9 March 2017

Climate change puts California’s snowpack under the weather

Posted by Lauren Lipuma

New research shows how warming trends affect the Sierra Nevada now and in the future

By Belinda Waymouth

Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak, looking southwest from John Muir Trail/Pacific Crest Trail in the Ansel Adams Wilderness of the Sierra Nevada, California. New research finds the Sierra Nevada snowpack could largely disappear during droughts if greenhouse gas emissions levels aren’t reduced.

Credit: Dcrjsr, Own work, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Skiing in July? It could happen this year, but California’s days of bountiful snow are numbered.

After five years of drought and water restrictions, the state is reeling from its wettest winter in two decades. Moisture-laden storms have turned brown hillsides a lush green and state reservoirs are overflowing. There’s so much snow, Mammoth Mountain resort plans to be open for business on Fourth of July weekend.

But while all that precipitation has put a dent in the current drought — Governor Jerry Brown won’t decide whether to declare it over until the Sierra Nevada snowpack is assessed again in April — new research paints a worrying picture of how drought could affect the snowpack in the future.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack, which provides 60 percent of the state’s water via a vast network of dams and reservoirs, has already been diminished by human-induced climate change and if emissions levels aren’t reduced, the snowpack could largely disappear during droughts, according to a new study accepted for publication today in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“The cryosphere — frozen parts of the planet — has shown the earliest and largest signs of change,” said Alex Hall, a climate scientist at the University of California Los Angeles and co-author of the new study. “The Sierra Nevada are the little piece of the cryosphere that sits right here in California.”

During a drought we see less overall precipitation. Adding in warmer air caused by climate change, a greater share of precipitation falls as rain and snow melts more rapidly. So a frozen resource that gradually melts and recharges reservoirs is particularly vulnerable to a warming climate and droughts that are expected to become increasingly severe.

To protect California’s future from the threat of warming temperatures, California needs to rapidly reconfigure its water storage systems and management practices, according to the study authors.

“I think there are serious questions about the suitability of the current water storage infrastructure as we go forward,” Hall said.

Besides offering a window into the future, the UCLA study revealed some climate effects that are already happening. Hall and co-author Neil Berg found the Sierra Nevada snowpack to be 25 percent below what it would have been without human-induced warming during the 2011 to 2015 drought. The effect was even worse at elevations below 2,400 meters (8,000 feet), where snow cover decreased by up to 43 percent.

“Seeing a reduction of a quarter of the entire snowpack right now — not 20, 30 or 40 years from now — was really surprising,” said Berg, a scientist at RAND Corporation in Arlington, Virginia. “It was almost as if 2015 was the new 2050 in terms of the impacts we were expecting to see.”

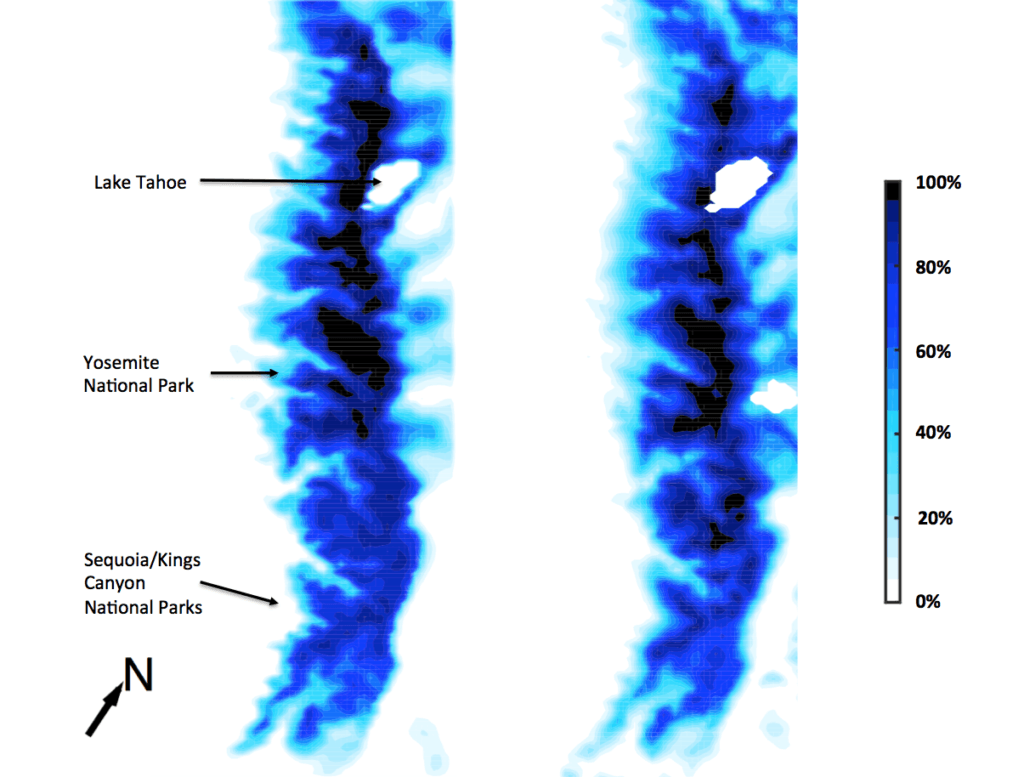

To accurately simulate the drought-altered Sierra snowpack, researchers combined finely calibrated atmospheric, snow and topography modeling. They cross-referenced their results with satellite information and on-the-ground “snow pillows” — devices that measure snow’s water content. They also simulated pre-Industrial Era snowpack, to understand how much human-induced climate change is affecting snow loss now.

Hall and Berg’s computer modeled data (left) closely resembles NOAA satellite imagery of actual Sierra Nevada snowpack (right).

Credit: UCLA.

By the end of the current century, conditions could be even worse, the study found. If humans continue emitting greenhouse gases in a business-as-usual scenario, average temperatures in the Sierras are projected to rise up to 6 degrees Celsius (10 degrees Fahrenheit), causing the snowpack to decrease during drought by a massive 85 percent. There would be almost no snow at altitudes below 2,400 meters (8,000 feet). From a water resources perspective, an 85 percent loss would be as if there was no snow in the Sierras at all, Berg said.

Berg said he found the results sobering. “I feel like I’m walking through a living history book, where we’re seeing these major events unfold right before our eyes.”

Typically, the amount of water accumulated in the snowpack is similar to what reservoirs can store. As things heat up and snow melts earlier, “there’ll be a real storage problem and water will have to be let go,” Hall said.

Hall said he believes the best solution is utilizing groundwater aquifers as a capture and storage mechanism. “The storage potential of groundwater aquifers is enormous; it’s probably 10 times greater than reservoir capacity.”

— Belinda Waymouth is a senior writer at the UCLA Institute of the Environment & Sustainability. Follow her on twitter at @BelindaWaymouth. This post originally appeared as a news story on the UCLA website.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.