12 June 2014

Where it burns, it floods: predicting post-fire mudslides in the West

Posted by abranscombe

By Alexandra Branscombe

A mudflow that broke through a containment basin in February 2010, destroyed a this home north of Los Angeles, California, and filled it with boulders, mud, and tree stumps.

Credit: USGS

WASHINGTON, DC – Just a week after a 21,000-acre wildfire between Sedona and Flagstaff, Arizona, residents there are already bracing for mudslides that could surge down the burned slopes. These water-fueled flows of burned-out trees, loose rocks and mud can pack enough power to wipe out homes and roads.

A new online hazard assessment system could help threatened communities in central Arizona and elsewhere in the western United States better contend with the danger of post-fire debris flows.

Shortening the time it takes to get mudslide risk information to residents could minimize injuries and property damage, said Kevin Stewart, who manages the Information Services and Flood Warning Program of the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District (UDFCD), an independent agency in Denver, Colorado. It could also help crews decide where traffic should be diverted when performing road maintenance, he added.

“You aren’t going to completely stop the damage, but if you can get people prepared, then you are 90 percent of the way there,” Stewart said.

The new risk assessment tool, developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and rolled out in Arizona this week, uses a predictive algorithm to calculate the probability of a mudslide after a fire, then displays the regions in a state that are at risk.

A mudflow can form quickly in the years following a fire; if enough rain falls in a burned-out area, the water will rush over the surface and pick up burned rubble like tree stumps and boulders to create a destructive and fast-flowing river.

Credit: Flickr/Dru

A mudslide, or debris flow, is triggered by intense rainfall over an area that has been ravaged by fire, when most or all of the trees and plants have been burned or killed. Because the dead vegetation cannot absorb or slow down the rain, the water starts running quickly over the earth. The growing stream gathers loose soil, rocks, trees and the remains of human structures left behind by wildfires and can quickly become a fast-moving, rubble-filled wall of destruction, explained Jason Kean, a research hydrologist with the USGS Landslide Hazards Program in Golden, Colorado.

“Fires and floods are like peas and carrots,” Stewart said. “[UDFCD] is starting to gear up for a flood even as the fire is getting put out.”

After a large wildfire, USGS assesses the likelihood of mudslides occurring in an area. The rainfall history of an area, soil type, shape of the land, and burn severity, are all incorporated into an algorithm that calculates the probability of a debris flow. A second algorithm estimates the volume of water that could trigger a mudslide, and then how big the mudslide would be. After this probability is calculated, emergency officials rely on rain gauges in the area to see if a storm will dump enough water to trigger a mudslide.

“Our emergency assessments are something we try to get out as soon as possible after a fire,” said Dennis Staley, a research geologist also with the USGS Landslide Hazards Program, who plans to present the online tool at AGU’s Fall Meeting in December. “We help identify which [locations] are the most susceptible to debris flows, and then provide our data to emergency responders, or other people who make decisions.”

In the past, USGS sent out a 12-page hazard report with this information detailing the post-fire risk of a mudslide to first responders and local officials. It can take up to a month to publish and distribute the report, but emergency responders need the information as soon as possible, Kean said.

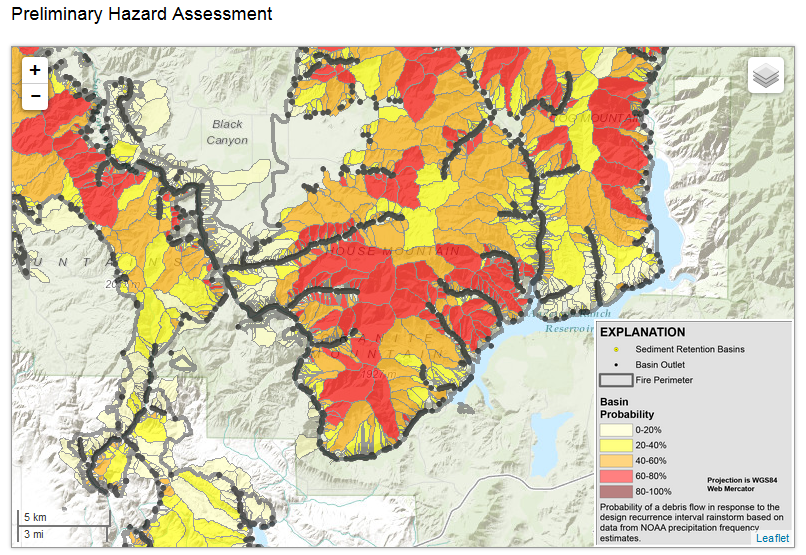

The preliminary hazard assessment for Elmore County, Idaho, after a wildfire burned through the area in 2013 shows which areas (red) are at the most risk of a rain-triggered mudflow. Orange and yellow areas indicate water drainage basins with a moderate risk of a mudflow.

Credit: USGS

The new online tool allows the data from the hazard report to be displayed on an interactive online map that shows the risk of a mud flow with different colors: if an area is white, yellow, or orange, there is a low risk, while red and brown areas carry a high risk of a mudslide. The maps are divided by watersheds, which are areas where water gathers and flows down a slope.

Using the new online system, communities can find out in a matter of days if they are at risk of a post-fire mudslide, if a severe rainstorm comes, Kean said.

“The maps identify what areas are vulnerable or susceptible to a debris flow, and the website prioritizes what basins to worry about,” he said.

Currently, the online hazard assessment is only available for locations in southern California, Idaho, New Mexico and Arizona. USGS aims to provide online debris flow hazard assessments for Colorado and northern California as the fire season progresses.

– Alexandra Branscombe is a science writing intern in AGU’s Public Information department

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.