9 January 2009

Future British seasonal precipitation extremes – implications for landslides

Posted by Dave Petley

![]() One of the great questions of the age is of course the ways in which climate change will affect the weather patterns that we are likely to see in the future. In the case of landslides the key issue is the ways in which precipitation patterns will alter, especially the most intensive rainfall events that are responsible for many of the most damaging landslides. One of the most significant steps forward over the last few years has been the ability of global climate models to handle these extreme events, meaning that at last we are starting to develop some capability.

One of the great questions of the age is of course the ways in which climate change will affect the weather patterns that we are likely to see in the future. In the case of landslides the key issue is the ways in which precipitation patterns will alter, especially the most intensive rainfall events that are responsible for many of the most damaging landslides. One of the most significant steps forward over the last few years has been the ability of global climate models to handle these extreme events, meaning that at last we are starting to develop some capability.

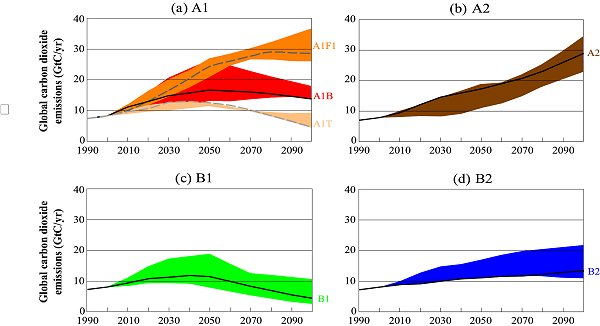

This week an important paper has been published by Fowler and Ekstrom (2009), which seeks to look at the likely changes to very intense rainfall events in the UK. Helen Fowler, is based just up the road from me at Newcastle (the city with the chronically under-performing football team), and her co-author have used modelling ensembles to examine how UK precipitation regimes are likely to change in the time period 2070 to 2100 under the SRES A2 emissions scenario, which is currently effectively our best estimate as to how carbon dioxide emissions will change with time (Fig. 1).

Fig 1: SRES Emissions Scenarios. A2, as used in this study, is shown in Fig. (b). Source: http://www.grida.no/publications/other/ipcc_sr/?src=/Climate/ipcc/emission/014.htm

Fig 1: SRES Emissions Scenarios. A2, as used in this study, is shown in Fig. (b). Source: http://www.grida.no/publications/other/ipcc_sr/?src=/Climate/ipcc/emission/014.htmEnsemble modelling looks at the results of a series of different climate models to examine the range of outputs. Each model operates in a slightly different way, meaning that there will always be a range of results. Therefore, papers presenting ensemble model outcomes always present a range. One of the key issues of interest is whether there is some consistency between them. In this study. Of course the results of such modelling runs are highly complex – in this paper the authors have looked at the 1 day and 10 day precipitation events with a current return period of 25 years. The 1 day event can be thought of as the impact of an intense storm; the 10 day probably simulates a series of low pressure systems tracking across the country, as has happened several times in the last few of years. In landslide terms the 1 day storms might trigger the catastrophic debris flow and sallow failure events, whilst the 10 day events might trigger deeper seated and large slope failures.

First the model is run for the a control period (1961-1990) to check that they can realistically simulate observed conditions. They can. The models are then run to look at what would happen in the period between 2070 and 2100, and the results are then pooled using a fairly interesting approach. Well, the first thing to say is that the Global Climate Models (GCMs) do predict a much warmer climate – global mean temperatures are predicted to be 3.1 to 3.56 degrees warmer than at present. Interestingly though the occurrence of these intense rainfall events also greatly increases for three of the four seasons:

Winter: Increases in occurrence of extreme precipitation of 5 to 30%

Spring: Increases in occurrence of extreme precipitation of 10 to 25%

Summer: Very varied results, with some models suggesting decreases and other increases. More work is needed

Autumn (Fall): Increases in occurrence of extreme precipitation of 5 to 25%

A few of the models do predict larger (and smaller) increases – look at the paper for the full detail. Overall, the authors conclude that “Nevertheless, importantly for policy makers, the multi-model ensembles of change project increases in extreme precipitation for most UK regions in winter, spring and autumn. This change is physically consistent with warmer air in the future climate being able to hold more moisture. The use of multi-day extremes and return periods also showed that short-duration extreme precipitation is projected to increase more than longer-duration extreme precipitation, where the latter is associated with narrower uncertainty ranges.”

The implications for landslides are stark. Increases on this level of the occurrence of extreme precipitation events will inevitably increase the occurrence of slope failures. Therefore, we should expect to see an increase in the occurrence of slope failures. Unfortunately, as landslides are triggered by just a small proportion of our existing rainstorm events, increases in this range are likely to have a disproportionate impact.

Of course the next thing to do will be to build the outputs of these models into slope stability models. This will be a fascinating exercise.

Reference:

H. J. Fowler, M. Ekström (2009). Multi-model ensemble estimates of climate change impacts on UK seasonal precipitation extremes International Journal of Climatology DOI: 10.1002/joc.1827

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

Dave Petley is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull in the United Kingdom. His blog provides commentary and analysis of landslide events occurring worldwide, including the landslides themselves, latest research, and conferences and meetings.

What are the models predicting for cooling change?