19 July 2013

Most of Europe’s extreme rains caused by ‘rivers’ in the atmosphere

Posted by mcadams

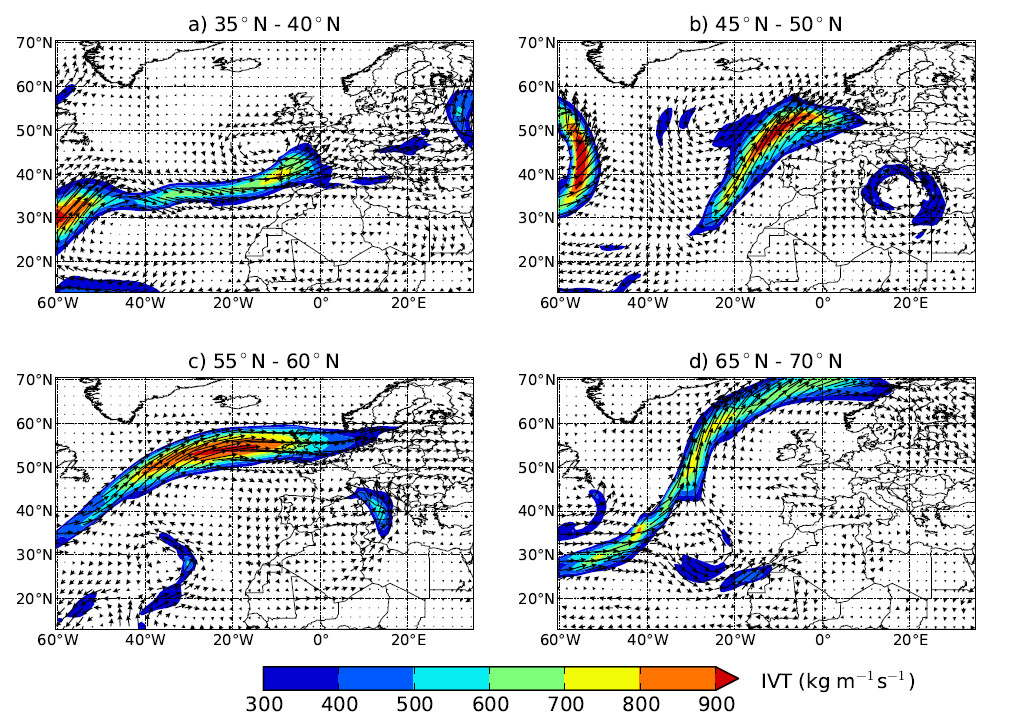

Using their algorithm on historical meteorological data, Lavers and Villarini identified atmospheric rivers at a variety of latitudes by the water vapor they were carrying into Europe — what they call vertically integrated horizontal water vapor transport, or IVT. The four atmospheric rivers shown here each brought heavy rainfall to areas of Europe beneath them on a) May 20, 1994, b) October 27, 1980, c) March 6, 2002 and d) Dec. 1, 1989, respectively. Warmer colors represent more water carried by the river. Photo: American Geophysical Union.

By Larry O’Hanlon

Heavy rainfall brought severe flooding last month to swaths of Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic and other Central European nations, raising water levels in one city to the highest they’ve reached since the 1500s. New research finds that most of the continent’s extreme rainfalls since at least 1979 have spilled from fast flows of warm, moisture-laden air known as atmospheric rivers.

Although the study doesn’t cover the most recent downpours, it concludes that eight out of 10 of the top ten rainfall events in certain parts of Europe between 1979 and 2011 took place when an atmospheric river was flowing into the area.

Identifying these flows of water-rich air offers a way to diagnose the locations that might get affected by heavy precipitation and resultant floods from storms, said David Lavers of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

Lavers is lead author on a paper which was published June 28 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, a publication of the American Geophysical Union. Gabriele Villarini, also of the University of Iowa, coauthored the paper.

Unlike the jet stream, which blows at altitudes of 10 kilometers (6 miles) or so, atmospheric rivers flow through the lower 2.5 kilometers (2 miles) of the atmosphere. Perhaps the most famous atmospheric river is the one which sometimes pours moisture from the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii all the way to the thirsty state of California, and is therefore called the Pineapple Express. Although rivers on the ground follow the same paths for years, atmospheric ones typically flow for just a few days along a particular path; they also come and go as conditions change.

To spot atmospheric rivers that had affected Europe, Lavers and Villarini designed a statistical tool to search through the historic meteorological data, and used it to identify more than 400 instances of atmospheric rivers carrying moisture to Europe from 1979 to 2011. They then looked for matches between those atmospheric rivers and rainfall records throughout Europe.

“What we’ve done is identified all the extreme atmospheric rivers from 1979 to 2011,” said Lavers. These particularly “water-heavy” atmospheric rivers don’t just transport huge amounts of water, but they also change position relatively slowly. So, any given location at the end of the fire hose, so to speak, really gets soaked, Lavers said.

Focusing on the atmospheric rivers as part of weather forecasting—as is already done in California where the water is sorely needed— has provided more specific information about the flooding dangers of a storm in western North America.

Looking at storms in terms of their atmospheric rivers could prove especially important in the future, said Lavers, since the warming atmosphere increases the air’s capacity to hold water, essentially increasing the amount of water that atmospheric rivers can carry, in turn threatening regions with larger floods.

– Larry O’Hanlon is AGU’s social media specialist and manager of the AGU Blogosphere

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.