30 December 2012

I was dreaming of a white Christmas, but geology got in the way

Posted by Jessica Ball

It hasn’t been a very white Christmas where I am right now (northern Virginia), but if you’ve been following my fellow AGU blogger Callan on Twitter, you’ll know that’s not the case in other parts of the state. And it’s definitely not the case back in Buffalo, which has been getting snow from several winter storms recently. That got me thinking about how geology – and topography – conspire to produce precipitation. (I think about this a lot more now that I live in Buffalo, since we tend to get much more snow than where I grew up, and UB has this interesting habit of rarely closing for weather.)

When I was growing up in Northern Virginia (specifically Fairfax County), snow days were always a big event. But as a kid, I knew that even if my neighborhood in the eastern part of the county didn’t get any snow, the western part probably would. This sometimes resulted in school getting canceled for the entire county even if there was no snow on the ground here – because the western part would usually get socked. But it took me a long time to start thinking about why – and the answer’s all in the elevation.

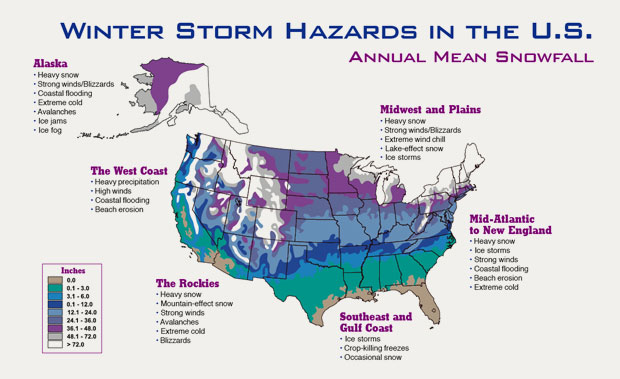

Let’s start with a national look at average annual snowfall amounts:

Note: This is marked as a NOAA graphic, but I haven't been able to find anything on the NOAA site about the dates the info is averaged over or where it came from in the first place. Not even on the NSIDC pages! Come on, NOAA, don't make graphics and then bury them!

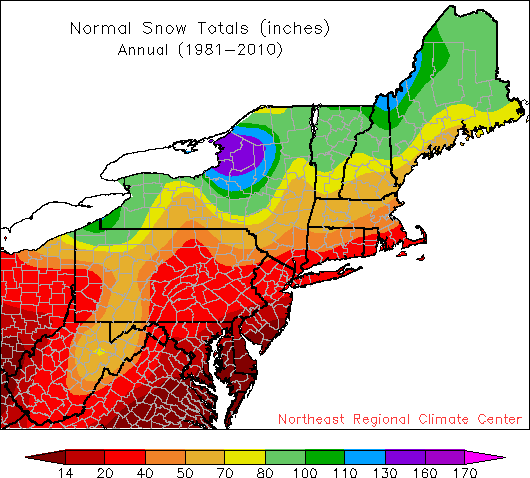

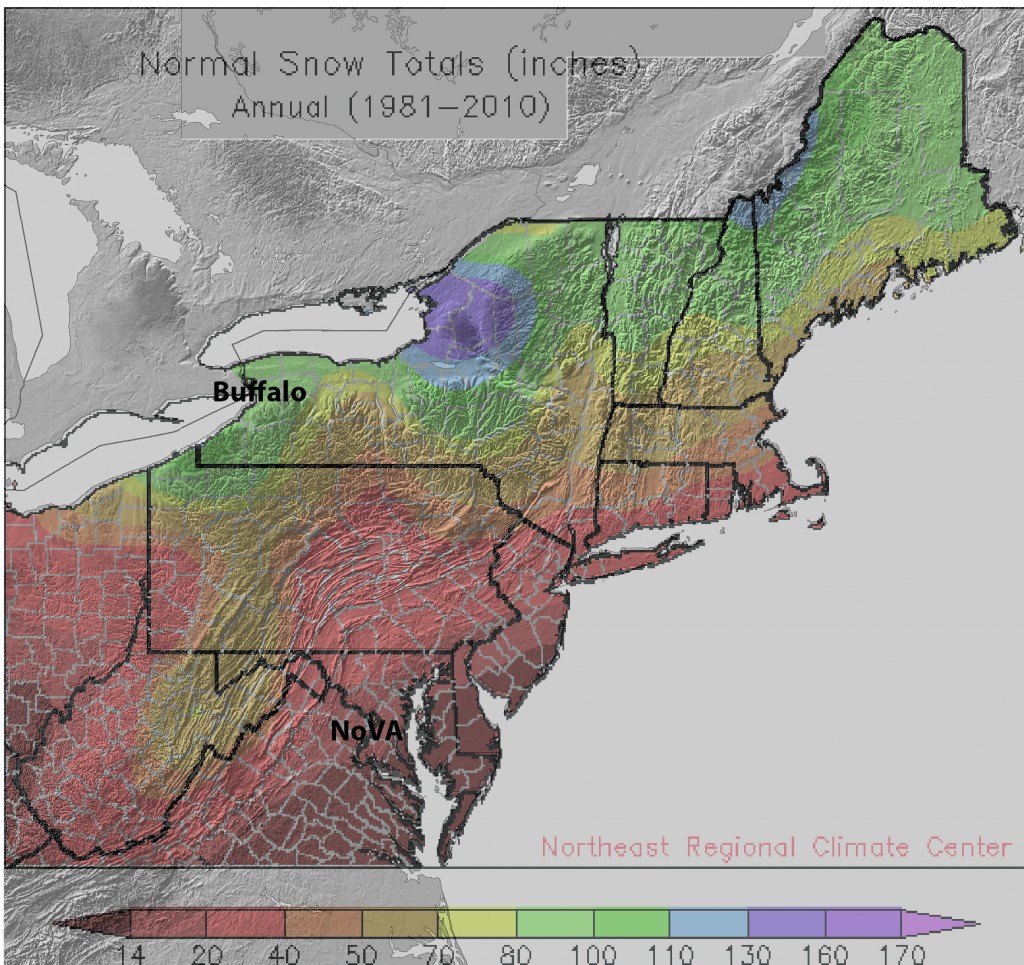

You’ll notice that there are some fairly conspicuous bands of snowfall in the Eastern US, particularly along the borders of the Great Lakes and on a NNE-SSW trend through West Virginia and Pennsylvania. These are the ones I’ll be focusing on. To get a closer look, here’s a regional map of average annual snowfall from 1981-2010 from Cornell’s Northeast Regional Climate Center:

The ‘snow bands” are pretty clear here – a fairly substantial one south of Buffalo along Lake Erie, another at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, and a strip that goes south into Pennsylvania, West Virginia and a bit of Virginia. But snowfall totals don’t tell us much about topography (or geology), so let’s overlay this on a DEM from the National Elevation Dataset:

Now we’ve got something to work with! The disappointing snowfalls of my youth are easily explained by looking at my geographical situation. The bit of Northern Virginia that I’m from is Fairfax County, which covers 407 sq miles, or 1,054 km², and is about 26 miles, or 42 km across. It basically stretches from the Coastal Plain province into the Piedmont, where elevations begin to rise and the topography gets more interesting. Keep heading west and you hit the Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge and Appalachian Plateau, all parts of the Appalachian mountains, where elevations are several thousand feet or more (as opposed to less than 100 feet (30 meters) where I grew up).

This is a prime example of the orographic effect on precipitation – where air masses meeting higher topography are forced to rise (and subsequently cool) to pass over them. This cooling raises the humidity of the air mass and can cause precipitation on the windward side of the topographic high, which in the winter means snow. On the leeward side, the air mass sinks and warms again and either doesn’t precipitate much, or just rains. Since most of the weather in Virginia approaches from the west, this means that when Callan gets snow in the Fort Valley, all I see is rain – or nothing! It also meant that the western part of Fairfax County, which was a few hundred feet higher than the eastern bit, has a much better chance of getting snow (and thus providing snow days for the deprived children of the east).

On to Buffalo. I’ve written before about lake effect snow – Buffalo is right on the edge of Lake Erie, which provides a lot of moisture to weather systems moving in from the west, and thus a lot of snow in the winter (until the lake freezes over). But Buffalo has a rather undeserved reputation for being a snowbound wasteland in the winter, which is actually not the case. Why? Well, it’s because of those lakes – but also because of topography.

The city of Buffalo has an elevation of about 600 feet (180 meters). But go just a bit to the south and Southern Erie, Chautauqua and Catteraugus Counties, and the average elevation goes up to almost 2,000 feet (610 meters) as you move onto the Alleghany Plateau. This is Western NY’s ski country, and with good reason – the higher elevations combine with the lake moisture to create annual snowfalls in the hundreds of inches! Buffalo, which receives moisture from both Lake Erie and Lake Ontario at times, receives about 100 inches or less (and in the case of last year, which was a bit of a bust for snow, we only had about 37 inches). But move into the eastern and northern parts of New York – particularly in the Adirondack Mountains, which have elevations similar to the Blue Ridge in Virginia (between 1,000 and 5,000 feet or 300 and 1,500 meters) – and you start seeing much more snow. Combine high elevations with moisture from Lake Ontario and you’re looking at more than 10 feet of annual snowfall! (In addition, Lake Ontario, which is much deeper than Lake Erie, doesn’t freeze in the winter, so the “snow machine” never shuts down.)

So Buffalo, even though it gets quite a bit more snow than my native Northern Virginia, can hardly compete with the rest of the state when it comes to annual snowfall. In fact, we haven’t won the Golden Snowball Award since 2001 (when there actually was a blizzard). Syracuse has held the record for almost a decade, barring last year, when it went to Rochester (but as I mentioned earlier, last year was a bit of a fluke in terms of winter weather). And the DC area? Despite the occasional significant snowstorm, with an average annual snowfall of little more than a foot, we’re not even in the running.

The upshot of all this is that Northern Virginia has more than a billion years of various orogenies (the Grenville, Taconic [Taconian], Acadian and Alleghanian, to be precise) to thank for its typical lack of snow (in combination with the current orientation of the jet stream). And Buffalo, which just missed being part of the Alleghany Plateau, still ends up with more snow than Virginia because it’s fed by moisture from the Great Lakes, which were shaped by the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet about 10,000 years ago. So in addition to being at the mercy of weather patterns, my white Christmas (or lack thereof) was also, in a sense, predetermined by millions of years worth of geological events. Geology really is destiny!

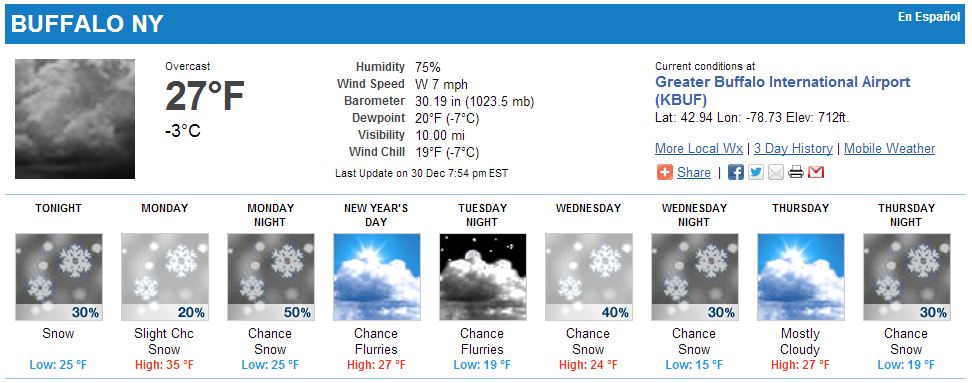

Of course, had I really wanted snow, I could have just stayed in Buffalo over Christmas:

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Jessica Ball is a volcanologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, researching volcanic hydrothermal systems and stability, and doing science communication for the California Volcano Observatory. She previously worked at the Geological Society of America's Washington DC Policy Office, learning about the intersection of Earth science and legislative affairs. Her Mendenhall postdoc and PhD focused on how water affects the stability of volcanoes, and involved both field investigations and numerical modeling applications. Her blogging covers a range of topics, from her experiences in academic geosciences to science outreach and communication to her field and lab work in volcanology.

Sometimes the weather really screws things up. It was my birthday the other day and we planned to have it outdoors but because a storm, I had to cancel the part and I ended up celebrating it on my own, like a dog without a bone.

Thermal profile ( temperatures aloft) )plays a big role in explaining snowfall gradient across Fairfax county. Upper air often oriented SW-NE, with temps and pressure surface falling as you move perpendicular to flow. (SE-NW) think Mount Vernon- Dulles)