18 December 2014

Tracking wastewater in the ocean with satellites

Posted by kwheeling

By Rex Sanders

Scientists can use satellites to track wastewater plumes in the ocean, according to new research presented Tuesday afternoon at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

Researchers from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and other research institutions tracked wastewater plumes from the Los Angeles County and Orange County treatment plants in California during maintenance in 2006 and 2012, respectively. Each plant temporarily diverted wastewater into an older, shorter, shallower pipe. But treated sewage still contains contaminants, so each plant also conducted expensive ocean monitoring.

“We were basically the eyes in the sky. Our job was to try and track these plumes,” said Rebecca Trinh, one of the poster authors and an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley.

Lead author Benjamin Holt, an oceanographer with NASA JPL, and his colleagues analyzed different kinds of data from four satellites: sea surface temperatures; seawater chlorophyll concentrations; and ocean surface roughness, a measure of the slope of ocean waves, which is affected by floating oil and grease. They compared the satellite observations with the monitoring data collected by treatment plant operators in 2006 and 2012.

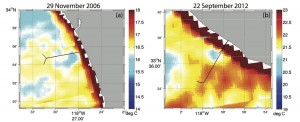

Satellite sea surface temperatures near the Los Angeles County (left) and Orange County (right) wastewater pipes (black lines) in California. Blue patches in the center show lower temperatures for the wastewater plumes near the shorter pipes.

Credit: NASA

The scientists discovered that some kinds of satellite data worked better than others for tracking wastewater plumes. For example, some sensors don’t work at night or when it’s cloudy. And some satellites pass by daily, while others take as long as 35 days to measure the same location.

The temperature and chlorophyll data provided two surprises. Wastewater comes out of the plant several degrees warmer than the ocean, yet the plume showed up cooler on the satellite images.

“What happens is [the warm wastewater] entrains cold deep water and brings it to the surface,”explained Trinh.

And the researchers assumed the nutrient-rich wastewater would increase algae growth. Since algae contain chlorophyll, they expected to see higher chlorophyll concentrations in the ocean. Instead they found less chlorophyll in the plume from the Orange County wastewater plant.

“Even the people on the boats said: ‘Where’s the chlorophyll?'” Trinh said. Orange County had over-chlorinated their wastewater during maintenance, which ultimately killed off some of the algae.

The researchers believe that treatment plant operators could use satellite data to reduce the costs of monitoring future shallow wastewater discharges. And “eyes in the sky” could be used to monitor other ocean discharges worldwide, including storm drains or seasonal rivers after large storms and power plants that use ocean water for cooling, they said.

Video describing satellite tracking of wastewater plumes in the ocean.

Credit: NASA

Rex Sanders is a science communication graduate student at UC Santa Cruz.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.