary stones is to the right; since the photo is looking roughly south, this would be the bottom left limb of the diamond.

Even though the boundary stone is hard to see (it’s in a cage topped with a really clouded-up glass cover, so no pictures), you can see the markers that have been put in to delineate the survey lines – there’s one to the right of the photo. And here’s another one, close-up:

A new boundary stone in Jones Point Park – the black bit at the top is part of a metal inlay in the top of the monument indicating the actual boundary line.

But the point of these posts is benchmarks, and like any good survey, this one has a proper federal benchmark as well.

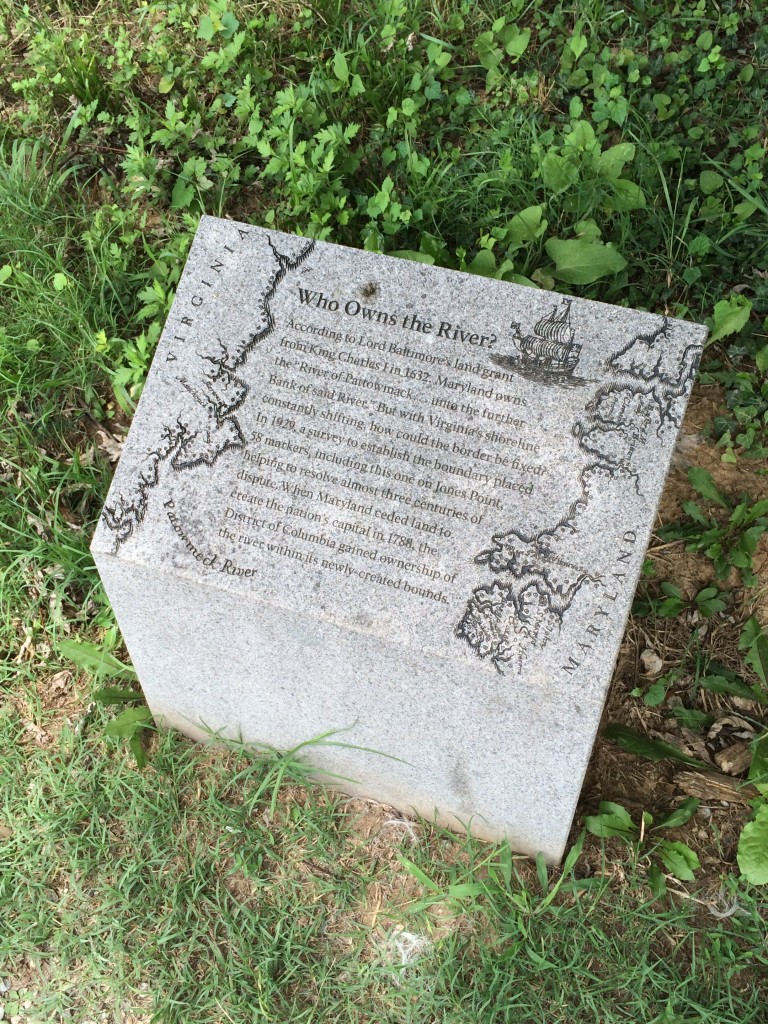

This one is pretty beat-up, but it was put in place by the Virginia-Maryland Boundary Commission in 1929 as part of a survey to resolve the dispute over where the boundaries of Maryland ended and Virginia began; originally Maryland claimed everything including the river, up to the shoreline, but this is a bad way to mark your state boundaries because shorelines shift. (Virginia and Maryland have been fighting for centuries over who owns what in relation to the Potomac River, since at one time shipping and fishing rights were very important and water rights are still a big deal today.) The benchmark was accompanied by a lovely explanatory plaque:

But wait, you say! If this is the edge of the District of Columbia, why is that benchmark only talking about Maryland and Virginia? Well, that’s because from 1840-1846 Virginians lobbied their General Assembly and Congress to approve a retrocession – basically giving back the bit of DC on the Virginia side of the Potomac to Virginia. This happened for a number of reasons: Congress sets the budget for DC and they were financially neglecting the City of Alexandria (this is still a big problem in DC nowadays); the Residence Act had forbidden any federal government buildings from being erected on the Virginia side of the river; and rumors about abolitionist movements in the capital made Alexandria, a major center of slave trade, worried about economic implications. In 1846 the lobbying paid off and Congress passed a law returning all the District’s territory south of the Potomac River back to the Commonwealth of Virginia (although the General Assembly didn’t approve the subsequent referendum until the next year). The 31 square miles donated by Virginia went back to the Commonwealth, leaving DC with 69 square miles of land and a decidedly wonky outline.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.