5 March 2012

Space weather explosions detected on Venus

Posted by kramsayer

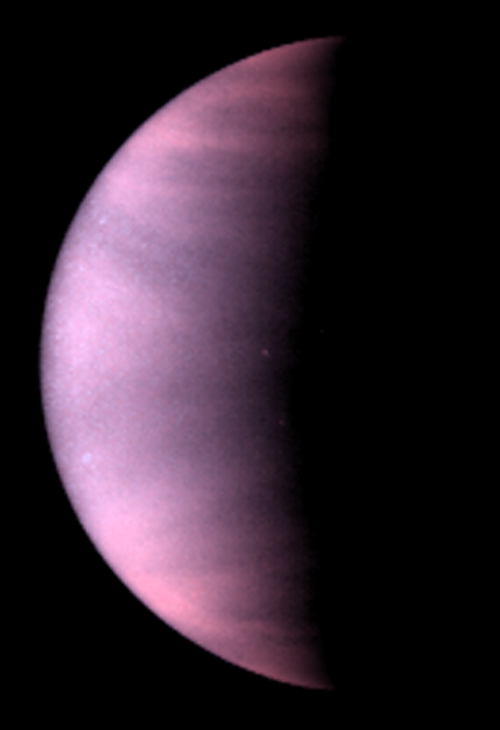

While space weather on Venus is milder than on Earth, a new study shows evidence of explosions on our neighboring planet that can deflect the solar wind. (Credit: NASA)

Author Karen Fox is a science writer specializing in heliophysics at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

In the grand scheme of the solar system, Venus and Earth are almost the same distance from the sun. Yet the planets differ dramatically: Venus is some 100 times hotter than Earth and its days more than 200 times longer. The atmosphere on Venus is so thick that the longest any spacecraft has survived on its surface before being crushed is a little over two hours. There’s another difference, too. Earth has a magnetic field and Venus does not – a crucial distinction when assessing the effects of the sun on each planet.

As the solar wind rushes outward from the sun at nearly a million miles per hour, it is stopped about 44,000 miles away from Earth when it collides with the giant magnetic envelope that surrounds the planet called the magnetosphere. Most of the solar wind flows around the magnetosphere, but in certain circumstances it can enter the magnetosphere to create a variety of dynamic space weather effects on Earth.

Venus has no such protective shield, but it is still an immovable rock surrounded by a sizable atmosphere that disrupts the solar wind and causes interesting space weather effects. With no magnetic field to interact with, space weather at Venus is milder than that at Earth, but occurs much closer to the surface.

A recent study, which will be published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Space Physics, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, has found clear evidence on Venus for a type of space weather quite common at Earth, called a hot flow anomaly. These anomalies, which average one a day near Earth and are also known as HFAs, cause a temporary reversal of the solar wind that normally moves past a planet.

“An HFA explosion causes the material to surges backward,” says David Sibeck, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.,who studies HFAs at Earth and is a co-author on the paper.

“They are an amazing phenomenon,” he adds. “Hot flow anomalies release so much energy that the solar wind is deflected, and can even move back toward the sun. That’s a lot of energy when you consider that the solar wind is supersonic – traveling faster than the speed of sound – and the HFA is strong enough to make it turn around.”

The search for this kind of space weather on Venus began in 2009 when NASA’s Messenger satellite, which is actually a mission to study Mercury, spotted what may well have been an HFA at Venus. But Messenger’s instruments could only measure a suggestive magnetic signature, not detect the temperature of the material inside, a necessary measurement to confirm the heat of a “hot” flow anomaly.

Glyn Collinson, also of Goddard and the first author on the paper, turned to a European Space Agency spacecraft called Venus Express for further evidence. Venus Express was not designed to study space weather phenomena per se, but it does have instruments that can detect magnetic fields and the charged particles, or plasma, that make up the solar wind. Collinson began to search for the telltale signatures of an HFA through a few days’ worth of data.

“That may not sound like much,” he says. “But a day on Venus is 243 Earth days.”

Collinson looked for a pattern of magnetic change that would indicate the spacecraft traveled through one of these gigantic explosions. Given a set of instruments that were not specifically designed to find this signature, the search turned up quite a long list of potential, but not conclusive, events. But his work eventually paid off. A combination of magnetic and plasma data shows that a Venusian hot flow anomaly did indeed take place on March 22, 2008.

“They’ve been seen at Saturn, they may have been seen at Mars, and now we’re seeing them at Venus,” Collinson says. “But at Venus, since there’s no protective magnetic field, the explosion happens right above the surface of the planet.”

Observing an HFA on Venus will help scientists tease out how space weather is similar and different at this planet so foreign to our own. That HFAs can occur on a planet without a magnetic field suggests that they may well happen on planets throughout the solar system, and indeed in other solar systems as well.

–Karen Fox, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center science writer. (For a longer version of this feature, visit NASA’s site.)

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.

GeoSpace is a blog on Earth and space science, managed by AGU’s Public Information staff. The blog features posts by AGU writers and guest contributors on all sorts of relevant science topics, but with a focus on new research and geo and space sciences-related stories that are currently in the news.