13 September 2017

Early volcanic activity may have caused bumps to erupt across lunar plains

Posted by Nanci Bompey

By Patricia Waldron

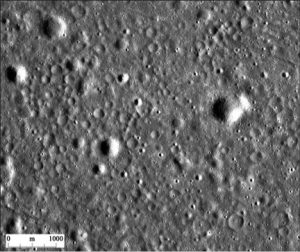

A series of RMDSs in Mare Tranquillitatis, as seen from the relatively low sun illumination images captured by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera.

Credit: Courtesy of Feng Zhang and NASA/GSFC/ASU

Scientists have discovered a new feature on the surface of the Moon: small mounds that grew on its dark plains, likely from volcanic activity.

Researchers at Macau University and colleagues accidentally discovered these mounds while examining high-resolution images of the Moon’s dark patches, called lunar maria. They named them ring-moat dome structures (RMDS) because the bumps are encircled by a moat-like depression.

Once thought to be vast seas, the lunar maria are huge basins that were flooded by dark molten rock during ancient lava flows. They occur primarily on the side of the Moon that faces Earth, creating the face of the “Man in the Moon.”

The researchers believe the newly discovered domes formed in the maria from blobs of foamy magma that bubbled up through cracks in the crust. They describe this process in a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“This discovery was totally by coincidence,” said Feng Zhang, a lunar and planetary scientist at Macau University of Science and Technology in China, and lead author of the new study. “Despite six landings on the Moon and exploration of the surface by Apollo astronauts, as well as years of acquisition of very high-resolution images of the surface of the lunar maria, these enigmatic features remained undetected.”

Zhang came across the bumps while studying images taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is a spacecraft that orbits the Moon capturing high-resolution images, temperature maps and other global data.

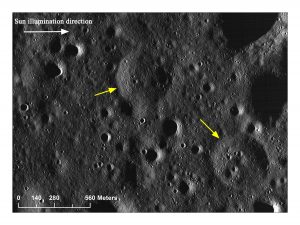

Two RMDSs, indicated with yellow arrows, in Mare Fecunditatis, as seen from the very low sun illumination images captured by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera.

Credit: Courtesy of Feng Zhang and NASA/GSFC/ASU

After consulting with his research group and the literature, Zhang realized the bumps were a previously unknown feature of the Moon. Scientists have observed ring-moat structures on the Moon and other planetary bodies, but none with the same proportions, shapes and numbers that Zhang saw in the LRO images.

The domes may have been overlooked by past Moon exploration missions due to their low height and sparse distribution, and the poor resolution of lunar images that were available before the LRO, said Zhang. The mounds range in size from tens to hundreds of meters in diameter. Most are circular, but some are elongated, with gentle slopes and sunken moats.

The researchers have spotted about 2,000 of the domes across multiple maria, in clusters, as well as individually.

After investigating several possible causes of the domes, the researchers suspect early volcanic activity may be responsible for their formation.

Lava flows formed the maria about 3.2 billion years ago. When this lava began to cool and crack, the liquid rock beneath the crust bubbled up into blobs of magma, called “squeeze ups,” through the fractures. If the magma were foamy and full of water vapor and other volatile gases, then as the squeeze-up cooled, the mass would solidify and sink, creating a moat, according to the new study.

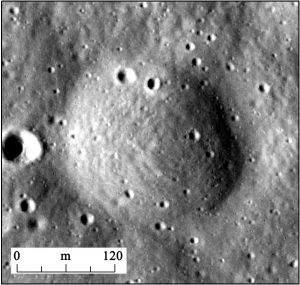

An enlarged view of a RMDS in Mare Tranquillitatis.

Credit: Courtesy of Feng Zhang and NASA/GSFC/ASU.

To learn more about the domes and their provenance, researchers will need higher-resolution images of the Moon’s surface. Such images would reveal certain physical properties, such as whether the domes are cracked across the top, which is characteristic of certain volcanic mounds that form on Earth.

Better images may also clarify the relationship between the domes and lunar craters, which can give hints to a dome’s age. Some domes appear to overlap with a crater, suggesting that the squeeze-up occurred after the impact crater, but it is possible that a landslide of rocky dome material may have filled in a younger crater.

Knowledge of dome formation and weathering may also improve scientists’ understanding of the mechanisms and timing of mare volcanic activity on the Moon, according to the study’s authors.

“There are lots of aspects about the Moon that are still unknown, though we have densely studied the Moon for decades since the Apollo mission era,” Zhang said.

—Patricia Waldron is a freelance writer.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.